For Tropical Wren, Songs and Species Evolve in Isolation

By Pat Leonard

January 26, 2016

Long-isolated bird populations of the same species may gradually evolve differences in their DNA, appearance, and songs. But at what point during this divergence can scientists confidently stamp a particular population as having changed enough to be considered a separate species?

A group of Cornell undergraduates working in Costa Rica tried to answer this question with an elegant “what if?” experiment which has now been published in a top scientific journal. What if isolated populations of White-breasted Wood-Wrens did come into contact again–would they still be able to interbreed? The students’ research essentially posed this question to the birds themselves.

“If we think that two of the isolated populations would interbreed if brought together then we should call them the same species,” says Ben Freeman, an instructor who guided the students’ work as part of Cornell’s Advanced Tropical Field Ornithology course. “If we think they would not interbreed, maybe we should be considering them different species.”

The White-breasted Wood-Wren is a small tropical wren with rufous wings and bold black-and-white bars on its face. It lives in lowlands from southern Mexico through northern South America. Some populations have been isolated by physical barriers, such as the Andes Mountains and the mighty Amazon River, for at least 5 million years. Their songs have changed noticeably. The students wondered whether wrens in Costa Rica, where their field class was located, could still recognize White-breasted Wood-Wrens from other parts of their range.

In order to breed, the wrens have to recognize each other as the same species, primarily through song. Male and female White-breasted Wood-Wrens, which look alike, would respond to a male’s song in different ways. The female would perceive a potential mate; the male would consider the singer a threat and try to chase him away by countersinging or moving toward his rival.

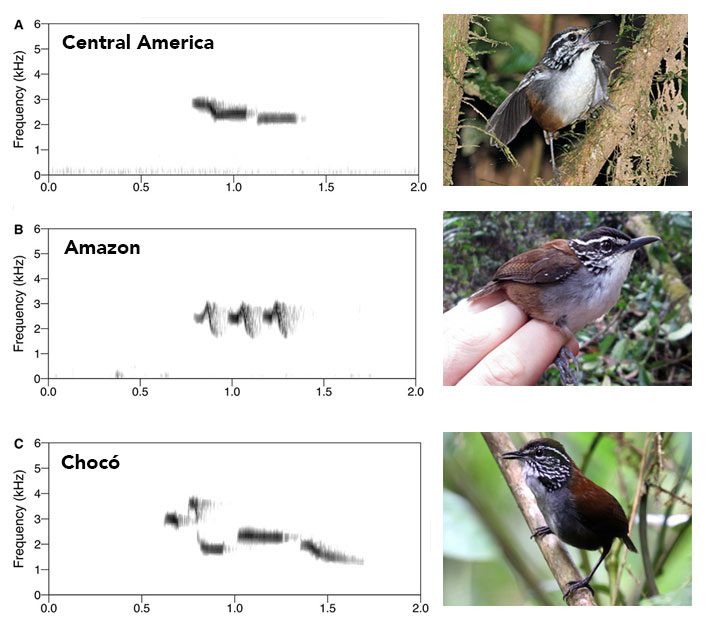

The experiment focused on three distinct White-breasted Wood-Wren populations: one in Central America, one in the Amazon region, and the third in the Chocó region of Colombia and Ecuador. The three populations sing different-sounding songs.

Since it would be highly impractical, not to mention unethical, to transport live birds from one region to another and then wait around (perhaps for years) to see if they breed, the students used song recordings of wrens from each of the three populations. They played them back and watched the reaction of the White-breasted Wood-Wrens living near the La Selva Biological Station in Costa Rica, part of the Central American wren population.

“First we used speakers to play a song from the local population. The wrens—we presume the males—recognized the song and behaved aggressively,” says Freeman. “When we played back the song of the wrens from the Chocó region, the Costa Rica wrens also reacted aggressively, so those two populations do still ‘understand’ one another and could conceivably still interbreed.”

But when the Costa Rica wrens heard the songs of the Amazon wrens, they did not react, apparently no longer able to recognize the song. The inference is that if these two populations cannot communicate they could not breed—and should be considered separate species.

Prior studies suggested that White-breasted Wood-Wrens could actually consist of several species, based on genetic differences. However, genetic differences alone do not necessarily mean that two populations could not interbreed. By adding in behavioral evidence (song recognition), the picture becomes clearer. The Cornell student researchers plan to submit their findings to the classification committee for South American birds, recommending that they consider the Amazon population of White-breasted Wood-Wrens a distinct species.

“The White-breasted Wood-Wren complex is really interesting and definitely deserves more research,” says Teresa Pegan, a Cornell senior at the time of the study and lead author of the resulting publication. “If we had been able to visit other sites in South America, it would have been fascinating to conduct reciprocal playback experiments. We found that White-breasted Wood-Wrens in Costa Rica don’t recognize the song of White-breasted Wood-Wrens from the Amazon. But would the wrens in the Amazon also fail to recognize the song of the Costa Rica birds as being the same species?”

The same question might be asked of dozens of other South American species with multiple populations evolving separately because of long geographical isolation. Other playback experiments like this one are under way to learn which subspecies have changed so much that they should be given full species status and a name of their own.

Reference

Teresa M. Pegan, Reid B. Rumelt, Sarah A. Dzielski, Mary Margaret Ferraro, Lauren E. Flesher, Nathaniel Young, Alexandra Class Freeman, Benjamin G. Freeman. Asymmetric response of Costa Rican White-Breasted Wood-Wrens (Henicorhina leucosticta) to vocalizations from allopatric populations. PLOS ONE. December 2015.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library