Golden-winged and Blue-winged Warblers Are 99.97 Percent Alike Genetically

By Gustave Axelson

From the Summer 2016 issue of Living Bird magazine.

July 6, 2016

On September 15, 1835, none other than John James Audubon wrote a letter to his friend the Rev. John Bachman, a Lutheran minister and eager naturalist in Charleston, South Carolina, in which Audubon mused that Golden-winged Warblers and Blue-winged Warblers might be the same species.

More than 180 years later, the most advanced ornithological methods of genome mapping and DNA sequence analysis show that Audubon was on to something. New research from a team led by scientists from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program show that, genetically speaking, Golden-winged and Blue-winged warblers are 99.97 percent alike. The findings—published in the September 2016 issue of Current Biology—could affect the conservation strategy for Golden-winged Warblers, a candidate for federal Endangered Species listing and one of the fastest-declining songbirds in North America (down 66 percent since the advent of the North American Breeding Bird Survey).

In many ways, Golden-winged Warblers and Blue-winged Warblers appear to be completely distinct species—they look different, they sing different songs, and in recent history they have lived in different places, with golden-wings in the Northeast and upper Midwest and blue-wings in a band slightly farther south from the Ozarks to the Appalachian Mountains. Where the two species overlap, they produce hybrids—including the forms called Brewster’s and Lawrence’s warblers.

In the study, Cornell Lab postdoctoral researchers Scott Taylor and David Toews—collaborating with partners from Cornell University’s Department of Biological Statistics and Computational Biology, the University of California at Riverside, and Environment and Climate Change Canada—showed that though Golden-winged Warblers and Blue-winged Warblers look distinct, those differences may be only skin deep—or in this case, feather deep.

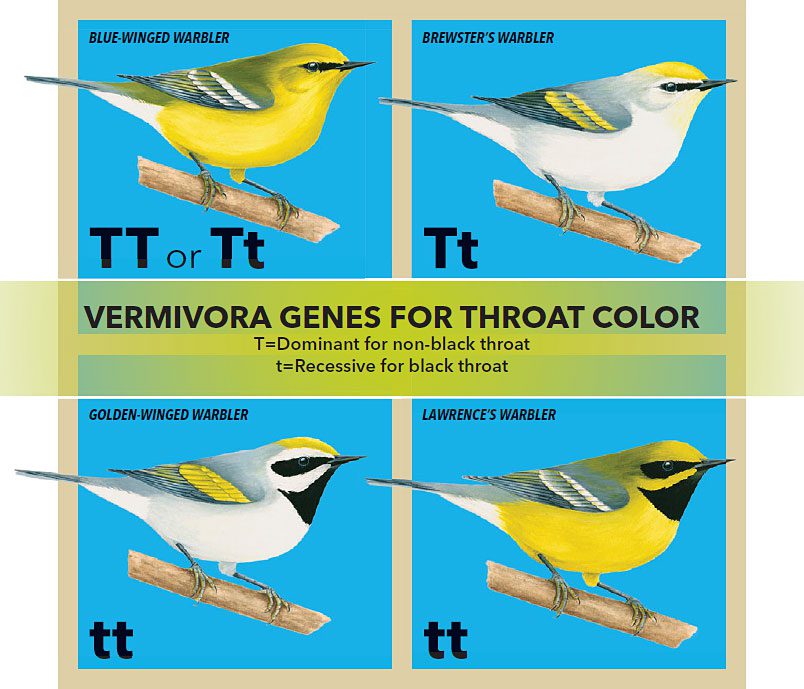

Taylor and Toews analyzed the entire genomes of both species, and they found only six regions (or .03 percent of the genome) that showed strong differences. One of these regions has a gene that appears to control throat coloration; the black throat of the Golden-winged Warbler is a classic Mendelian recessive trait, occurring only in birds that have a pair of recessive alleles for this trait. Another region likely controls body color; the yellow body of Blue-winged Warblers is another recessive trait. The research supports a model proposed by John T. Nichols of the American Museum of Natural History back in 1908 that the Brewster’s form of Golden- and Blue-winged warbler hybrids is an expression of dominant traits, and the Lawrence’s form is a recessive trait expression.

Put another way, the striking visual differences between Golden- and Blue-winged warblers could be considered akin to the differences between humans with and without freckles. The research also shows that golden-wings and blue-wings have even less genetic differentiation than two subspecies of the Swainson’s Thrush, the Olive-backed and Russet-backed forms.

“We think we have finally pinpointed the proverbial genomic ‘needle in the haystack’ between these taxa,” said Toews. “This is something that conservation practitioners have wanted for a very long time.”

The interactions between Golden-winged and Blue-winged warblers have been a dilemma for conservationists. Hybridization was perceived to be a threat to golden-wings, as it was thought that the more numerous Blue-winged Warblers would genetically swamp the rarer golden-wing gene pool. And it was thought that forest clearing by European settlers starting in the late 1700s caused the habitat changes that brought the two species together, thereby causing their hybridization.

In using the whole genome to look deeper into these birds’ evolutionary histories, Taylor and Toews made a surprising discovery—it turns out that these two species have probably been intermixing, at least intermittently, for thousands of years, well before Europeans colonized North America.

“This hybridization has been considered our [humans’] fault,” said Taylor. “But the propensity for these two species to hybridize is natural and appears to be part of their pre-European evolutionary history.”

Hybridization was one of the threats identified in the national Golden-winged Warbler Conservation Plan, published by a consortium of conservation groups and government agencies in 2012, but loss of young forest habitat was cited as the primary threat and most of the work driven by the plan has benefited both golden-wings and blue-wings. Hybridization, and the question of human causation, may play a role in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s upcoming decision on whether Golden-winged Warblers warrant federal protection under the Endangered Species Act. ESA protection for golden-wings has been argued in the courts, and a final decision by USFWS is due by 2017.

Tom Will, the USFWS Midwest Region Migratory Bird Coordinator, says the research shows that hybridization should not be considered a threat to the survival of Golden-winged Warblers.

“This research shows that [golden-wings and blue-wings] are super closely related, and in fact, the fundamental difference between them seems to be their plumage. So for humans to say, ‘Well, I want to protect golden-wings from blue-wings,’ that seems to be a largely aesthetic judgment, and not really justifiable from a wildlife or evolutionary standpoint,” Will said. “We need to think of these two species as an evolving complex.”

That complex, the Vermivora branch of the warbler tree, once held a third species—the Bachman’s Warbler, discovered by that same Lutheran minister and named by Audubon for his friend. Bachman’s Warbler is one of the few North American bird species to have gone extinct in modern times.

Will says that, in his personal opinion, golden-wings and blue-wings may have already evolved their own way to try to escape the Bachman’s Warbler’s fate.

“This system of golden-wings and blue-wings sharing genes may be a much better way of adapting to environmental change than we as humans could possibly figure out,” Will said. “I think that we should let it happen. It’s a good example of the beauty of evolution.”

“And apparently, it’s been going on for a long time.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library