Analysis: Losing the Law That Saves Migratory Birds

By Scott Weidensaul

September 18, 2020

From the Autumn 2020 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

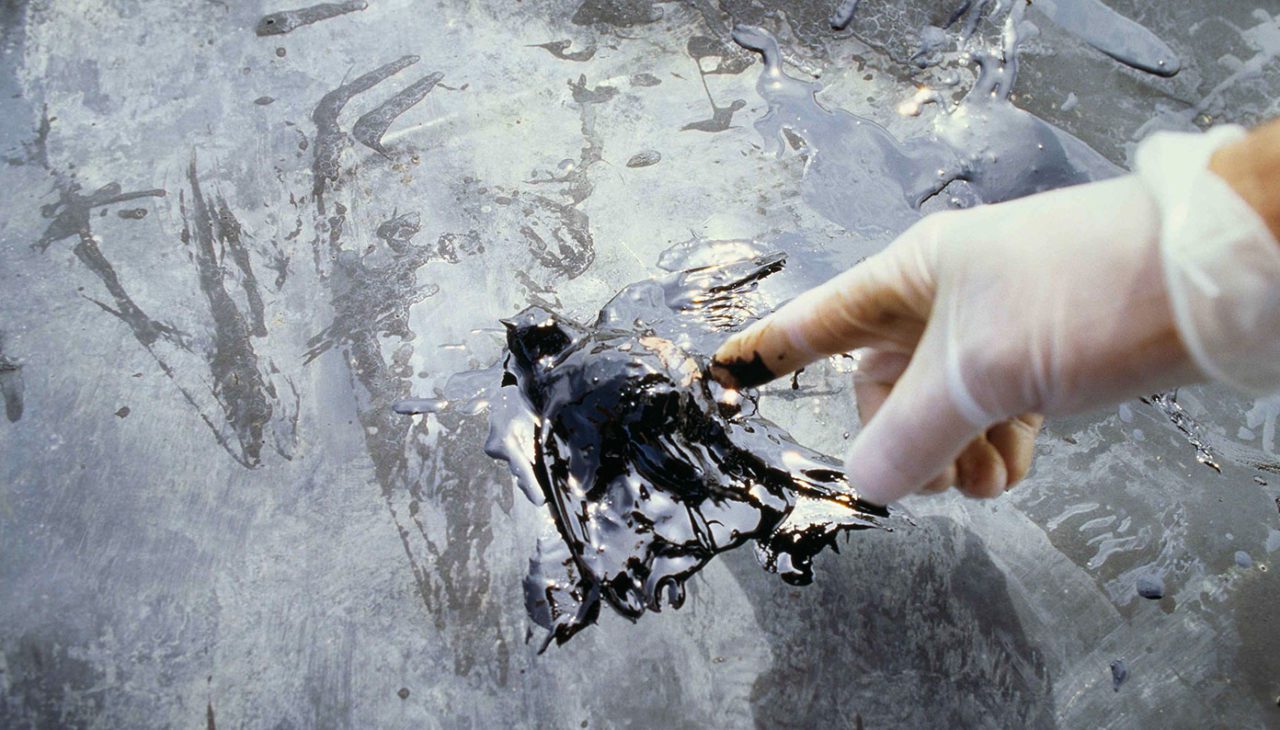

Ten years after the worst oil spill in American history, environmental watchdogs warn that the Trump Administration has significantly weakened many Obama-era regulations designed to prevent another such disaster. And the Administration has also gutted the enforcement power of the nation’s oldest bird-protection law, letting future polluters off the hook for bird deaths in a similar spill.

In May 2019, almost exactly nine years after the Deepwater Horizon explosion, the federal Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement announced sweeping changes to offshore drilling regulations, which the agency said would “ensure safety and environmental protection, while correcting errors and reducing certain unnecessary regulatory burdens imposed under the existing regulations.” Many of the changes were sought by the American Petroleum Institute, despite warnings from a bipartisan presidential commission in the wake of the Deepwater spill that API’s wish list would weaken oversight.

“The real strength of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act isn’t that it’s been used often in terms of litigation, but that it’s really powerful in getting industries on board to avoid that harm.

In December 2017, the Administration issued a legal opinion that incidental take does not fall under the purview of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act—the foundational federal law that protects wild birds. Instead, the Administration argued, only actions intended to kill birds should be prosecuted under the MBTA. Under that logic, BP would dodge the $100 million fine it paid for killing 1 million birds and violating the MBTA in the Deepwater accident, money that under law had to be used for bird restoration. In August 2020 a federal district court judge struck down the Administration’s legal opinion. Yet the Administration is pressing ahead to formally codify the removal of incidental take from the MBTA ahead of the November 2020 election, meaning industry would no longer be criminally liable if operations—even negligent ones—resulted in avoidable bird deaths.

Because most human-related bird mortality is unintentional, this new interpretation would effectively neuter the MBTA, according to Amanda Rodewald, senior director for conservation science at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Not only would it limit relatively rare prosecutions for egregious events like oil spills, she said, it would remove what has been a highly effective tool for nudging industry into correcting problems in advance, like reconfiguring utility poles to avoid electrocuting raptors, and covering oil sumps in which flocks of waterfowl become mired and die.

The changes “remove a powerful and effective incentive agencies have had in order to get industry to take proactive steps to reduce harm to birds,” Rodewald said. “We have a long history showing that the real strength of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act isn’t that it’s been used often in terms of litigation, but that it’s really powerful in getting industries on board to avoid that harm.”

Bird advocates are not taking the new legal interpretation lying down.

“It’s one of our top priorities to roll back that legal opinion, whether it’s through advocacy efforts with the Administration or through legislative avenues,” said Karen Hyun, vice president for coastal conservation at the National Audubon Society.

One such legislative avenue is the Migratory Bird Protection Act, a bill first introduced into the U.S. Congress in 2019, and now, with bipartisan support from 96 cosponsors. The bill “affirm[s] that the Migratory Bird Treaty Act’s prohibition on the unauthorized take or killing of migratory birds includes incidental take by commercial activities,” and would restore the MBTA’s enforcement powers. It was voted out of committee in January, but as of press time the bill hasn’t been taken up by the full House of Representatives.

A spokesperson for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which proposed the controversial new interpretation, responded to questions about the rule change by saying it provided “legal clarity and certainty.” A variety of other federal laws, the spokesperson said, including the Oil Pollution Act, Endangered Species Act, and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, “still apply to the protections of publicly held natural resources, including migratory birds.” The spokesperson also said that the agency “will continue to work with our industry partners to minimize impacts on migratory birds.”

There was a reason, Hyun said, that the Department of Justice used the MBTA after the BP spill (and after many other such disasters) in addition to other federal laws.

The Act “has provided direct and criminal accountability for negligent actions that have killed substantial numbers of birds, which other laws do not provide,” she said. “Those penalties then directly benefit birds impacted by the spills by distributing them through the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund.”

Hyun noted that the USFWS, in its own draft environmental impact statement justifying the reinterpretation, acknowledged that the MBTA fine from the BP spill “protected and restored several hundred thousand acres of priority wetland habitat for the conservation of migratory birds.”

“This could not have happened under their new and unprecedented interpretation,” Hyun said.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library