A New Flyway: Fall Migrants Cross the Atlantic to Reach South America

By Pat Leonard

From the Autumn 2015 issue of Living Bird magazine.

October 7, 2015

Imagine that you’re a Blackpoll Warbler, weighing barely as much as two U.S. quarters. It’s September, so you’re stuffing yourself with insects and fruit in the eastern boreal forest of Canada, nearly doubling your weight for an epic journey. As the food dwindles—between now and mid-October, when the weather is right— it’s time to go. Launching from the northeastern coast of North America, you head over the Atlantic Ocean, flying nonstop for 2 or 3 days, covering 1,500 to 2,200 miles en route to northern South America. If storms move in, you may be forced down on Bermuda or another island—if you’re lucky. But no matter how tired you are, you can’t take a rest over the open ocean. If you stop flapping your wings, you’ll plunge into the sea and die.

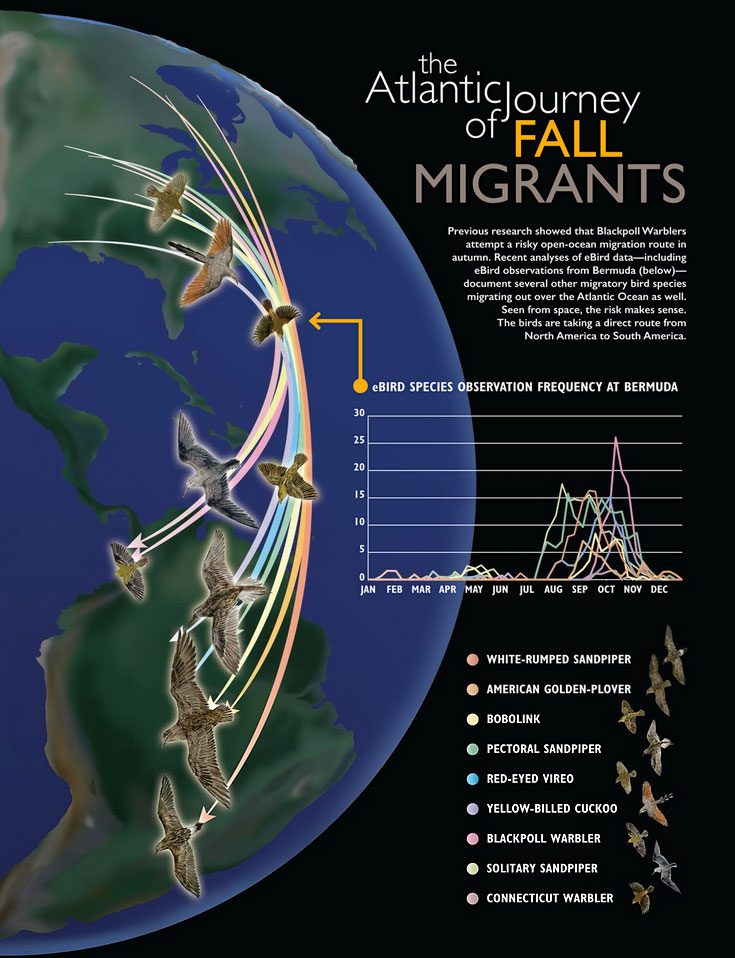

The Blackpoll Warbler’s amazing transoceanic journey made national headlines earlier this year. In March, University of Massachusetts ecologist William DeLuca and coauthors published a study in which they used tiny geolocators to prove that the birds’ eastern boreal forest population was indeed traversing long distances over the Atlantic during fall migration. But it turns out that the Blackpoll Warbler is not alone. New research using eBird data and weather radar is documenting several other species that also take this risky route on their southbound journeys.

Following small birds during migration used to be impossible. There are few observers to spot them as they fly over the ocean, and earlier tracking tags were too heavy for small birds. That’s changing now.

“With geolocators we learn much more than just the route,” says Marshall Iliff, coleader of eBird. “We get data on the duration and location of stopovers and wintering areas, plus connectivity between breeding, stopover, and wintering sites.”

One drawback to geolocators is the need to recover tagged birds to download the data. Recapturing warblers is tricky, so data often come from just a few individuals.

Data from birders is helping to fill in the gaps. For example, Cornell Lab researcher Frank La Sorte analyzed 6 million eBird observations and saw migratory patterns for a number of other species that, like the Blackpoll Warbler, fly the Atlantic route in fall. These other trans-Atlantic migrants include Bobolink, Yellow and Black-billed cuckoos, Connecticut and Cape May warblers, Bicknell’s Thrush, and American Golden-Plover. Some cross the Atlantic in fall and the Gulf of Mexico in spring, making long open-water treks on both legs of their migration.

“It’s a tremendously risky strategy,” says La Sorte. “For populations of these species to persist there has to be a benefit to transoceanic migration. Some would argue that flying over the ocean is actually safer—no predators, no pathogens, no buildings. You just can’t land.” By striking out over the Atlantic in autumn, birds take advantage of weaker headwinds and get an assist from the northeast trade winds as they move farther south. Taking a more direct route may also get them to their destination sooner.

eBird data show that Bermuda, Cuba, and other islands play an important role as rest stops during trans-Atlantic migrations. For example, eBird reports of Blackpoll Warblers, Bobolinks, and other trans-Atlantic migrants on Bermuda are very low during most of the year (see chart at right). But starting in late August these reports spike, then disappear again after October—just the pattern to be expected from species with migratory routes going over the ocean.

Cornell Lab researcher Andrew Farnsworth is also trying to better define the trajectories of various species migrating over the Atlantic by identifying the clouds of birds visible in radar imagery at weather stations from Maine to Virginia.

“Radar is great for pinpointing where migratory flights begin, how many birds are aloft, in what direction and speed they are moving, and at what altitudes,” says Farnsworth. His research so far has indicated that the Boston area may be a hotspot for birds making the jump off the coast to migrate over the ocean.

Knowing the specific sites birds use on migration and how long they use them is vital for targeted habitat conservation.

“There is still a tremendous amount we don’t know about bird migration, especially transoceanic flights,” says Cornell Lab researcher Ken Rosenberg, “but finding ways to incorporate the data we gather over multiple channels into migration models that can inform conservation strategies is an exciting new area of research.”

And, beyond the gee-whiz technology, we are awed yet again by the endurance of these small bundles of feathers as they make their do-or-die journeys southward each fall.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library