Conservation and the Arrival of Capitalism on the Plains of Hungary

By Gustave Axelson

January 15, 2013

To my American eyes, the great brown raptor circling high above an endless grassy expanse stretching all the way to the horizon might well have been a Golden Eagle. Except I wasn’t standing on the Great Plains, but in the great Carpathian Basin. I wasn’t on prairie but puszta. And that wasn’t a Golden Eagle but an Imperial Eagle, once the emblematic bird of the Hapsburgs and the Austro-Hungarian Empire—and perhaps emblematic again of Hungary’s proud and resurgent conservation movement.

Three decades ago, only 10 breeding pairs of Imperial Eagles were known to exist in Hungary, the last vestiges of a species disappearing in Eastern Europe. Today the population numbers about 150 nesting pairs, and they’ve spread out from their last refuges in the wooded foothills to the lowland plains they historically inhabited.

“Back in the old days, there were people guarding the nests,” said István Bártol, one of the guides for the week-long birding tour I was on, organized by Swarovski Optik last summer to showcase the abundant birdlife of Hungary. “The parks purchased the breeding areas to protect them. Imperial Eagles are one of our biggest successes.”

Hungary lies at an avian crossroads, near the eastern extent of many European species and the western edge of Eurasian birds with ranges that run across the steppes of central Asia. The tour group of 16 bird journalists and bloggers was a veritable NATO birding contingent, including four Brits, a Belgian, a Frenchman, a Spaniard, and three Americans. Some in our group had grown up during the Cold War and had always wondered what birds lay beyond the Iron Curtain. Now, just miles from the ruins of a Soviet military base, we trained our spotting scopes and binoculars skyward at the soaring eagle circling in grand arcs above the plain.

“This you would never see 20 years ago,” said Attila Steiner, the other Hungarian guide on this tour. He told me how Imperial Eagles benefited from a series of conservation measures that began in the early 1980s under the communist government, such as protecting the birds from shooting and poisoning. And now Hungary is continuing an ambitious program to install cross-arm insulation at every electrical tower in the country by 2020 to prevent eagle electrocutions. It’s a deeply devoted recovery effort, every bit as impressive as the one to save our own national symbol, the Bald Eagle.

Over the course of five days, Steiner and Bártol led our group to more impressive bird sightings, each one a further testament to the deep national tradition of bird conservation in Hungary.

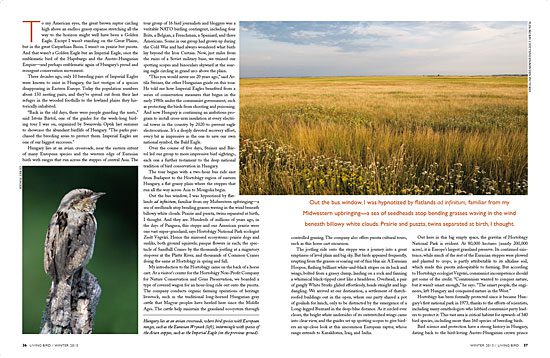

The tour began with a two-hour bus ride east from Budapest to the Hortobágy region of eastern Hungary, a flat grassy plain where the steppes that run all the way across Asia to Mongolia begin. Out the bus window, I was hypnotized by flatlands ad infinitum, familiar from my Midwestern upbringing—a sea of seedheads atop bending grasses waving in the wind beneath billowy white clouds. Prairie and puszta, twins separated at birth, I thought. And they are. Hundreds of millions of years ago, in the days of Pangaea, this steppe and our American prairie were one vast super-grassland, says Hortobágy National Park ecologist Zsolt Végvári. Hence the mirrored ecosystems: prairie dogs and susliks, both ground squirrels; pasque flowers in each; the spectacle of Sandhill Cranes by the thousands jostling at a migratory stopover at the Platte River, and thousands of Common Cranes doing the same at Hortobágy in spring and fall.

Our birding tour began on the puszta, the great plains of Eastern Hungary where begins a grassland biome that runs across the steppes of Central Asia. Photo by Gustave Axelson/Cornell Lab.

Hortobágy National Park, Europe's largest grassland preserve, offers horse-cart rides out onto the puszta. Photo by Gustave Axelson/Cornell Lab.

Puszta culture is similar to the frontier life of the American prairie: settlers eked out a subsistence lifestyle reliant on grazing livestock. Photo by Gustave Axelson/Cornell Lab.

Puszta settlers lived off their herds of Hungarian grey cattle—which are still used today to sustainably graze and maintain the grassland ecosystem. Photo by Gustave Axelson/Cornell Lab.

The grassy puszta also provides habitat for Red-footed Falcons, a near-threatened species in Europe. Photo by Dale Forbes, Swarovski Optik, with Swarovski ATX spotting scope.

The abundant insects of the puszta grasslands also provide food for colorful bee-eaters. Photo by Dale Forbes, Swarovski Optik, with Swarovski ATX spotting scope.

Lunch is provided at the turnaround point of the Hortobágy horse-cart ride. Photo by Gustave Axelson/Cornell Lab.

More grassland birding after lunch revealed Eurasian Hoopoes and Long-legged Buzzards. Photo by Gustave Axelson/Cornell Lab.

A Great Reed Warbler spotted in a puszta wetland is a perfect example of European warblers, drab in plumage but boisterous in voice. Photo by Corey Finger, 10,000 Birds, with Swarovski ATX spotting scope.

After Hortobágy, our tour headed off the puszta and into the Bükk mountains. Photo by Gustave Axelson/Cornell Lab.

In the village of Noszvaj, we stayed at the Nomad hotel, a family-run inn popular with birding tourists. Photo by Gustave Axelson/Cornell Lab.

Nine of Europe's 10 woodpecker species can be found in the Bükk region, owing to the abundance of fruit orchards, which attracted this Eurasian Wryneck. Photo by Corey Finger, 10,000 Birds, with Swarovski ATX spotting scope.

Eurasian Nuthatches also prowl the fruit trees for berries and seeds. Photo by Corey Finger, 10,000 Birds, with Swarovski ATX spotting scope.

And Red-backed Shrikes man the fence posts and help keep insect pest populations at bay. Photo by Corey Finger, 10,000 Birds, with Swarovski ATX spotting scope.

A hilltop in the village offers prime viewing for soaring raptors. Photo by Gustave Axelson/Cornell Lab.

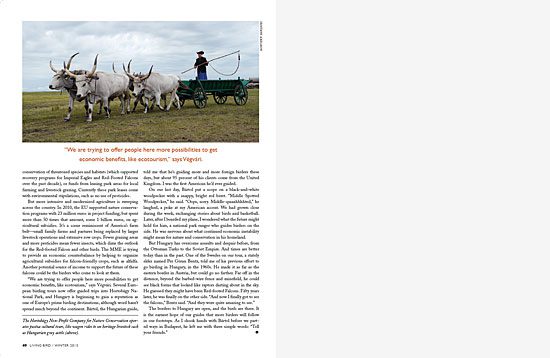

My introduction to the Hortobágy came on the back of a horse cart. At a visitor’s center for the Hortobágy Non-Profit Company for Nature Conservation and Gene Preservation, we boarded a type of covered wagon for an hour-long ride out onto the puszta. The company conducts organic farming operations of heritage livestock, such as the traditional long-horned Hungarian gray cattle that Magyar peoples have herded here since the Middle Ages. The cattle help maintain the grassland ecosystem through controlled grazing. The company also offers puszta cultural tours, such as this horse cart excursion.

The jostling ride onto the steppe was a journey into a great emptiness of level plain and big sky. But birds appeared frequently, erupting from the grasses or soaring out of thin blue air. A Eurasian Hoopoe, flashing brilliant white-and-black stripes on its back and wings, bolted from a grassy clump, landing on a rock and fanning a whimsical black-tipped crest like a headdress. Overhead, a pair of gangly White Storks glided effortlessly, heads straight and legs dangling. We arrived at our destination, a settlement of thatch-roofed buildings out in the open, where our party shared a pot of goulash for lunch, only to be distracted by the emergence of a Long-legged Buzzard in the deep-blue distance. As it circled ever closer, the bright white undersides of its outstretched wings came into clear view, and the guides set up spotting scopes to give birders an up-close look at this uncommon European raptor, whose range extends to Kazakhstan, Iraq, and India.

Out here in this big empty space, the gravitas of Hortobágy National Park is evident. At 80,000 hectares (nearly 200,000 acres), it is Europe’s largest grassland preserve. Its continued existence, while much of the rest of the Eurasian steppes were plowed and planted to crops, is partly attributable to its alkaline soil, which made this puszta inhospitable to farming. But according to Hortobágy ecologist Végvári, communist incompetence should get some of the credit. “Communism wanted to conquer nature, but it wasn’t smart enough,” he says. “The smart people, the engineers, left Hungary and conquered nature in the West.”

Hortobágy has been formally protected since it became Hungary’s first national park in 1973, thanks to the efforts of scientists, including many ornithologists who lobbied communist party leaders to protect it. This vast area is critical habitat for upwards of 340 bird species, including more than 160 species of breeding birds. Bird science and protection have a strong history in Hungary, dating back to the bird-loving Austro-Hungarian crown prince Rudolf von Habsburg, who organized the first International Ornithological Congress in 1884. Hungarians have been banding birds to study them since 1908, when the Hungarian Royal Ornithological Centre made international headlines with the discovery that a Hungarian White Stork had migrated to South Africa for the winter. A Hungarian professor once listed a short history of his country’s pioneering achievements as: “bloody revolution, the first underground metro… in Budapest, the Rubik’s cube, the demolishing of the Iron Curtain,… [and] the founding of a state ornithological institute.”

In 1974, a year after Hortobágy National Park was established, the Magyar Madártani ès Termèszetvèdelmi Egyesület (Hungarian Ornithological Conservation Organization) formed as the country’s first environmental group. The MME was one of the few sanctioned conservation entities under the communist regime, and it launched restoration programs for several endangered species, such as the Imperial Eagle, in the 1980s. After the political turnover in 1989, the MME was a voice for the strong conservation laws passed by the new parliament, which preserved Hungary’s natural resources, many of them unspoiled by communism, during the wave of mass land privatization in the 1990s. After Hungary joined the European Union in 2004, MME became a major implementer of EU-funded bird research and conservation projects as the country’s partner with BirdLife International.

“We Hungarians have always had conservation as part of our culture. We were less developed, we didn’t use pesticides in our farms, and so we have always had lots of insects, which was good for the birds,” said Steiner, the guide, as the horse-drawn cart bumped along the rutted puszta on our return trip. Swallows trailed in the cart’s wake like dolphins after a ship, swooping to snatch up the bugs disturbed by the wagon wheels.

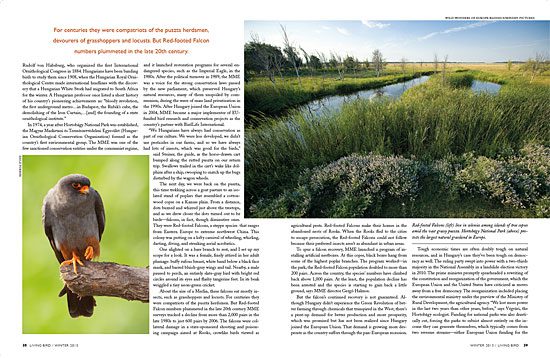

The next day, we were back on the puszta, this time trekking across a goat pasture to an isolated stand of poplars that resembled a cottonwood copse on a Kansas plain. From a distance, dots buzzed and whirred just above the treetops, and as we drew closer the dots turned out to be birds—falcons, in fact, though diminutive ones. They were Red-footed Falcons, a steppe species that ranges from Eastern Europe to extreme northwest China. This colony was putting on a lofty carnival of wheeling, whirling, darting, diving, and streaking aerial acrobatics.

One alighted on a bare branch to rest, and I set up my scope for a look. It was a female, finely attired in her adult plumage: buffy rufous breast, white band below a black face mask, and barred bluish-gray wings and tail. Nearby, a male paused to perch, an entirely slate-gray bird with bright red circles around its eyes and flashy tangerine feet. In its beak wriggled a tiny neon-green cricket.

About the size of a Merlin, these falcons eat mostly insects, such as grasshoppers and locusts. For centuries they were compatriots of the puszta herdsmen. But Red-footed Falcon numbers plummeted in the late 20th century. MME surveys tracked a decline from more than 2,000 pairs in the late 1980s to just 600 pairs by 2006. The falcons were collateral damage in a state-sponsored shooting and poisoning campaign aimed at Rooks, crowlike birds viewed as agricultural pests. Red-footed Falcons make their homes in the abandoned nests of Rooks. When the Rooks fled to the cities to escape persecution, the Red-footed Falcons could not follow because their preferred insects aren’t as abundant in urban areas.

To spur a falcon recovery, MME launched a program of installing artificial nestboxes. At this copse, black boxes hang from some of the highest poplar branches. The program worked—in the park, the Red-footed Falcon population doubled to more than 200 pairs. Across the country, the species’ numbers have climbed back above 1,000 pairs. At the least, the population decline has been arrested and the species is starting to gain back a little ground, says MME director Gergö Halmos.

But the falcon’s continued recovery is not guaranteed. Although Hungary didn’t experience the Green Revolution of better farming through chemicals that transpired in the West, there’s a pent-up demand for better production and more prosperity, which was promised but has not been realized since Hungary joined the European Union. That demand is growing more desperate as the country suffers through the pan-European recession. Tough economic times are often doubly tough on natural resources, and in Hungary’s case they’ve been tough on democracy as well. The ruling party swept into power with a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly in a landslide election victory in 2010. The prime minister promptly spearheaded a rewriting of the constitution and reorganization of the government, which the European Union and the United States have criticized as moves away from a free democracy. The reorganization included placing the environmental ministry under the purview of the Ministry of Rural Development, the agricultural agency. “We lost more power in the last two years than other years, before,” says Végvári, the Hortobágy ecologist. Funding for national parks was also drastically cut, forcing the parks to subsist almost entirely on the income they can generate themselves, which typically comes from two revenue streams—either European Union funding for the conservation of threatened species and habitats (which supported recovery programs for Imperial Eagles and Red-Footed Falcons over the past decade), or funds from leasing park areas for local farming and livestock grazing. Currently these park leases come with environmental stipulations, such as no use of pesticides.

But more intensive and modernized agriculture is sweeping across the country. In 2010, the EU supported nature conservation programs with 23 million euros in project funding, but spent more than 50 times that amount, some 1 billion euros, on agricultural subsidies. It’s a scene reminiscent of America’s farm belt—small family farms and pastures being replaced by larger livestock operations and extensive row crops. Fewer grazing areas and more pesticides mean fewer insects, which dims the outlook for the Red-footed Falcon and other birds. The MME is trying to provide an economic counterbalance by helping to organize agricultural subsidies for falcon-friendly crops, such as alfalfa. Another potential source of income to support the future of these falcons could be the birders who come to look at them.

“We are trying to offer people here more possibilities to get economic benefits, like ecotourism,” says Végvári. Several European birding tours now offer guided trips into Hortobágy National Park, and Hungary is beginning to gain a reputation as one of Europe’s prime birding destinations, although word hasn’t spread much beyond the continent. Bártol, the Hungarian guide, told me that he’s guiding more and more foreign birders these days, but about 95 percent of his clients come from the United Kingdom. I was the first American he’d ever guided.

On our last day, Bártol put a scope on a black-and-white woodpecker with a snappy, bright red beret. “Middle Spotted Woodpecker,” he said. “Oops, sorry. Middle-spaaahhhhted,” he laughed, a poke at my American accent. We had grown close during the week, exchanging stories about birds and basketball. Later, after I boarded my plane, I wondered what the future might hold for him, a national park ranger who guides birders on the side. He was nervous about what continued economic instability might mean for nature and conservation in his homeland.

But Hungary has overcome assaults and despair before, from the Ottoman Turks to the Soviet Empire. And times are better today than in the past. One of the Swedes on our tour, a stately elder named Per Göran Bentz, told me of his previous effort to go birding in Hungary, in the 1960s. He made it as far as the eastern border in Austria, but could go no farther. Far off in the distance, beyond the barbed-wire fence and minefield, he could see black forms that looked like raptors darting about in the sky. He guessed they might have been Red-footed Falcons. Fifty years later, he was finally on the other side. “And now I finally got to see the falcons,” Bentz said. “And they were quite amazing to see.”

The borders to Hungary are open, and the birds are there. It is the earnest hope of our guides that more birders will follow in our footsteps. As I shook hands with Bártol before we parted ways in Budapest, he left me with three simple words: “Tell your friends.”

About the Author

Gus Axelson is a science editor at the Cornell Lab.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library