Everybody Likes Bobwhite. Is That Enough to Save Them?

Hunters, birders, everybody seems to like Northern Bobwhite. And that's a good thing, because a team effort will be needed to restore quail populations across the South, Midwest, and East.

June 27, 2022

From the Summer 2022 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

In early March, 1,350 members of the Park Cities Quail Coalition flooded Armstrong Field House on the Dallas campus of Southern Methodist University for an annual fundraising event billed as “Conservation’s Greatest Night.” In recent years, the group of avid quail hunters has given its T. Boone Pickens Lifetime Sportsman Award—named for the late oil patch tycoon who was the organization’s chairman emeritus—to celebrities including Ted Turner, Tom Brokaw, and country music singer George Strait.

The oil and real estate high-rollers in attendance bid up prices on donated prizes, such as a quail hunt on Texas’s famed King Ranch, including travel on Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones’s team plane. When the dinner dishes were cleared and the bidding concluded, Park Cities had raised more than $1.5 million. Says Park Cities president Raymond Morrow, “There really isn’t any other wildlife organization that raises that much money in a single night.”

Since 2006, the group has raised $15 million to improve the prospects of the feathered rocket known as the Northern Bobwhite. Hunters from big-city billionaires to Midwest family farmers have long prized the rush of a covey of a dozen bobwhite taking wing at once.

But it’s not just hunters who love this plump bird. Though there are several quail species in the United States, there is only one east of the Great Plains—where the words “bobwhite” and “quail” are synonymous for the beloved bird with a black-and-white striped face and an eponymous song (poor… bob-WHITE). A lot of farmers create bobwhite habitat on their property just to see and hear the bird they remember from their childhoods.

“That’s a sign of spring, when you hear the bobwhite calling,” says Jackie Augustine, executive director of Audubon of Kansas. “They’re very kind of comical when you actually get to watch them, because their little heads stick out when they run.”

“Everybody loves to hear a quail, see a quail,” says Lee Metcalf, a biologist for the Missouri Department of Conservation who works with landowners on habitat conservation projects. “It doesn’t even matter if you’re a hunter. In this county, everybody likes quail.”

But as hunters and birders both know, the bobwhite has fallen on hard times. Since 1970, Northern Bobwhite numbers have dropped 77%, says Ken Rosenberg, retired scientist with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and lead author of the 2019 study that showed North America has lost 3 billion birds. According to Rosenberg, Breeding Bird Survey counts across the East, Southeast, and South show the same depressing trend for the little quail: “All the surveys were showing a very steep decline.”

But there’s hope. Where habitat persists—think of the mixed range and farmland of central Kansas, or hunting plantations of the Deep South—bobwhite continue to thrive. And where habitat is restored, bobwhite return.

The big question: Can Northern Bobwhite ever regain the abundance it enjoyed decades ago?

Not Strictly a Grassland Bird

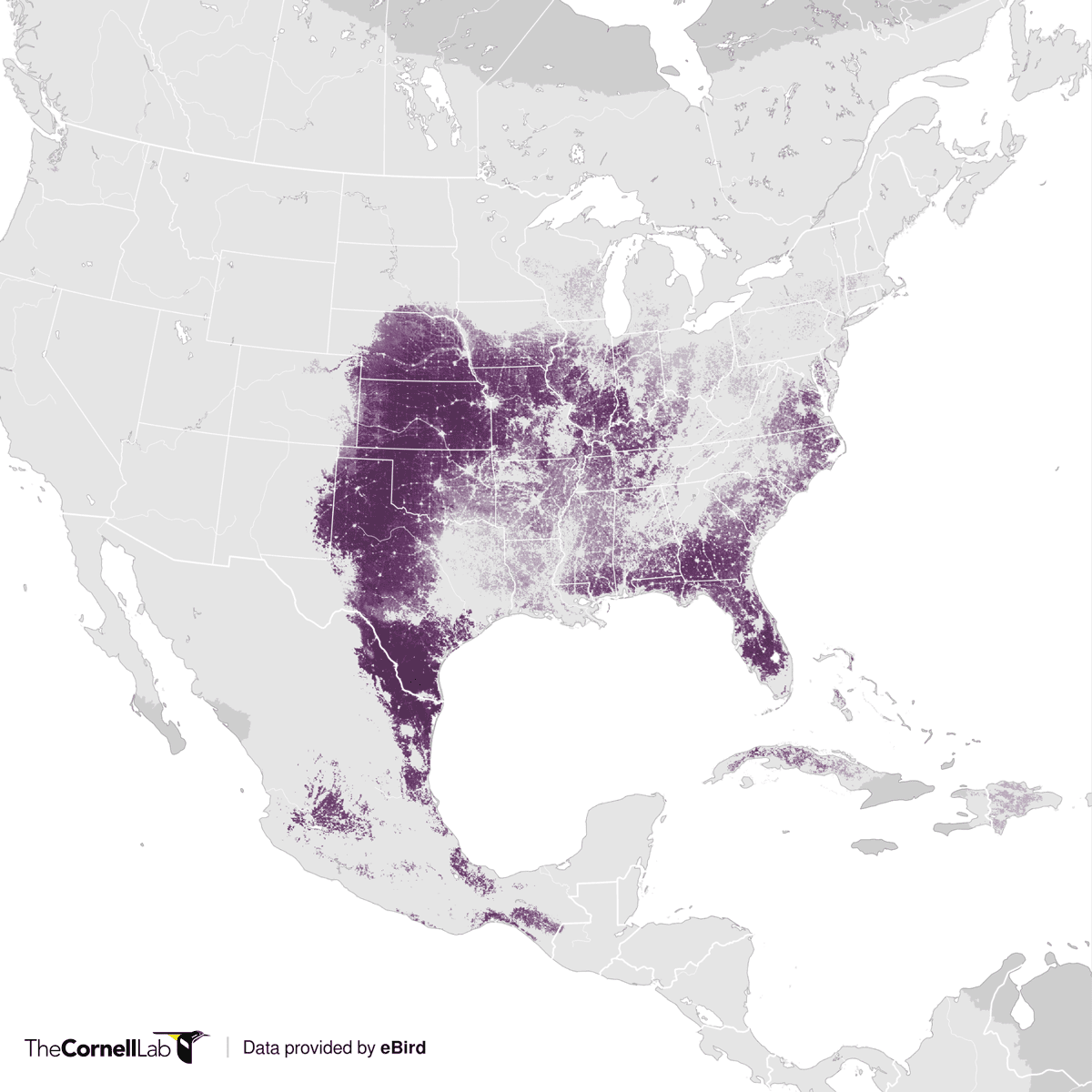

The Northern Bobwhite, Colinus virginianus, once lived from the rangeland of Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas all the way to the Atlantic Coast. They still do—recent eBird checklists tallied bobwhites in Maryland, New York’s Long Island, and Cape Cod in Massachusetts. But with few exceptions, quail numbers are far lower than they were just a few decades ago.

Most experts pin the long-term decline of Northern Bobwhite on loss of habitat. Put simply, bobwhite are in the same pickle as meadowlarks, Dickcissels, and prairie-chickens. Grassland bird species are experiencing “the steepest declines of any group of birds,” says Rosenberg.

But bobwhites are not strictly grassland birds, which makes their predicament unique and complicated. They need a mix of grass, forbs, and bare ground where thumb-sized chicks can forage freely; as well as woody cover such as brush, thickets, and wood edges. Woody cover is important for protection from raptors and cold weather. But too much cover, or none at all, generally means no bobwhite.

There was an abundance of such patchwork cover throughout the bobwhite’s range a century ago. Forests had been logged and were only beginning to grow back. Farms were small and diverse—fields of hay and grains were separated by raggedy brushy fencerows. Farmers often burned their fields.

In 1950, the typical Missouri farm was 40 acres with a multitude of crops and livestock—everything to support a family, says Lee Metcalf, the Missouri Department of Conservation biologist.

“All that stuff—small little fields, all in different stages and lots of areas undisturbed. There were no chemicals to set stuff back. There was no tractor and mower to go mow off stuff so it looked pretty,” Metcalf says. Posts were cut from hedgerows and firewood from woodlots. “They continually kept cutting on it so it had shrubby cover in it all the time. It was really good rabbit and quail hunting.”

The same was true throughout much of the Midwest, East, and South, says Rosenberg.

“The whole region was habitat, really,” he says. “Agricultural areas were just full of weedy margins, roadsides, and hedgerows. Those were great for birds. I call it accidental conservation.”

According to many experts, those conditions in the early and mid-20th century allowed bobwhite to thrive at levels perhaps never matched in history.

Since then, farms have grown larger, tidier, and less varied. A single cornfield today may cover what had been an entire family farm, without any of the diversity that proved so valuable to bobwhite and other wildlife.

“Clean agriculture,” says Rosenberg, “has just squeezed everything out of the landscape.”

In some areas, bobwhite have an additional problem. Without fire or logging, clearings and abandoned farm fields that were once open have now grown back into dense forest.

“No sunlight, no grass, no fire—well then, millions of acres became no longer suitable for bobwhite quail,” says quail biologist Robert Perez, coordinator for the Oaks and Prairies Joint Venture in Oklahoma and Texas.

Private Lands Are the Key

The prescription for bobwhite recovery is straightforward: reintroduce patchy patterns of grass, forbs, open woodland, and shrub to the landscape.

That’s easy in concept, but tough in practice. As much as 85% of potential bobwhite habitat is private land. Restoration is expensive, and it’s hard for habitat to compete with the profits from corn or soybeans.

“It’s an enormous private lands challenge,” says John Morgan, director of the National Bobwhite & Grassland Initiative. The NBGI is a collective of 25 state wildlife agencies and conservation groups formed in 1995 to restore wild bobwhite populations across their range.

Missouri has made more restoration progress than most states. In the northwestern part of the state, Lee Metcalf works with landowners in the 2C Quail Restoration Landscape to set aside marginal farmland for quail and create suitable habitat through practices such as prescribed burning. In wooded areas, landowners cut trees to open the canopy, allowing sunlight to reach wildflowers and grasses. Along the edge of fields, he recommends farmers “edge-feather” by felling mature trees and leaving them lie to provide woody cover.

The work isn’t easy or cheap, and sometimes it takes land out of production. Metcalf often points farmers to conservation subsidies in the federal Farm Bill, such as the Conservation Reserve Program and Environmental Quality Incentives Program, to compensate for expenses and lost income.

Where habitat has been restored, bobwhite have responded. Compared with control areas nearby, the quail restoration landscape has two to six times as many quail, according to surveys by the state conservation department.

Since most of the land suitable as bobwhite habitat is private, landowner participation is crucial, says Metcalf.

“It doesn’t work if you don’t have landowners cooperating with you and getting it done on the ground,” he says.

One of those landowners is Richard Phillips, who left his family’s farm in Missouri for college and a career in education, but came back as his brother’s health declined. Says Phillips, “I had two choices—either to become more involved or to watch the property deteriorate.”

While his brother had put some land into conservation programs, Phillips decided to forsake crop production and convert the entire 300 acres into wildlife cover. He established native forbs and brush, opened up woodlands, planted blackberry and sumac thickets, and grew wildlife food plots of wheat, sunflowers, corn, soybeans, and sorghum—all under Metcalf’s direction.

“When we do the burning, it’s a family affair. We try to burn about a fourth of the property off each year,” says Phillips, who like Metcalf is a lifetime member of the hunting and conservation group Quail Forever. “I told my grandkids, the quail are just a barometer. It gives us a reading on how the property is being cared for.”

Unlike Phillips, most farmers don’t have the luxury of devoting all their working land to quail. But so-called precision agriculture can help identify unprofitable acres that are better put to wildlife—turning red acres green.

David McCutchan raises Angus cattle and row crops on the family farm in northeastern Missouri. As a kid, “you comcould go out after school and kill your limit of quail without any problem,” he says. That changed by the mid-1990s.

McCutchan wanted to see bobwhite again, so he decided to convert some cropland to quail habitat, and the digital yield maps from his GPS-guided farm machinery showed him exactly where to find it—on acres that chronically underproduced because of shade, soil type, flooding, or lack of water.

He enrolled 20 acres of his field borders in a federal program that provides annual payments plus cost sharing for seeding. He edge-feathered some of his field borders and draws, and planted seven acres in a wildflower mix for pollinators such as bees and butterflies.

A combination of federal Farm Bill conservation incentives, Quail Forever donations, and state matching funds pays for the work. And it worked.

“When we harvested this fall we saw the most coveys that we’ve seen in years,” McCutchan says.

Where Bobwhite Still Fly High

In the pine savannas of northern Florida, the bobwhite has continued to thrive because of keen interest in the bird and aggressive use of prescribed fire.

“We call quail the fire bird,” says Alex Jackson, game bird research and extension biologist at the Tall Timbers Research Station north of Tallahassee. Fire is a common—many would say indispensable—element of bobwhite management in the pine woodlands of the Southeast, vital to keeping the understory from growing too thick and the open savannas from maturing into closed-canopy forest.

Tall Timbers sits in a region straddling the Florida-Georgia line where quail created an industry, a way of life, and an ecosystem—where they flourished even as they vanished elsewhere. Because of intense management of bobwhites as a game species, “I would say that down here they are at historical highs,” says Jackson.

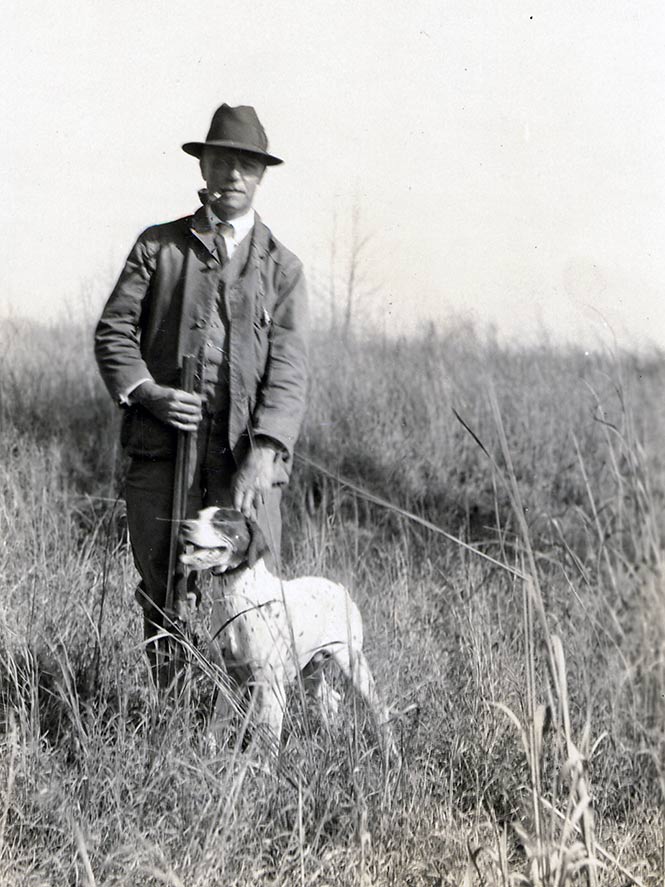

The quail era began in the late 1800s, with the demise of antebellum cotton plantations. Around the same time, shotguns became sufficiently lightweight and reliable so that upland hunting became popular. In bobwhite, sportsmen discovered a quarry that would sit for a pointing dog. And northern industrialists had money to spend on a fashionable sport.

In the late 1800s, rich hunters gobbled up entire plantations on either side of the state line, stately antebellum homes intact, and amassed hunting grounds by the thousands of acres devoted to the pursuit of “Gentleman Bob.” Teams of pointers or English setters ranged ahead in search of coveys as hunters followed in mule-drawn wagons. Among the best known of these bobwhite barons was financier and philanthropist Jeptha Homer Wade II from Cleveland, who in 1906 assembled 10,000 acres for his winter retreat called Millpond at the end of the rail line in Thomasville, Georgia.

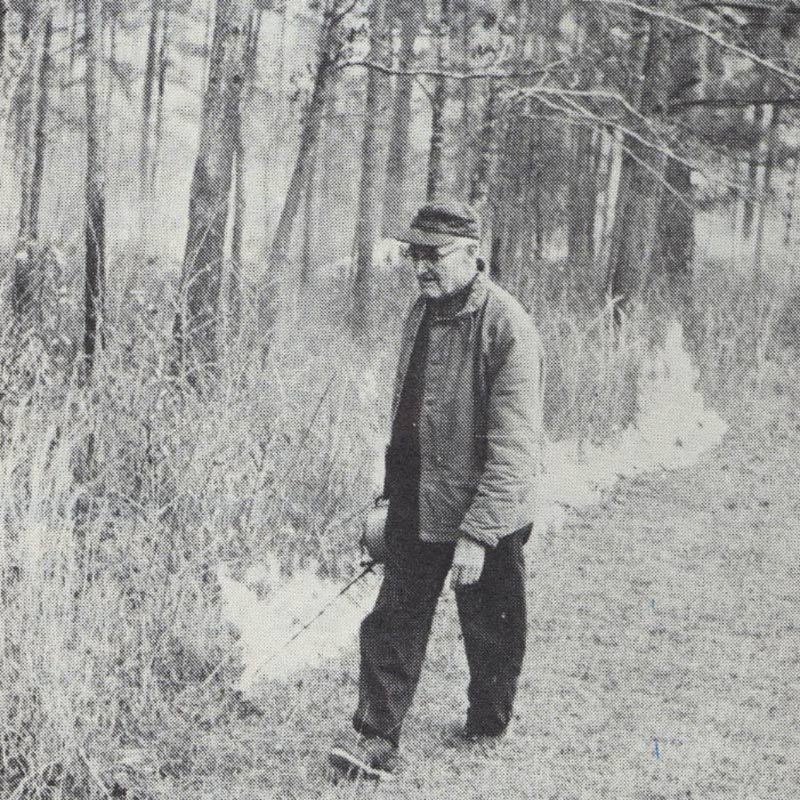

Beginning in the 1920s, ecologist and ornithologist Herbert Stoddard, a friend and colleague of Aldo Leopold, came to the area to study bobwhite and their habitat. Stoddard realized that bobwhite numbers declined as these new landowners “protected” habitat by preventing fires. So he began working with landowners to maximize quail numbers through selective logging and prescribed fire, a formula that worked magic on bobwhite. In 1958, Stoddard worked with the Beadel family from New York to convert their family’s hunting plantation into the Tall Timbers Research Station, a nonprofit organization dedicated to studying the role of fire in wildlife management.

Today much of Tall Timbers’s work is consulting and managing other private lands in the area. The Tall Timbers approach involves burning spots here and there “until you get a patchwork of different-aged vegetation structure that birds need to fulfill their requirements throughout their life,” says Jackson.

The early-successional habitat that benefits quail also helps other birds, such as Bachman’s Sparrows, Henslow’s Sparrows, and Red-cockaded Woodpeckers.

“We have absolutely the best longleaf pine systems on these private properties,” says Jim Cox, vertebrate ecology program director at Tall Timbers. “You can’t find anything that matches it on the public lands.”

To make sure the habitat endures, Tall Timbers acquires conservation easements on the private lands where it conducts habitat management. A conservation easement protects a plot of land from conversion to agriculture or any kind of development, by purchasing the development rights from the landowner.

“It’s one of the most effective tools we can possibly use,” says Cox. “It provides families with a tax benefit, but it also maintains the land use the property is currently in. We have about 150,000 acres now in easements in the region that will be permanently well-managed pine forest quail-hunting areas into perpetuity.”

Tall Timbers has also become the go-to authority in translocating wild bobwhite to other areas where habitat is suitable, but quail themselves have vanished. In Pennsylvania, where wild bobwhites disappeared 20 to 30 years ago, the Tall Timbers station is working with the U.S. Army and Pennsylvania Game Commission to restore habitat and reintroduce quail to the Letterkenny Army Depot in the Cumberland Valley. Andrew Ward, quail biologist for the Pennsylvania Game Commission, plans to move birds beginning in spring 2023 and keep introducing quail until the population numbers about 1,000.

Again, the restored bobwhite habitat is proving beneficial to several other bird species. Ward says that he’s already seen more Dickcissels, Eastern Meadowlarks, Indigo Buntings, and Yellow-breasted Chats—as well as a five-fold increase in American Woodcock—because of the increased stubble of woody cover created for quail.

Research Pays Off

Of the millions of dollars raised by the Park Cities Quail Coalition in Texas, most of their money goes into research.

“We want to have a magnifying effect with our dollars,” says coalition president Raymond Morrow.

Much of Park Cities’ largesse goes to the Rolling Plains Quail Research Ranch northwest of Abilene, which “studies everything that points toward quail,” says executive director Brad Kubecka.

Staff have banded or radio-tagged thousands of bobwhite and compiled the most comprehensive quail data set in the Lone Star State. The birds are tracked for survival and production, key information that can be tied into ranch management, says Kubecka.

The ranch also reintroduces quail through translocation, but only for landowners who have optimized large acreages of quail cover. Says Kubecka, “It’s kind of an incentive to get your habitat in shape.”

Gary Price, who raises cattle on a ranch south of Dallas, had his habitat in shape. “We really wanted to bring back quail … because we did have good habitat,” Price says.

Working with federal programs and at his own expense, he established native grasses on his 2,250 acres in Texas’s Blackland Prairie. The draws are filled with thickets of Texas ash and mesquite, and scattered trees provide shade for his cattle. Price installed fencing to rotationally graze cattle through a series of small paddocks. As a result, he has a profitable ranch with a reputation for sustainability. In 2018, Price was recognized with McDonald’s Flagship Farmer Award.

Price had all the components of bobwhite habitat. But few bobwhite. So he worked with Texas Parks and Wildlife Department on a bobwhite translocation project, using birds secured from Rolling Plains Quail Research Ranch and livetrapped near the Mexican border. Bobwhite were released on two consecutive springs—about 150 birds in all. Price also joined with several nearby landowners in the Western Navarro Bobwhite Restoration Initiative to build up the acreage of good quail habitat in Navarro County.

“We’ve got about 35,000 acres now of somewhat contiguous habitat,” he says. “The project has been very successful. These birds have stayed. They’re reproducing.”

Boots on the Grass

To see success on a single farm is one thing. To meaningfully restore bobwhite habitat on farmlands across the bird’s range is quite another.

More About Bobwhite Conservation

“To get it done you’ve got to have boots on the grass,” says Robert Perez, the coordinator for the Oaks and Prairies Joint Venture in Texas and Oklahoma. The Oaks and Prairies JV is a partnership of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, American Bird Conservancy, and other groups that work with private landowners to improve habitat for struggling species such as bobwhite.

“Boots on the ground—that’s expensive. Personnel is expensive,” says Perez. “We need an army of biologists to be out there, door knocking and developing those relationships.”

Even the millions in conservation funding available for the beloved bobwhite is too little to restore much more than a fraction of the hundreds of millions of acres that once supported abundant populations of quail. Investments in bobwhite habitat haven’t kept up with the need. For example, the acreage enrolled in the flagship program of the Farm Bill’s Conservation Title—the Conservation Reserve Program—has declined from 36.7 million acres in 2007 to around 22 million acres today.

CRP is “just not at a scale that will work long term,” says Rosenberg, the retired Cornell Lab scientist. “Without some permanently set aside and protected habitat, like there is for wetlands and waterfowl and wildlife refuges, without that kind of habitat system for grassland birds, I think the prognosis is pretty dismal.”

With that in mind, several conservation groups—including Quail Forever, the National Wildlife Federation, and American Bird Conservancy—are imploring Congress to pass a North American Grasslands Conservation Act that would prioritize grassland protection and provide funding incentives to restore grasslands on farms and ranches. Proponents say it would benefit open-country wildlife the way the North American Wetlands Conservation Act protected waterfowl habitat and helped restore continental populations of ducks.

The politics and projects that promote grassland restoration are often led by hunting organizations willing to give money and effort to restore populations of upland game birds, whether pheasants, prairie grouse, or bobwhite. And that creates the potential for powerful partnerships with birding organizations, says Jackie Augustine, executive director of Audubon of Kansas.

“There’s lots of opportunities to be synergistic,” Augustine says. “Who is on the front lines of conservation? It’s the hunters that are seeing declines, and the birders that are seeing declines. I think both types of organizations are seeing where the conservation needs are. And there are opportunities to work together.”

The bobwhite fan club needs to get bigger than just hunters and birders, says John Morgan, director of the National Bobwhite & Grassland Initiative. According to Morgan, passing a big piece of legislation like a North American Grasslands Act will require promoting grasslands restoration benefits beyond quail—such as soil health, water quality, and carbon sequestration.

“If we can start coupling the wildlife message with all those other environmental benefits plus the direct human benefit,” says Morgan, “now we’re talking to enough people where we can make bobwhite an icon for environmental health.”

Freelance writer Greg Breining is a frequent contributor to Living Bird. He writes about wildlife, the environment, health, and science.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library