When Will Spring Bird Migration Hit Its Peak? BirdCast Has Answers

Spring migration timing varies across the U.S. and even within regions, according to radar data analyzed by BirdCast.

April 5, 2023

From the Spring 2023 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

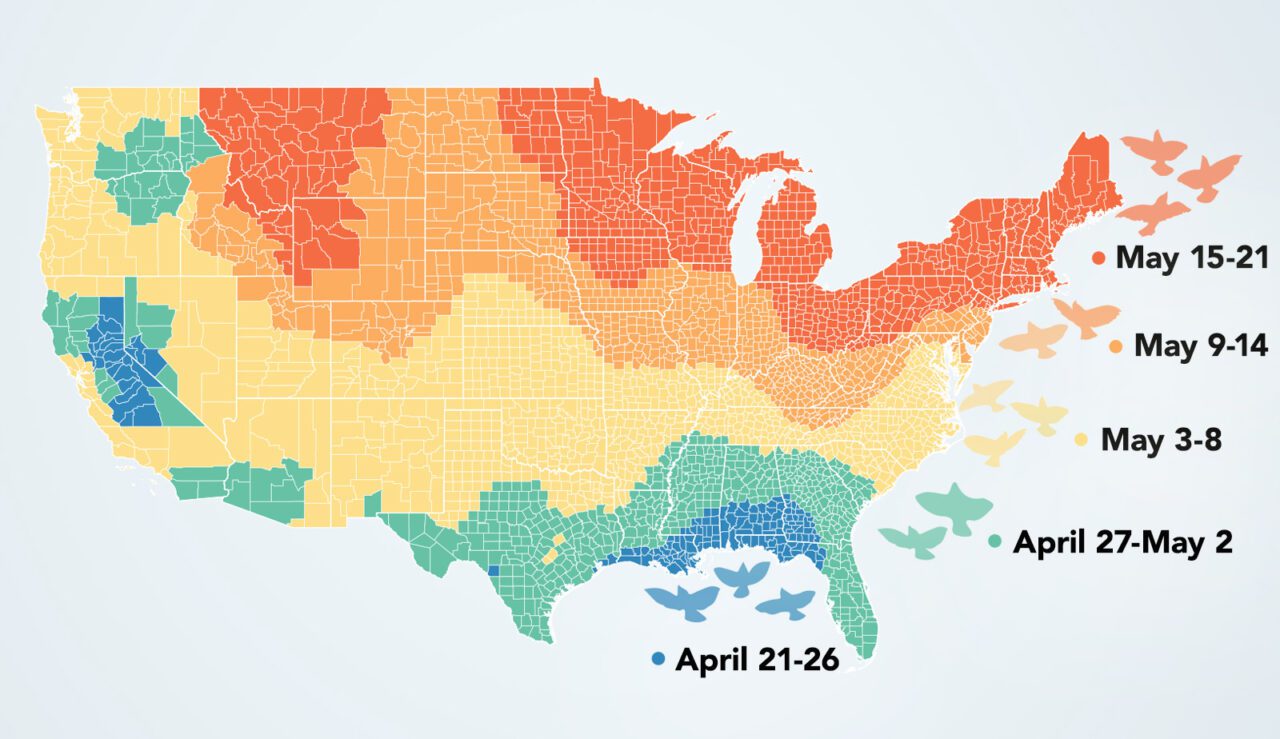

Eager birders in the West will be able to enjoy their peak bird migration bonanza in late April and the first week of May, while birders in the Northeast and Upper Midwest may have to wait a few more weeks, according to a new BirdCast analysis that mapped out the periods of highest aerial bird density across the United States from March to June.

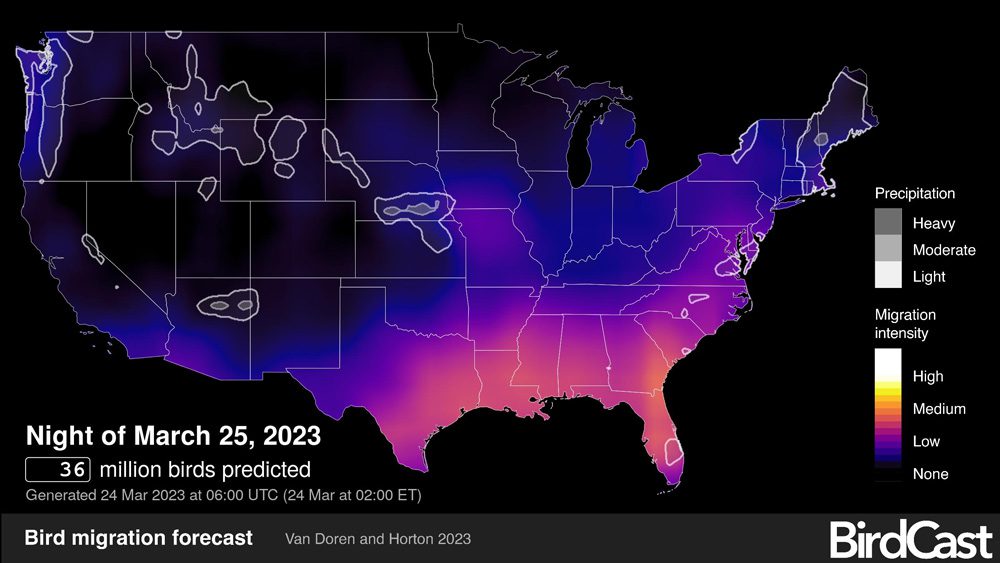

BirdCast is a collaboration among scientists at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Colorado State University, and University of Massachusetts Amherst that uses weather radar and machine learning to track and forecast bird migration. BirdCast has been monitoring nightly bird migration via radar across the U.S. since 1999. This new analysis determined the peak periods of spring bird migration—defined as when the nightly average of birds in the night sky was highest—as measured by 143 radar systems from coast to coast, with each radar measuring aerial bird densities every 10 minutes from 2013 to 2022.

BirdCast senior researcher Adriaan Dokter, a research associate at the Cornell Lab, said differences in bird-migration timing can be seen not just across the continent, but even within some regions.

“One thing that stood out to me is how the western Gulf [of Mexico] and Texas has a later peak migration date than the eastern Gulf,” says Dokter, noting that the difference is driven by the species composition of bird migration in those two areas. “By far the most long-distance migrations [birds such as warblers and orioles that are migrating from overwintering grounds in Central and South America] arrive in the U.S. in the western Gulf states and through Mexico, and way fewer arrive in the East. The Southeast is the main region where lots of common short-distance migrants winter [such as sparrows and blackbirds], and these birds migrate several weeks earlier.”

Dokter notes that the same pattern plays out in California’s Central Valley, where there is an island of overwintering grounds for short-distance migratory birds surrounded by the flight paths of long-distance migratory birds. And he points out that a corridor from western Texas north to the Dakotas registers relatively earlier peak bird-migration periods compared to surrounding areas.

“It’s nice to highlight that [the Great Plains are] a main highway for migration, where birds enter the country, move north, and then distribute west and eastward,” he says.

While weather radar scans can’t be used to identify the bird species on the move—radar just detects the biomass of birds in the air—another project by some of the scientists involved with BirdCast will delve deeper into bird-migration patterns. A study published in the journal Methods in Ecology and Evolution in January, and spearheaded by researchers at UMass Amherst and the Cornell Lab, describes a new machine-learning computer model called BirdFlow that shows exactly which species are specifically going where on migration.

BirdFlow processes multiple data sources—combining weekly estimates of bird numbers from eBird data submitted by birdwatchers with previous studies of birds outfitted with satellite-tracking tags—to accurately predict the movement of particular bird species from location to location, week to week throughout their migrations.

“[With BirdFlow], we’ll be able to unravel the routes that birds take, from their breeding grounds to stopover points to wintering grounds and back— without having to capture birds and attach tracking devices,” says Dokter. “Understanding these connections will be critical to learning why some bird populations are doing poorly and some are doing well.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library