Get the Lead Out: The Poisoning Threat From Tainted Hunting Carcasses

by Matthew L. Miller

October 15, 2009

Here’s my father-in-law’s idea of a bird feeder: he invites hunters to dump deer entrails in a cornfield beside his northeast Iowa dairy farm, where he can easily watch the birds they attract. Unconventional, perhaps, but it works. Within hours, Bald Eagles begin swooping down for the easy pickings. He enjoys sharing with his grandchildren and guests the spectacular sight of 10 or more of these magnificent eagles feeding on the leftovers. The hunters, for their part, think they’re doing a bit of good, too, by providing food for the birds in winter. Everyone involved admires the eagles and wouldn’t think of poisoning them.

Unfortunately, that is probably exactly what they’re doing. As numerous recent studies have concluded, many gut piles are full of tiny, highly toxic fragments of lead from rifle bullets, which are all too often ingested by the animals that eat the entrails.

“We are seeing some very acute cases of lead poisoning in Bald Eagles,” says Kay Neumann, wildlife rehabilitator and executive director of Saving Our Avian Resources (SOAR). “The eagles are experiencing respiratory distress, they’re puking green, they’re defecating green,” she says. “It makes my winter very unpleasant.”

Eighty-two of the 115 Bald Eagles brought to Iowa wildlife rehabilitators since 2004 have been tested for the presence of lead; of those, 62 contained abnormally high lead levels in their blood, liver, or bone.

“In the winter, it rains sick and dying eagles in Iowa,” says Neumann. “Avian research often points to something going on in the environment, whether it’s DDT or West Nile virus. And there’s something going on here with lead ammunition.”

Neumann’s research in Iowa points to the same conclusion as a growing number of studies around the world: fragments of lead from rifle bullets in big-game carcasses pose threats to scavenging birds—and quite likely to humans as well.

The most widely used rifle bullets for big-game hunting have a lead core encased in a copper jacket. These bullets mushroom on impact and can send a spray of tiny lead fragments through the animal, especially if the bullet hits a bone. Studies on deer carcasses have shown that lead-core bullets fragment much more than most researchers previously realized. Discarded deer entrails (“gut piles”) and rifle-killed carcasses that hunters are unable to find often contain hundreds of tiny, soft lead fragments.

“I never realized how much lead-core bullets fragment,” says Golden Eagle researcher Rob Domenech. “If the majority of avian researchers didn’t realize this, it’s no surprise that hunters and the general public don’t either.”

Researchers have now gathered substantial data, but the question remains: Will hunters and the general public recognize that lead ammunition is a major threat to wildlife? The future of the wild California Condors and possibly other scavenging birds most likely depends on how that question is answered.

People have understood the harmful effects of lead for more than 2,000 years. Greek poet Nicander of Colophon wrote of the negative health consequences of lead in 200 B.C., and the Romans recognized (too late to stop the decline of their empire, according to some historians) that lead plumbing caused a variety of ailments.

Lead is a powerful neurotoxin with significant health risks—even if only very low levels are absorbed—not only for birds, but also for people. Lead toxicosis can cause depression, lethargy, anorexia, and a long list of other maladies. Human fetuses that absorb lead show higher levels of autism and attention deficit disorder, and lower IQs. And a study on rhesus macaques suggests a correlation between very low levels of lead exposure and higher risks of Alzheimer’s disease.

Many states have official programs to examine the amount of lead in playground equipment, and lead found in Chinese-made toys has made national news. Still, lead remains a popular component in recreational fishing weights and in ammunition for shotguns, rifles, and handguns.

Federal legislation banned lead shot for all waterfowl hunting in 1991 due to the well-documented lead poisoning of ducks, loons, and other birds that ingest tiny lead shotgun pellets that settle in the mud on the bottom of lakes, ponds, and marshes frequented by waterfowl hunters. The most popular duck-hunting areas tend to be public marshes and private hunting clubs, where a heavy volume of shooting is the norm. Much spent shot is deposited in the water. In wetlands, with little water flow, this shot accumulates over the years—a toxic situation when lead was involved. Now duck hunters are required to use steel or other nonlead shot, which is not harmful to wildlife if it is ingested.

In contrast, lead-core rifle bullets have traditionally been considered at most a minor conservation issue. Unlike duck hunters, deer hunters don’t tend to congregate in the same areas. They also don’t shoot a high volume of ammunition, and their ammunition consists of single bullets, not thousands of small shot pellets. It seemed unlikely to most people, including researchers, that individual rifle bullets—which often pass completely through big-game animals—would pose much more than an isolated threat to wildlife or humans.

And then condors started dying.

The Peregrine Fund had begun releasing California Condors back to the wild in Arizona in 1996, nine years after the last wild condors were captured to use in a captive-breeding program.

“When we first released the birds, we didn’t know if they would successfully nest, or breed, or be able to find food,” says Rick Watson, vice president of The Peregrine Fund. “They did that all quite well, but we were still losing a lot of birds to early mortality.”

Blood tests revealed that most of these birds had died of lead poisoning. At first, researchers searched for a single source of the contamination, such as a shooting range where the condors might be scavenging. It was difficult for the researchers to imagine how else the birds could be ingesting so much lead.

Peregrine Fund researchers already had radio-tags attached to the condors, and they started recording their locations every two hours. Over the course of several years, the researchers gathered huge amounts of data detailing where the birds landed and what they ate. And what they ate, it turns out, were lots of gut piles and rifle-killed deer remains that hunters had not found.

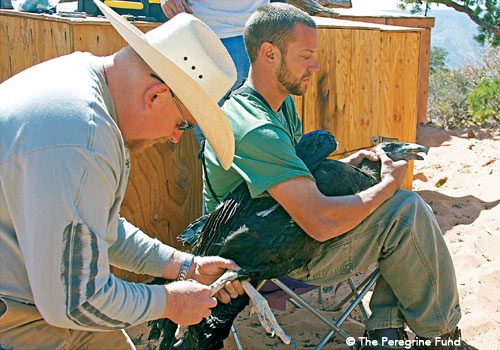

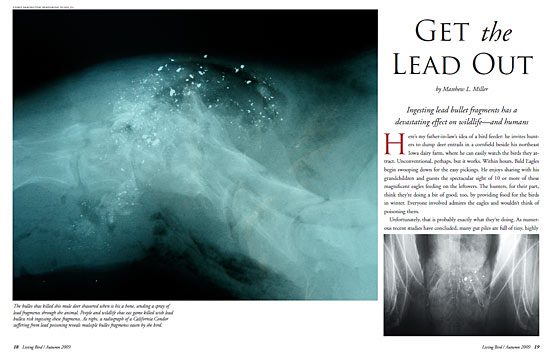

Biologists began trapping the birds every year, to test for lead in their blood and to detoxify those that had abnormally high lead levels. Detoxification requires chelation therapy, a costly, complicated, and invasive procedure that involves injecting the birds with organic compounds that bind to the lead and are then removed from the blood. X-rays revealed small lead bullet fragments in the stomachs of condors that had toxic lead levels in their blood.

“There was a tight correlation between the hunting season and high levels of lead in the birds’ blood,” says Watson. “As the hunting season begins, the birds congregate in the areas used most by hunters. At the current rates of lead exposure, California Condors can’t survive in the wild on their own while lead ammunition is being used in their foraging range.”

Peregrine Fund staff, who pride themselves on their nonconfrontational approach, weighed the options for reducing the California Condors’ exposure to lead. The issue, however, was about to become a lot more public—not due to the condors, but because of the potential effect of lead bullet fragments on human health.

William Cornatzer, a physician in Bismarck, North Dakota, watched a presentation on the California Condor at his first meeting as a Peregrine Fund board member. He felt shock when an x-ray of a deer carcass containing hundreds of pieces of lead shrapnel appeared on the screen.

Cornatzer, an avid big-game hunter, had previously believed that proper butchering would remove all traces of lead from a game animal, but after seeing the x-ray, he had doubts. He decided to test random samples of rifle-killed venison and determine if any lead was present. He and two other researchers chose the Hunters for the Hungry Food Bank, where hunters donate venison. The researchers enlisted the help of the North Dakota Department of Game and Fish, which randomly selected ground venison packets from different butchers and delivered them to the state health department for analysis.

Of 100 one-pound packets, 59 contained small metal fragments in the meat—fragments that further analysis revealed to be pure lead.

“These are very soft fragments that you don’t feel when you bite down on them. It’s like lead powder,” Cornatzer says. “And lead powder is much easier to absorb in the blood stream.”

North Dakota recalled all the meat from the Hunters for the Hungry program, as did neighboring Minnesota. “It was a tough decision,” says Stephen Pickard, medical epidemiologist for the North Dakota Department of Health. “But if we had found metal fragments in any other type of meat, we would have pulled it immediately. We did not believe we should treat hunter-killed venison differently.”

Cornatzer notes that any lead exposure in children is too much, and he has advocated that hunters immediately throw away lead-shot meat and begin using nonlead ammunition. Although hunters aren’t collapsing from lead poisoning, Cornatzer says the long-term impacts could be severe.

“I have patients who tell me they’ve been eating wild game killed with lead bullets for forty years with no problems,” he says. “Forty years ago, someone could have said the same thing about smoking cigarettes. Just because problems don’t manifest themselves immediately doesn’t mean they aren’t going to have long-term health consequences.”

A subsequent study of blood lead levels in 738 North Dakota residents, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and the North Dakota Department of Health, found that people who eat wild game harvested with lead appear to have higher blood lead levels than people who don’t. The study also showed that the more recent the consumption of wild game harvested with lead bullets, the higher the level of lead in the blood.

To examine the potential impacts of using lead bullets in hunting, The Peregrine Fund convened a symposium in Boise, Idaho, in May 2008, titled “Ingestion of Lead from Spent Ammunition: Implications for Wildlife and Humans.” According to Rick Watson, the presentations were “eye-opening.” Researchers from around the world reported detecting elevated blood lead levels in a variety of bird species, principally scavengers.

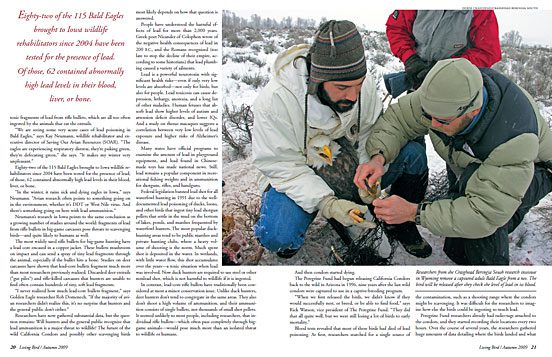

Derek Craighead and Bryan Bedrosian of the Craighead Beringia South research institute in Wyoming investigated blood lead levels in ravens, eagles, and other wildlife around Grand Teton National Park, an area with one of the highest densities of elk hunters in the country. Fifty percent of 307 ravens tested during the hunting season showed elevated blood lead levels. The researchers also found that the annual median blood lead level of ravens during the hunt is correlated with the number of animals harvested that season.

“The first spike in blood lead levels of birds tested was the first day of hunting season,” says Bedrosian, the institute’s avian program coordinator. “Of 231 birds tested before the hunting season, two had elevated blood lead levels. If birds were picking up lead from a background source, you would see elevated levels all year long.”

Lead stays in the blood for only two weeks, making it easy to verify how recently it was ingested. It’s important to note that lead ingestion is a cumulative problem. After being mobilized in the blood, lead is deposited in soft tissue for three months. From there, it moves into bone, marrow, and brain, where it remains for the rest of the bird’s (or other organism’s) life.

Bedrosian and Craighead also found elevated blood lead levels in Bald and Golden eagles, with 75 percent of the 63 eagles tested exhibiting elevated lead levels, and 14 percent exhibiting levels indicating clinical poisoning.

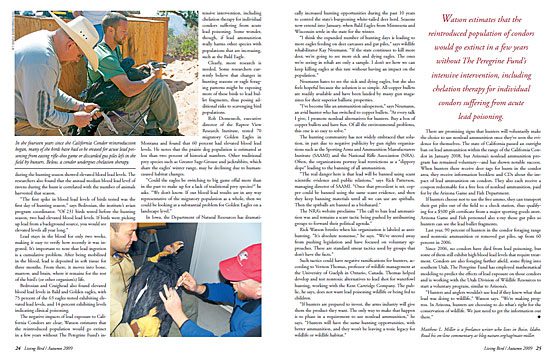

The negative impacts of lead exposure to California Condors are clear; Watson estimates that the reintroduced population would go extinct in a few years without The Peregrine Fund’s intensive intervention, including chelation therapy for individual condors suffering from acute lead poisoning. Some wonder, though, if lead ammunition really harms other species with populations that are increasing, such as the Bald Eagle.

Clearly, more research is needed. Some researchers currently believe that changes in hunting seasons or eagle foraging patterns might be exposing more of these birds to lead bullet fragments, thus posing additional risks to scavenging bird populations.

Rob Domenech, executive director of the Raptor View Research Institute, tested 70 migratory Golden Eagles in Montana and found that 60 percent had elevated blood lead levels. He notes that the prairie dog population is estimated at less than two percent of historical numbers. Other traditional prey species such as Greater Sage-Grouse and jackrabbits, which share the eagles’ winter range, may be declining due to human-caused habitat changes.

“Could the eagles be switching to big game offal more than in the past to make up for a lack of traditional prey species?” he asks. “We don’t know. If our blood lead results are in any way representative of the migratory population as a whole, then we could be looking at a substantial problem for Golden Eagles on a landscape level.”

In Iowa, the Department of Natural Resources has dramatically increased hunting opportunities during the past 10 years to control the state’s burgeoning white-tailed deer herd. Seasons now extend into January, when Bald Eagles from Minnesota and Wisconsin settle in the state for the winter.

“I think the expanded number of hunting days is leading to more eagles feeding on deer carcasses and gut piles,” says wildlife rehabilitator Kay Neumann. “If the state continues to kill more deer, we’re going to see more sick and dying eagles. The ones we’re seeing in rehab are only a sample. I don’t see how we can keep killing eagles at this rate without having an impact on the population.”

Neumann hates to see the sick and dying eagles, but she also feels hopeful because the solution is so simple. All-copper bullets are readily available and have been lauded by many gun magazines for their superior ballistic properties.

“I’ve become like an ammunition salesperson,” says Neumann, an avid hunter who has switched to copper bullets. “At every talk I give, I promote nonlead alternatives for hunters. Buy a box of copper bullets and have fun. Of all the environmental problems, this one is so easy to solve.”

The hunting community has not widely embraced that solution, in part due to negative publicity by gun rights organizations such as the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers Institute (SAAMI) and the National Rifle Association (NRA). Often, the organizations portray lead restrictions as a “slippery slope” leading to the banning of all ammunition.

“The real danger here is that lead will be banned using scant scientific evidence and public relations,” says Rick Patterson, managing director of SAAMI. “Once that precedent is set, copper could be banned using the same scant evidence, and then they keep banning materials until all we can use are spitballs. Then the spitballs are banned as a biohazard.”

The NRA’s website proclaims “The call to ban lead ammunition was and remains a scare tactic being pushed by antihunting groups to forward their political agenda.”

Researchers from the Craighead Beringia South research institute in Wyoming catch raptors such as this Bald Eagle to test the lead levels in their blood.

Condors are susceptible to lead poisoning from eating rifle shot found in carrion. Most big-game bullets have a lead core that can shatter into lead fragments upon impact, especially when they hit a bone.

Treating condors with a technique called chelation therapy is a difficult and painstaking procedure. In January 2008, California banned lead ammunition within the condor's range.

Lead fragments, like these in a recently killed mule deer, are difficult to see without the help of an X-ray image. People and wildlife are at risk for consuming lead when they eat game killed with lead bullets.

This is an X-ray of a California Condor that was suffering from lead poisoning symptoms. The X-ray clearly shows the bird had eaten lead bullet fragments.

In the 14 years since California Condor reintroduction began, many have had to be treated for acute lead poisoning.

Rick Watson bristles when his organization is labeled as antihunting. “It’s absolute nonsense,” he says. “We’ve steered away from pushing legislation and have focused on voluntary approaches. These are standard smear tactics used by groups that don’t have the facts.”

Such tactics could have negative ramifications for hunters, according to Vernon Thomas, professor of wildlife management at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada. Thomas helped develop and test nontoxic alternatives to lead shot for waterfowl hunting, working with the Kent Cartridge Company. The public, he says, does not want lead poisoning wildlife or being fed to children.

“If hunters are prepared to invest, the arms industry will give them the product they want. The only way to make that happen is to phase in a requirement to use nonlead ammunition,” he says. “Hunters will have the same hunting opportunities, with better ammunition, and they won’t be leaving a toxic legacy for wildlife or wildlife habitat.”

There are promising signs that hunters will voluntarily make the choice to use nonlead ammunition once they’ve seen the evidence for themselves. The state of California passed an outright ban on lead ammunition within the range of the California Condor in January 2008, but Arizona’s nonlead ammunition program has remained voluntary—and has shown notable success. When hunters there receive deer tags for hunts in the condor area, they receive information booklets and CDs about the impact of lead ammunition on condors. They also each receive a coupon redeemable for a free box of nonlead ammunition, paid for by the Arizona Game and Fish Department.

If hunters choose not to use the free ammo, they can transport their gut piles out of the field to a check station, thus qualifying for a $500 gift certificate from a major sporting goods store. Arizona Game and Fish personnel also x-ray those gut piles so hunters can see the lead bullet fragments.

Last year, 90 percent of hunters in the condor foraging range used nontoxic ammunition or removed gut piles, up from 60 percent in 2006.

Since 2006, no condors have died from lead poisoning, but some of them still exhibit high blood lead levels that require treatment. Condors are also foraging farther afield, some flying into southern Utah. The Peregrine Fund has employed mathematical modeling to predict the effects of lead exposure on those condors and is working with the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources to start a voluntary program, similar to Arizona’s.

“Hunters and anglers wouldn’t use lead if they knew what that lead was doing to wildlife,” Watson says. “We’re making progress. In Arizona, hunters are choosing to do what’s right for the conservation of wildlife. We just need to get the information out there.”

Matthew L. Miller is a freelance writer who lives in Boise, Idaho. Read his on-line commentary at blog.nature.org/tag/matt-miller.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library