Sandpiper or plover? Or both? A field report from Chile [Video]

By Andy Johnson, Cornell student April 10, 2012

The enigmatic Diademed Sandpiper-Plover lives high in the Andes. Photo by Andy Johnson.

Photo by Andy Johnson.

Gray-hooded Sierra-Finches sang frequently from low rocks. Photo by Andy Johnson.

Fog rolls down the Yeso Valley in the afternoon. Photo by Andy Johnson.

Diademed Sandpiper-Plovers look for food in both bogs and streambeds. Photo by Andy Johnson.

A White-browed Ground-Tyrant takes a break from running. Photo by Andy Johnson.

A Black-billed Shrike-Tyrant surveys the lower Yeso Valley. Photo by Andy Johnson.

As sunlight drained out of the day, the sides of the Yeso Valley lit up. Photo by Andy Johnson.

On a late January evening, the sun drew its last sharp rays across the peaks encircling the Yeso Valley, and Andean Condors made their day’s last rounds. At over 8,000 feet of elevation, our alpine campsite was nestled among snow-covered peaks, some of which reached another 8,000 feet higher still.

We were just a few hours’ drive east of Chile’s smoggy capital, Santiago. But it felt a world away, because we were here to seek the company of one of the world’s most enigmatic shorebirds, the Diademed Sandpiper-Plover (Phegornis mitchelli). A small bird of muted brown and red, with a finely barred breast and bright-yellow legs, the sandpiper-plover is named for a striking white ring that adorns its dark head.

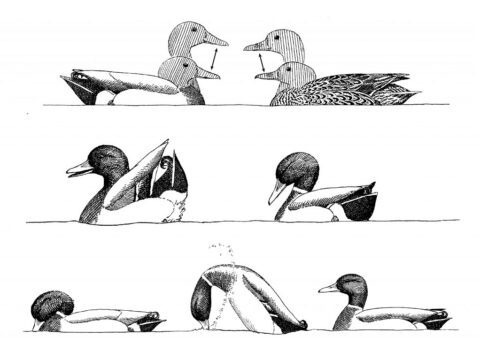

In the few days I watched them, they were often in loose pairs, probing montane streambeds and bogs with their peculiar long bills, and they frequently paused atop a cushion plant or rock, suddenly dipping their bodies forward every few seconds in a motion opposite that of a typical plover. These singular birds held a charisma that truly set them apart, in part born of their precarious existence.

The Diademed Sandpiper-Plover is considered near-threatened due to its small and declining global population and restricted range: a few high-elevation sites of peat bog and alluvium in the Andes. Our lack of knowledge about the basic ecology of this species greatly compounds its vulnerability, and that’s what brought Jim Johnson, an Alaskan shorebird expert, and Andrea Contreras, a Chilean graduate student, to the Yeso Valley. I tagged along as part of an undergraduate expedition from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology to collect high-definition video and audio.

The study had begun only a year earlier, in January 2011, when the austral summer spares the Yeso Valley from constant snow and wind. Johnson and Contreras wanted to learn what makes for good sandpiper-plover habitat. The birds live exclusively in high-elevation bogs among cushion plants and shallow streambeds, but they’re true connoisseurs, shunning many bogs that a human observer would deem suitable. It was surprising then, to find the birds nesting on dry, grassy mounds, dozens of meters from running water, as well as on small, stony islands in the midst of rushing streams.

So there’s more at play in this system than the plant communities and geology that meet the eye. What is causing this species’ decline, and why are they absent from other habitats that seem suitable? Andrea, Jim, and their crew are here to gradually chip away at this enigma.

Earlier that day, we had awoken amidst ground-tyrants, earthcreepers, hillstars, cinclodes and condors—a menagerie of high-elevation specialists. And there we were, contained as an infinitesimal part of the rest, within this most stunning fishbowl between mountains: the Yeso Valley. The peaks towered over us in their apparent permanence, reminding me that all I’ve ever known is contained within a mere snapshot of time. Of course, this snapshot I was living in had another 12 hours of daylight, and we were here to make the most of it—to film the Diademed Sandpiper-Plover and its neighbors.

Our crew dispersed throughout the valley, revisiting productive sites from the 2011 season in hopes of finding banded birds and new nests. One of the first birds we encountered was kind enough to lead us to its two splotchy brown eggs nestled atop a small, grassy mound. On other territories, adults herded chicks on wobbly legs across the wet meadows, and on still others fledged young were already foraging beside their parents.

This broad range in the breeding progression of this single species, in this single valley, suggests that pairs raise multiple broods in a year. But even this crucial population information remains a mystery. We banded chicks and adults with unique color combinations, which would allow the team to assess these and other crucial life history data, such as life expectancy, site fidelity, and chick survival rates in subsequent seasons.

As of yet, even the birds’ seasonal movements remain uncharted. Some sightings suggest they may overwinter in high Andean passes, enduring weather unlike almost any other shorebird. A survey of the Yeso Valley this winter (in June) aims to answer that question as well. If the birds turn out to be nonmigratory, it would mean these small populations along the spine of the Andes are isolated from one another and could suggest an even more precarious existence.

Throughout the remainder of our all-too-brief stay we filmed diverse parts of their life histories: adults calling, foraging, incubating nests, brooding chicks, and accompanying fledglings. In the week after following our departure, Andrea, Jim and their team went on to find an impressive 18 nests. The crew’s research is just beginning, but already they’re unraveling mysteries whose answers will inform the preservation of this remarkable denizen of the high Andes.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library