A Single Night of Bird Collisions in Chicago Points to the Need for Window Safety

On the night of Oct. 4, 2023, a massive wave of bird migration swept through Chicago. Nearly 1,000 songbirds died after colliding with just one of the many buildings along the waterfront. But it doesn't have to be so: science shows darkened windows can make a big difference in saving birds.

April 1, 2024

From the Spring 2024 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Chicago experienced a mild autumn in 2023. In September, balmy, warm air blew north into the city, keeping daytime temperatures an average of 2°F degrees warmer than usual. The weather kept southbound migratory songbirds, which don’t like to fly into the wind, in more northern climes, waiting for the winds to shift.

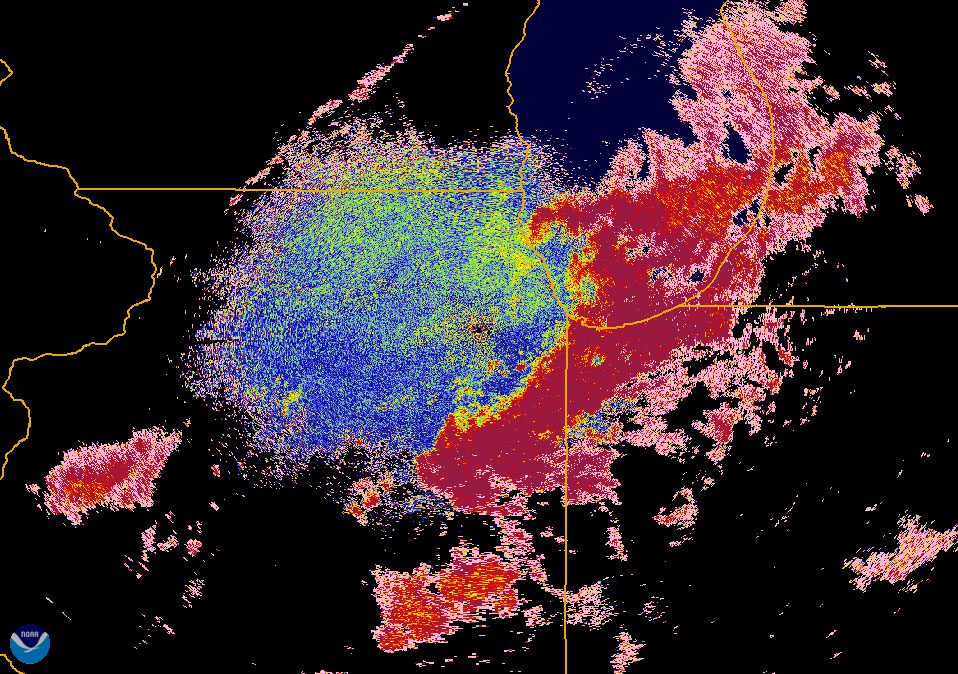

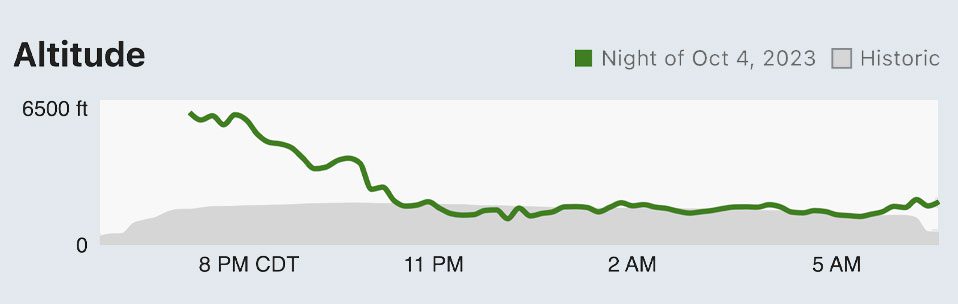

By the beginning of October, there was a huge backup of migratory birds in Wisconsin, according to BirdCast—a collaboration of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Colorado State University, and University of Massachusetts Amherst that uses weather radar and machine learning to track and forecast bird migration.

Then on the night of Oct. 4, the winds changed course, blowing southeast at last—and prompting birds by the tens of thousands to take wing. By 4 a.m., nearly 1.5 million birds were flying above Chicago, according to BirdCast. In the early-morning hours, birdwatchers at Promontory Point, a peninsula that extends into Lake Michigan, were bewildered by the flying masses of birds. The event was “the single most amazing migration spectacle I’ve ever seen,” wrote Marky Mutchler, an ornithology PhD student at the University of Chicago, on X (formerly Twitter).

On her eBird checklist, Mutchler estimated rates in excess of 3,000 birds per minute—with 56 species observed in all, including 16 species of warblers. “In just one hour, we witnessed almost 200,000 migratory birds fly by,” she wrote in the checklist notes. “It will be a long time until I see something like this again!”

Unfortunately, the conditions also resulted in tragedy as thousands of birds crashed into buildings during the night and into the dawn. Redstarts and Soras and buntings slammed into glass structures in record numbers, perhaps seeing only a mirrorlike reflection in the panes—hitting the windows without even knowing they were there.

The unusual weather “caused what we think was a buildup of birds,” says Annette Prince, director of Chicago Bird Collision Monitors, a nonprofit group of volunteers who walk around the city’s skyscrapers looking for, saving, and cataloging the birds that crash into the city’s structures. As usual during migration seasons, Prince woke before dawn on Oct. 5, went downtown, and looked for dead and injured birds. What she and a dozen other volunteers found was disastrous. They usually find close to 7,000 birds in a year. That morning alone the team collected more than 2,000 birds from the city’s sidewalks.

The carnage was worst at McCormick Place, Chicago’s convention center located on Lake Michigan’s shoreline. A 2.6-million-square-foot glass building built in 1960, McCormick Place hosts events throughout the year, like the Chicago Auto Show and this year’s Democratic National Convention. On that October night, workers within the convention center disassembled the setup for one conference and prepared for a health and fitness expo. By morning, nearly 1,000 birds—including more than 300 Palm Warblers, more than 200 Yellow-rumped Warblers, and scores of other warblers, sparrows, and thrushes—lay dead outside, having collided with the glass windows illuminated from within.

Prince says the tragic event that night “highlights the ongoing tragedy of tens of thousands of bird-building collisions that occur every year in the Chicago region.”

What Happened in Chicago the Night of October 4, 2023?

Ornithologists estimate that as many as a billion birds die each year from flying into buildings. They become disoriented by the artificial lights and reflections and slam into glass (see Is Bird Migration Getting More Dangerous? Spring 2021). Shutting off lights during migration and taking other measures, like installing window films on the glass’s exterior, can save birds. A study published in the journal Biological Conservation in 2020 suggested that extinguishing even some light during migration can benefit birds attracted to the artificial radiance. Researchers investigated 48 facades on 13 different buildings in Minneapolis to see which affected birds more: light reflected in glass or artificial light from within a building. Light emitted from inside was the most important factor influencing bird collisions, the researchers found. The result, they said, “provides strong support for turning off lights at night to reduce bird–building collisions.”

Though that research focused on just one urban outpost, other studies have come to similar conclusions. The issue is pervasive, says Benjamin Van Doren, an ornithologist at the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign who studies lights and their effect on birds. “All of the signs, in my opinion, point to this being a really widespread and problematic phenomenon,” he says.

A better understanding of the problem in recent decades—and what building owners can do about it—has led activists and birders to push for lights-out initiatives in cities across the continent. In Toronto, Houston, Dallas, New York City, and many other metropolises, lights-out programs are convincing building owners to shut off their lights at night during migration.

Chicago was one of the first cities to establish a lights-out program, launching its effort in 1995. Participants voluntarily turn off or dim exterior, display, or nonessential lights in their buildings after 11 p.m. during the spring and autumn migration seasons, an effort that helps save tens of thousands of birds every year, according to the city’s website.

The lights-out program is particularly important in Chicago. There, millions of birds migrating through the heart of the country funnel along the expansive Lake Michigan, where they encounter the city’s skyline of 126 skyscrapers—many of them glass. In 2019 a study by Cornell Lab scientists, published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, named Chicago as the most dangerous city for bird migration in the United States, due to a combination of geography and light pollution.

Nearly 100% of Chicago’s downtown multistory buildings are listed as participants in the city’s lights-out program. But according to Prince, some buildings say they participate in light reduction but fail to turn off or obscure their interior lights. McCormick Place is officially in the lights-out program, says Prince, but on nights during exhibitions “they have several football fields of glass windows that pour light out to a darkened lake like a lighthouse onto the ocean.”

The Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority, which owns and operates McCormick Place, says that its lights-out efforts have reduced bird collisions by 80%. MPEA says it enforces a lights-out policy for the building during migration, but only when no staff, visitors, or clients are present.

On the night of Oct. 4, the lights inside stayed bright all night.

The Deadly Cost of Lighted Windows

Nearly 1,000 bird kills were documented at McCormick Place on Oct. 5, 2023, including:

-

335

Palm Warblers

-

182

Yellow-rumped Warblers

-

89

Tennessee Warblers

-

72

Magnolia Warblers

-

55

Common Yellowthroats

-

48

Northern Waterthrushes

-

32

Ovenbirds

-

22

American Redstarts

-

20

Swamp Sparrows

-

20

White-throated Sparrows

-

10

Lincoln’s Sparrows

-

9

Gray Catbirds

-

9

Soras

-

8

Bay-breasted Warblers

-

8

Black-and-white Warblers

-

7

Cape May Warblers

-

6

Swainson’s Thrushes

-

5

Hermit Thrushes

-

4

Gray-cheeked Thrushes

-

36

individuals of 15 other species

Dave Willard of the Field Museum in Chicago has been monitoring bird collisions at the site for more than 40 years. On a typical morning during migration, he might find anywhere from zero up to 15 dead birds. “Rarely does it go into the twenties and thirties,” he says. On that morning he found hundreds. “The most common bird was Palm Warbler,” he says. “To have 300 of one species in one night? Totally unprecedented.”

Illustrations by David Quinn, Tim Worfolk, Ian Lewington, Hilary Burn, and Brian Small, via Birds of the World.

The problem with McCormick Place is not limited to one night.

“Although the October 4 event was calamitous, nearly a thousand birds fly into McCormick Place every year,” says Prince.

Roughly 80% of the birds recovered at the building are dead and 20% are injured. That means that over its 50-year lifetime, McCormick Place has killed tens of thousands of birds.

Migration and Its Hazards

“It doesn’t matter whether it’s 10 a day or 1,000 a day,” she says. “It adds up and the cumulative effect is unacceptable.”

Of all the buildings in Chicago’s downtown, McCormick Place’s effect on birds is perhaps the best studied thanks to Dave Willard, the retired bird collections curator for the Field Museum of Natural History (see The Museum Ornithologist Who Made a Difference in Reducing Bird Kills on Chicago’s Buildings, Spring 2020). One day in the fall of 1978, Willard was curious about whether birds flew into McCormick Place. He walked the mile to the building from the museum and found a few corpses, including a Yellow-billed Cuckoo—enough to keep him coming back.

“I do wonder, had I found nothing on that day, whether I would have had the interest to keep going back,” he says.

In 1982, he and others from the Field Museum began regular surveys during spring and fall migration, documenting the species of birds on the ground, the location of their bodies on a map, and which window bays were illuminated.

In 2021 Willard and Van Doren teamed up to analyze the long-running dataset of bird kills at McCormick Place. Their results, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showed that when half the window area was darkened, bird collisions were 11 times less likely in the spring and 6 times less likely in the fall. Overall, bird collisions could be reduced by 60% if all lights were dimmed, they estimated. In other words, keeping the lights out during migration could save hundreds of birds every year from fatally plowing into windows.

End of Transcript

“We were able to conclusively show that when the window bays were illuminated, the probability of collisions with those specific windows were much, much, much higher than when the lights were turned off,” says Van Doren. “That makes this study, to my knowledge, unique; we’ve been able to really show this causal link.”

Because of the widespread bird-strike problem, architects like Jeanne Gang, who has designed a number of buildings in downtown Chicago, are pioneering new mitigation measures like bird-friendly glass and patterning on a building’s facade. On the 82-story residential Aqua Tower just a few miles north of the convention center, Gang’s design called for fritted glass, which has tiny dots that are easier for birds to see, and deep balconies with railings that create a wave effect to break up window reflections. Prince and the collision monitors are noticing the difference at Aqua Tower. In one season, they found two birds dead from collision there, compared to 60 dead birds at a nearby building.

The benefits to birds are significant when existing buildings are retrofitted with bird-friendly designs, too. For example, the Javits Center—another multi-million-square-foot convention center—was once called the deadliest building for birds in New York City. In 2015, the building underwent a 5-year, $500 million retrofit that included features like fritted glass. Since then, the number of bird deaths there has fallen by 90%, according to New York City Audubon.

Many building owners avoid incorporating bird-friendly design or retrofitting solutions, however—because they say it’s too expensive. But Andrew Farnsworth, a bird-migration expert and visiting scientist at the Cornell Lab, says that bird-safe building solutions such as treated glass are becoming more affordable. And some measures, such as reducing nonessential lighting, actually save money on building energy costs, he says.

“We don’t need more science to tell us there’s a problem and what it is,” says Farnsworth. “We know that, and there are solutions.”

Since the mass bird kill at McCormick Place last October, more than 10,000 bird advocates signed a petition asking Chicago and Illinois state officials to require the MPEA to do more to reduce bird strikes.

MPEA said it will take further measures to protect birds during migration and is looking into using motorized controls to quickly close existing drapery and cover up interior lights. The convention center’s ceilings are 50 feet high, and the blinds currently must be opened and closed manually, which takes multiple workers many hours to do using heavy equipment.

“They should keep their eye on the north side of the building,” says Willard. “A curtain that they already have in place should be drawn for the duration of migration. That allows them to have lights on all night if they need them.”

In December, the MPEA stated that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had provided them with recommendations to minimize bird strikes. A spokesperson for the MPEA, however, did not explain what those recommendations were. The group also said curtains would be drawn overnight during migration going forward, and recently issued a request for proposals for window films and coverings. The group declined to comment further for this article.

“I think that it is a positive step that USFWS has addressed this and hopefully other bird-collision issues,” says Prince. “We would hope for transparency (no pun intended) from the government and MPEA regarding the recommendations or plans to be implemented in order to evaluate that the time, effort, money, and strategies put towards preventing bird collisions at this building’s critical location will prove to be sufficiently effective and worthwhile.”

Prince also says, “We are encouraged that the MPEA is proposing to use glass treatments and coverings at their lakeside facility to prevent bird collisions.”

This spring Dave Willard will continue his surveys at McCormick Place during migration. He plans to start his walks again in March, counting and cataloging as the dawn’s light glints off Chicago’s skyscrapers.

About the Author

Susan Cosier is a Chicago-based freelance journalist who covers science and the environment. Her writing has appeared in Audubon, Scientific American, and The Wall Street Journal.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library