BirdCast Dashboard Spotlights the Hottest States and Counties for Bird Migration

September 22, 2022Originally published in the Autumn 2022 issue of Living Bird magazine. Updated September 2024.

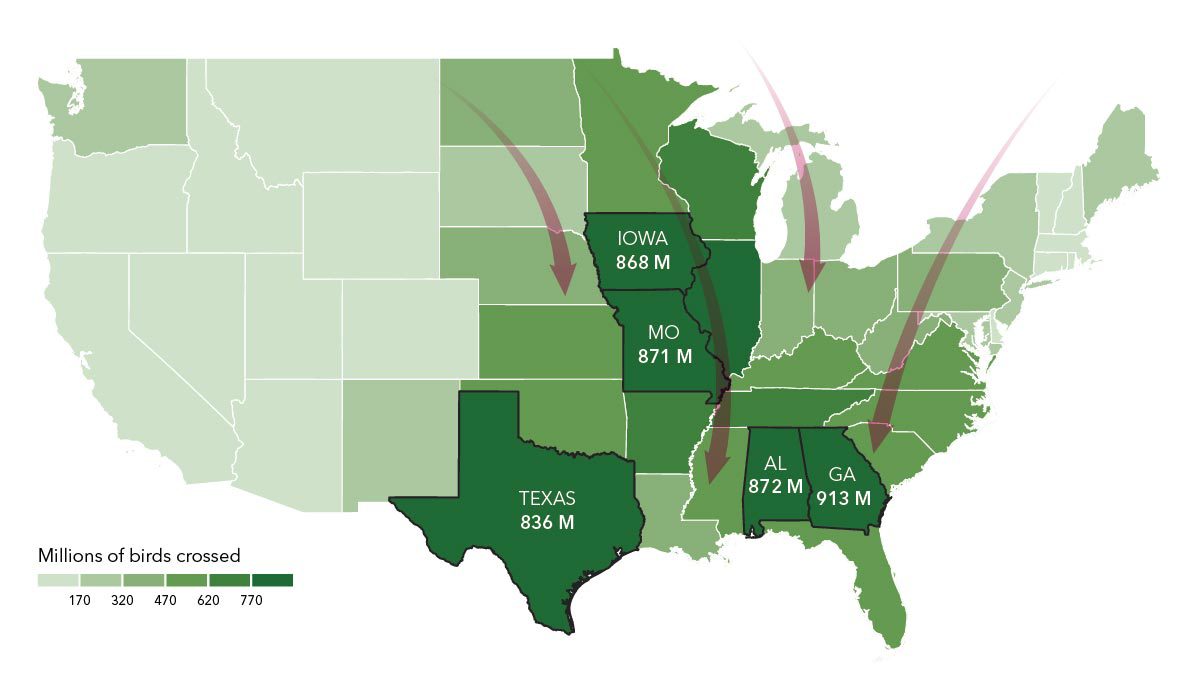

During last fall’s migration season, Georgia took the top prize for most birds— with 900 million birds migrating over the Peach State from August 1st to November 15th. But the birdiest night of fall migration peaked in neighboring Alabama, where 33 million birds flew over Baldwin County the evening of October 16—the highest nightly total for any county.

These bragging-rights stats come from the new online Migration Dashboard produced by BirdCast, a collaboration among scientists at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Colorado State University, and University of Massachusetts Amherst that uses weather radar and machine learning to track and forecast bird migration. BirdCast has been monitoring nightly bird migration via radar across the U.S.A. since 2018, but last spring the program launched the Dashboard tool to provide real-time migration data at the county level.

“In recent years, we’ve been able to visualize and forecast the movements of migrating birds on a continent-wide scale,” said BirdCast senior researcher Andrew Farnsworth, a research associate at the Cornell Lab. “That’s been fascinating, but now you can also get a feel for what’s going on in your own neck of the woods.”

Migration Dashboard provides real-time analytics about nocturnal bird migration, such as flight speed, direction, and altitude. In fall 2021, BirdCast indicated that southern states like Alabama and Georgia had the highest volumes of migrating birds, which makes perfect sense to radar ornithologists like Farnsworth and Adriaan Dokter.

“There’s always a tendency for migration to concentrate east of the Gulf [of Mexico],” said Dokter, a research associate at the Cornell Lab and member of the BirdCast team. The reasons, he said, lie in the basic needs of migrating birds: habitat, food, and favorable winds.

In autumn as birds move south from their breeding grounds, they seek out large swaths of forest to shelter and refuel during their grueling journeys. Dokter noted that the Appalachian Mountains—which are essentially 1,500 miles of unbroken trees running from Canada to the Deep South—is particularly enticing for migrants. The mountains collect birds from across the East, funneling them to the range’s southernmost points in Georgia and Alabama.

Large numbers of birds also migrate through Midwestern states like Iowa and Missouri. When flying on favorable tailwinds (that is, winds blowing out of the north), migrating birds tend to drift eastward due to prevailing west-to-east winds across the continent. Again, the birds are pushed toward Georgia and Alabama.

Watch Your Nightly Bird Migration in Real Time

This confluence of bird-migration rivers—where birds flying down the Appalachians meet birds drifting over from the Midwest—makes the Southeast a hub for nocturnal bird air traffic.

The highest-volume bird-migration nights are dictated by weather.

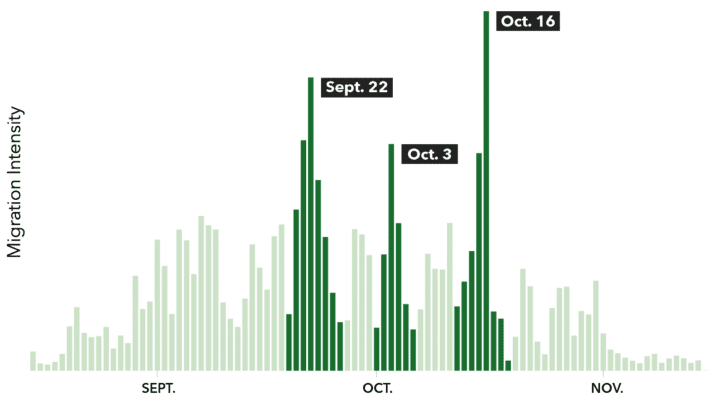

“Birds love to migrate with good tailwinds,” said Dokter. Indeed, the three biggest bird migration nights in fall 2021—on Sept. 22, Oct. 3, and Oct. 16—were all the result of high pressure systems that brought cold weather and favorable tailwinds out of the north. But Dokter theorizes there’s a difference in the makeup of species on those three big migration nights.

“It’s very likely the first peak is more long-distance migrants,” he said. “Later we see birds that stay in the U.S. to winter.” In other words, birds like warblers that migrate all the way to Central and South America depart first, whereas sparrows and kinglets that have less ground to cover migrate later.

As for fall 2022, Dokter says the new BirdCast tool adds a new element to birding the fall migration. “I’m going to sit there with Migration Dashboard, look around, and let the birds surprise me,” he says.

Benjamin Hack’s work on this story as a student editorial assistant was made possible by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Science Communications Fund, with support from Jay Branegan (Cornell ’72) and Stefania Pittaluga.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library