Analysis: If Another Deepwater Horizon Happens, New Policy Changes Would Give Polluters a Free Pass

By Amanda Rodewald

September 16, 2020

From the Autumn 2020 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Birds have never needed the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service more. According to the 2016 State of the Birds report, over one-third of North America’s nearly 1,200 bird species need urgent conservation action. And just last year, an international team of scientists from seven institutions (including the Cornell Lab of Ornithology) reported in the journal Science that North American bird populations have declined by almost 3 billion birds since 1970.

Normally we would look to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to help address this crisis of bird declines. After all, the mission of the USFWS is “to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, plants, and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people.” (Emphasis added is mine.)

Yet our federal government has deliberately undermined the authority of the USFWS to protect birds by neutering the 102-year-old Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Since enacted, the MBTA had prohibited incidental take—activities that unintentionally harm birds, but show negligence such that the harm could have been avoided. (For example, the entirely preventable Deepwater Horizon oil well blowout killed more than 1 million birds and triggered $100 million in penalties under the Act.) In December 2017, the Administration issued a legal opinion that removed incidental take from MBTA prosecutions.

In August 2020, a federal district court judge struck down that legal opinion. And yet, the Administration is still in the final stages of codifying that exclusion of incidental take from the MBTA. This exclusion both renders the Act powerless to protect birds from most direct sources of human-caused mortality and eliminates a powerful incentive for industry to proactively reduce or avoid harm to birds.

Industry-associated harm to birds is substantial. Industry alone kills from 453 million to 1.1 billion birds annually, with a range of mortality sources including poisoning (72 million birds), electrocution or collisions with power lines (more than 28 million birds), oil pits (750,000 birds), and wind turbines (more than 573,000 birds).

Given this mortality, removing incidental take is a big problem. For starters, bird populations in North America are declining due to numerous threats, and the urgency is real. We’ve lost about 30% of North American birds across nearly all regions, habitats, and avian families. Grassland bird populations are down by 53%, shorebirds by 37%, boreal forest birds and aerial insectivores by 32% each, and migratory birds by 28%. More worrisome still is that these steep declines are evident among common and beloved birds, like Chimney Swift, Eastern Meadowlark, Blackpoll Warbler, Pine Siskin, Varied Thrush, Grasshopper Sparrow, and Barn Swallow.

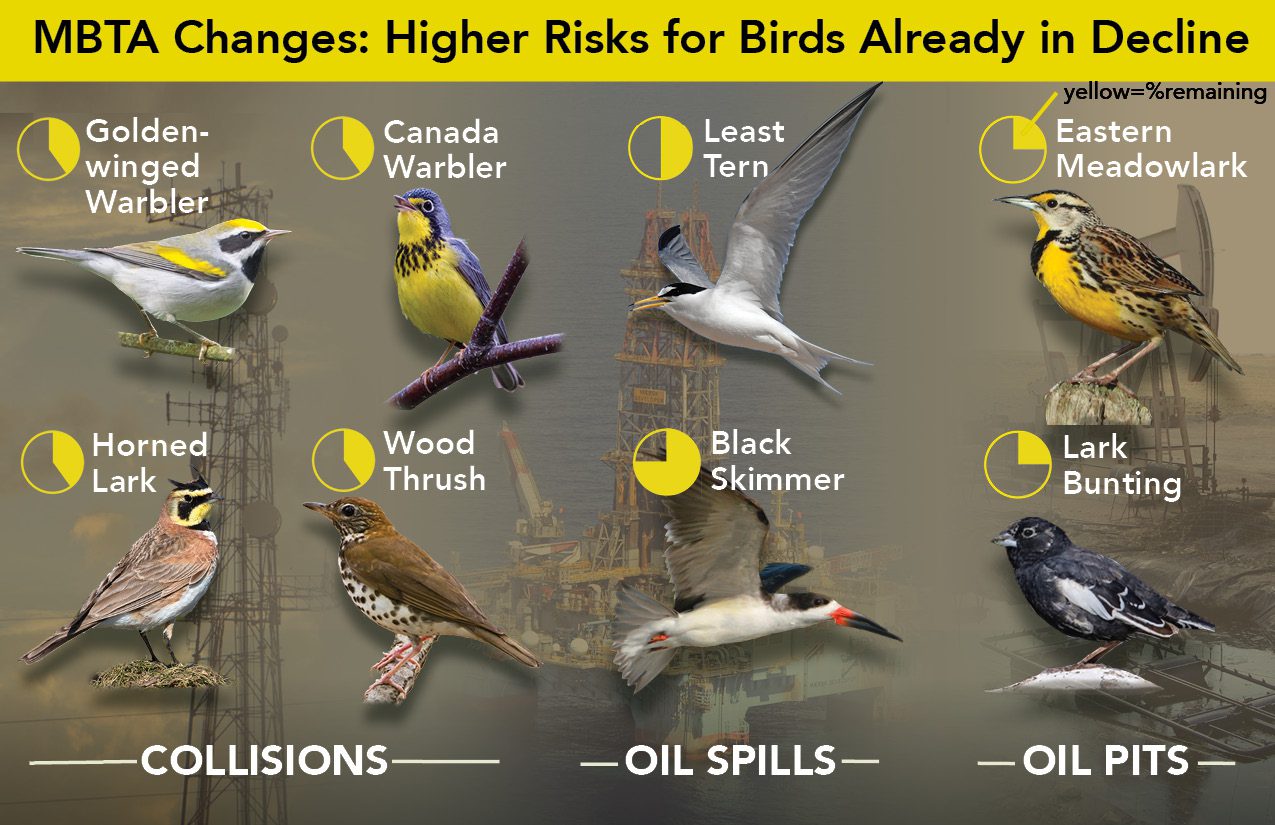

Already, industrial activities can disproportionately affect species of conservation concern. More than 80 of the 172 bird species reported to be killed in oil pits are in steep population decline, including Northern Bobwhite, Eastern and Western Meadowlark, and Lark Bunting—all of which have already lost 75% of their populations. More than 50 of the 350 species of Neotropical migratory songbirds are vulnerable to collisions with tall structures, including American Kestrel, Wood Thrush, Purple Finch, Horned Lark, and Golden-winged, Canada, and Kentucky Warblers. Oil spills, like the Deepwater Horizon disaster, heavily impact declining seabirds, including Least and Black Tern and Black Skimmer. These examples represent only a few of the many bird species that are in steep decline and expected to be further harmed by industry activities, should incidental take be permanently excluded from the MBTA.

The process of codifying the exclusion of incidental take from the MBTA requires a formal analysis of the potential environmental impacts of doing so, as compared to other courses of action. The USFWS acknowledged in this analysis—a draft Environmental Impact Statement released in June 2020—that excluding incidental take is indeed expected to worsen bird declines and negatively impact vulnerable species, potentially to the point of requiring more birds to be listed under the Endangered Species Act.

Much of the increased threat to birds will likely stem from the loss of what was a powerful incentive for industry to take proactive steps to reduce harm to birds. The effectiveness of this incentive is well established. For instance, the MBTA was used by the Nixon Administration to convince power companies to increase the distance between power lines in order to avoid bird electrocutions. The MBTA motivated the Federal Aviation Administration to require new blinking lights and marking standards on tall communication towers to reduce the risk of impacts to migratory birds. It also provided strong leverage to prod energy companies to cover oil pits with nets or employ alternative approaches to exclude birds from the pits.

If industries no longer fear violating the MBTA, they will be less likely to implement best practices and standards to avoid killing birds. On this point, the USFWS draft EIS is clear.

Elsewhere in the draft EIS, the agency suggested that the MBTA may be redundant, because there are other legal mechanisms that protect birds. Although laws like the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act have the potential to support bird conservation, they apply to far fewer species and situations than the current MBTA. (For example, around 100 bird species are covered under the ESA, whereas the MBTA applies to about 1,100 species.) What’s more—the Administration is actively working to weaken those laws, too.

The loose patchwork of state migratory bird protections is unlikely to save the day either, as the draft EIS notes that state agencies typically rely on the USFWS for investigations and enforcement. Now more than ever, few state agencies have sufficient human or fiscal resources to pick up the slack were the USFWS to shift responsibilities for investigating bird kills to states.

The science is clear—we should be doing more, not less, to protect birds. The exclusion of incidental take from the MBTA silences the Act on most sources of mortality for migratory birds and eliminates a powerful incentive for operators to proactively mitigate harm to birds. Not only does this change fundamentally weaken the protections our nation has granted to birds, it also dismisses commitments to our international treaty and undermines the broader benefits of birds to American society.

Amanda D. Rodewald is the Garvin Professor and codirector of the Center for Avian Population Studies at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, faculty in the Department of Natural Resources at Cornell University, and faculty fellow at Cornell’s Atkinson Center for Sustainability.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library