American Redstarts Can Speed Up Their Migration, but There’s a Cost

Research has uncovered a possible link between when American Redstarts leave for spring migration, how fast they travel, and how likely they are to survive.

April 1, 2024

From the Spring 2024 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

For a small migratory songbird like an American Redstart, driven by an evolutionary imperative to pass on its genes to the next generation, every day—and every spring—counts. A delay during spring migration can cause a bird to arrive late to its breeding grounds and miss its best chance at claiming a territory and finding a mate.

And missing a single breeding season can mean a huge drop in the number of descendants a redstart may leave behind.

“On average, migratory songbirds only live a year or two, so keeping to a tight schedule is vital. They’re only going to get one or two chances to breed,” says Bryant Dossman, a scientist at Georgetown University who specializes in the behavioral and population ecology of migratory birds.

Dossman was lead author on research published in the journal Ecology in February 2023 that showed redstarts are capable of migrating faster to make up for lost time, if they are late leaving for their journey north. But migrating faster may come with a steep cost—a higher rate of mortality.

Dossman worked on the research as a PhD student at Cornell University, using 10 years of data from a long-term study of American Redstarts in Jamaica to calculate when birds typically headed north in the spring. From there, he could determine whether an individual bird’s departure date (early, average, or late) affected the likelihood that it survived to return to Jamaica the following season. Annual survival, the study found, was about 6% lower for birds that left late.

“The behavioral shifts documented in this research remind us that the manner in which climate change affects animals can be subtle and, in some cases, able to be detected only after long-term study,” says Amanda Rodewald, a study coauthor and Dossman’s doctoral advisor at Cornell, where she is the senior director of the Center for Avian Population Studies at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

For a hint at why late birds were less likely to live to see another year, Dossman and his colleagues looked at tracking data for the redstarts as they traveled north. Using a combination of Motus radio-transmitter tags and light-level geolocators (devices that record a bird’s estimated locations based on sunrise and sunset times), the researchers gathered data on the pace of migration for 30 birds with a range of departure dates, from late April to mid-May. The redstarts that left relatively late—around 10 days later than average—migrated an impressive 43% faster than those that left on time. Whereas the punctual birds covered an average of 70 miles a day, the stragglers playing catchup averaged almost 100 miles a day.

American Redstart Pace of Spring Migration

Research published in the journal Ecology tracked the migration rates of individual American Redstarts on their spring journeys north from Jamaica. The redstarts that departed their wintering grounds later traveled faster than the earlier-departing birds—in some cases as much as five times faster.

| Departure Date from Jamaica | Arrival Date on Breeding Grounds | Breeding Grounds | Average Miles Per Day |

| April 25 | May 22 (27 days) | New York | 62 |

| April 27 | June 9 (43 days) | Iowa | 43 |

| May 2 | May 23 (21 days) | Iowa | 89 |

| May 9 | May 23 (14 days) | Michigan | 121 |

| May 15 | May 25 (10 days) | Illinois | 180 |

| May 17 | May 25 (8 days) | Michigan | 216 |

“Honestly, I was expecting some kind of an effect [of departure date], just based on experience working with these birds,” says Dossman. “What I wasn’t expecting was the magnitude of the effect.”

Dossman and his collaborators believe that this increase in speed explains why survival is lower for late migrators. Traveling faster, by doing things like decreasing the amount of time they spend resting and refueling, is riskier and more energetically demanding.

“What we’re finding is that these migratory passerines are behaviorally plastic—they can adjust their migration rate to accommodate these delays, just like you and I would do if we were late for work,” says Dossman. “But for these birds, it comes at a cost, which is that they’re less likely to survive because of the things they’re doing to speed up.”

The long-term dataset used for this study shows that climate change may be making it harder for redstarts to stay on schedule, because Jamaica, their nonbreeding season home, is getting drier. The drier weather may mean fewer insects—which means less food for warblers, which means it may take them longer to put on enough weight to fuel their northward migration. A recent follow-up study also by Dossman, who is currently a postdoctoral fellow at Georgetown University, found that in especially dry years, the Jamaica-wintering redstarts that migrate the farthest to northern breeding grounds in places like Ontario have lower overall survival than birds with shorter, less grueling treks to breeding sites in places like Illinois.

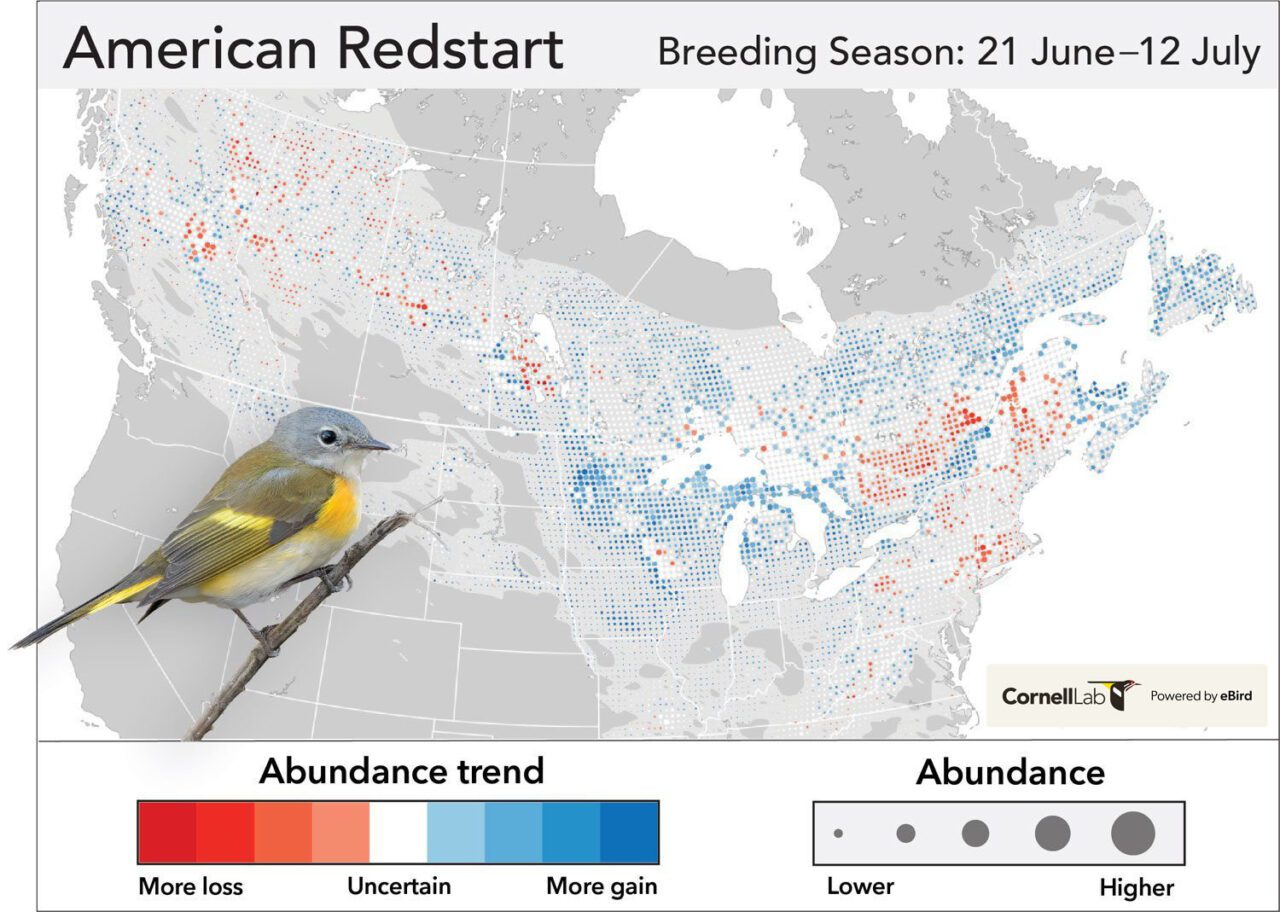

Although redstart populations are stable or even increasing in many areas, eBird Trends data suggests that they’re declining in some northern and eastern portions of their range. Such is the uneven nature of climate disruption, says Peter Marra, another coauthor on the redstart-migration research.

“Understanding how animals can compensate is an important part of understanding where the impacts of climate change will play out. In this case, we may not lose a species entirely, but it is possible that populations of some species may go extinct locally due to climate change,” says Marra, the dean of Georgetown’s Earth Commons Institute for the Environment and Sustainability.

What’s more, redstarts are probably not the only birds feeling these impacts. While this research was made possible by a long-term study of redstarts in Jamaica that’s been led by Marra since 1987, “redstarts aren’t unique,” Dossman says. “They’re representative of an entire group of songbirds. I think these effects are widespread.”

Kristen Covino, an ornithologist at Loyola Marymount University and expert on warbler migration timing who wasn’t involved in Dossman’s project, noted the small sample size for the data on migration speed. But she thinks the results are “powerful” and open up a lot of new questions.

“Let’s say there’s an individual that’s late one year, and therefore, we see faster migration,” she says. If the next year that same bird departs on time or early, she wonders, “do we see that it migrates more slowly than it did the year that it departed late?”

Collecting data that detailed on individual birds over multiple years is challenging. But, says Marra, this study is an example of how the science of bird-migration research is breaking new ground.

“As we automate and use new technologies to study birds,” says Marra, “I think more and more insights like this into the black box of migration are going to be revealed.”

About the Author

Freelance science writer Rebecca Heisman is a frequent contributor to Living Bird. Based in Walla Walla, Washington, she is the author of the book Flight Paths: How a Passionate and Quirky Group of Pioneering Scientists Solved the Mystery of Bird Migration.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library