Red-tailed Hawk Fledglings Face Invisible Challenges

August 12, 2022On a clear morning in late June, 80 feet above Cornell University’s campus, the youngest of the Cornell Red-tailed Hawks tightroped the railing of its nest. Viewers of the Cornell Hawks cam watched with apprehension, then anticipation as the hawk stopped and gripped the ledge. Wings raised, feathers fluttering, bright eyes scouting the campus skyline, the young hawk decisively launched into the air, fledging into adulthood to brave a novel landscape with novice wings.

Fledging is just the first leap this young hawk takes in navigating the hurdles of life outside the nest. Along with developing its hunting and flying skills, it is also discovering a complex campus environment where natural features blend with human construction, an obstacle course that can quickly become dangerous—especially for inexperienced fliers.

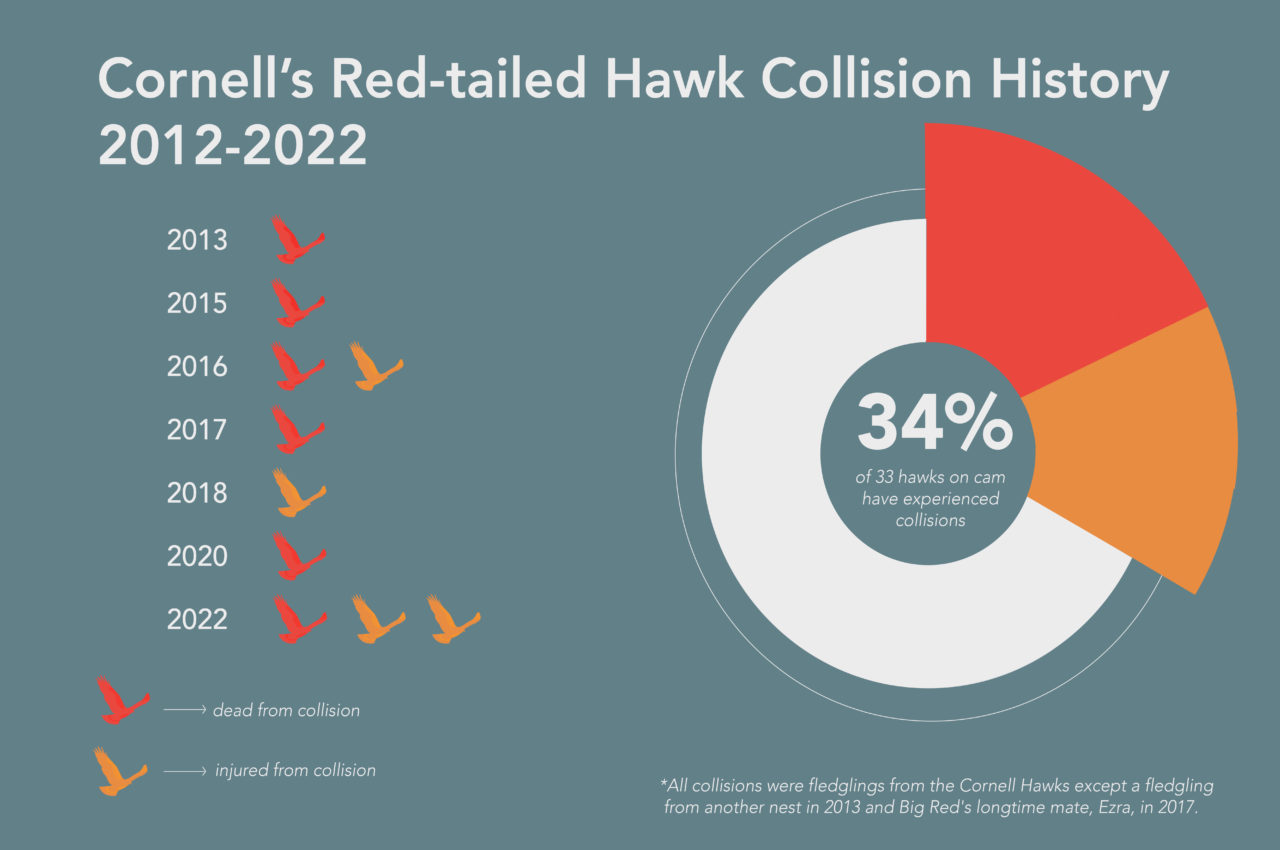

Having witnessed multiple injuries and deaths of fledglings over the years, long-time viewers of the cam are well aware of the hazards that await the hawks at every turn. In most years, one or more hawks have been found dead or injured from collisions on campus.

Ultimately, in the 11 years we’ve followed the Cornell Hawks, there were only four seasons where no collision-induced injuries or fatalities were recorded. And although there is some degree of uncertainty surrounding a few of the incidents, the nature of the injuries, strong circumstantial evidence (e.g oily impressions, feathers stuck to the glass), and the locations where the birds were found all indicate collisions as the most likely cause.

The hawks’ nest and the viewing community are fortunate to have dedicated volunteers watching the fledglings and the available resources for rehabilitation. But while this particular nest may be an anomaly in terms of how closely it is monitored, by no means is it the only one affected by collisions: each year in the United States alone, up to one billion birds are estimated to die from collisions—the majority from window strikes. However, unlike Cornell’s hawk family, there are millions of collision survivors who can’t be whisked off to a nearby wildlife hospital, and millions more fatalities that go unrecognized and unrecorded.

A window strike is fatal irony, the visibility of sky and landscape reflected in glass an invitation to invisible tragedy for birds. Birds often perceive windows as extensions of their habitat, whether they see the reflection of foliage, an indoor plant, or the environment on the other side of the building.

While the thought of millions of birds thudding into windows across the United States is certainly disturbing, what may be equally unsettling is the fact that most of these collisions go unnoticed—after all, the strike is but an instant. The birds either flit away unscathed or their grounded bodies are later plucked by a predator.

Luckily, there’s good news: such a staggering statistic presents an enormous opportunity to increase worldwide bird populations. Unlike many other large-scale and complex threats birds face today (like habitat loss and global warming), individual action to prevent window strikes can save birds immediately, the positive repercussions of which will last for years.

The hawks are evidence of tangible action arising from tragedy. Though grim and heartbreaking, the recurring pattern of injuries and deaths due to collisions has catalyzed action and inspired further conversation at Cornell (see sidebar, “Making the invisible visible”) and within the viewing community.

As one viewer commented, “With the death of G3, everyone started researching bird strikes and options to prevent them.” Enacting preventative measures at home is not only possible, but crucial; it’s estimated that 44% of window strikes are caused by residential buildings.

To help make your windows more bird-friendly you can install Acopian BirdSavers (vertical cords outside the window spaced a few inches apart), affix bird tape, or use washable tempera paint to create your own bird-inspired designs. Studies have also found indirect actions to be effective supplements. For example, migrating birds are attracted to lights at night, so turning off unnecessary lights keeps them safer on their journeys. Relocating your bird feeders can also reduce the chance of a collision. (For more details on how to prevent collisions at home click here.)

If you choose to apply treatments like stickers or tape, make sure the glass is uniformly covered with objects spaced no more than 2-3 inches apart. Research has proven such measures, when implemented with the recommended spacing, result in a measurable reduction of bird strikes. A 2013 study found that cords spaced 10.8 cm apart (4.3 in) resulted in 11 out of 12 birds moving to avoid the treated window, while cords spaced 8.9 cm apart (3.5 in) resulted in 10 out of 10 birds avoiding it.

Such treatments can even surpass their intended purpose, fostering creativity and inspiring further conversation. For example, the University of British Columbia patterned the windows of their bookstore with favorite quotes from professors and students, alerting birds to the glass while also serving as a point of community engagement. Another building on UBC’s campus features a living screen (a mesh screen covered in vines) that acts as a barrier to reduce collisions and provides food and habitat for urban birds.

Regardless of their complexity or creativity, solutions implemented across the individual and institutional levels could spare millions of birds from fatal strikes—including those witnessed year after year at the hawks’ nest.

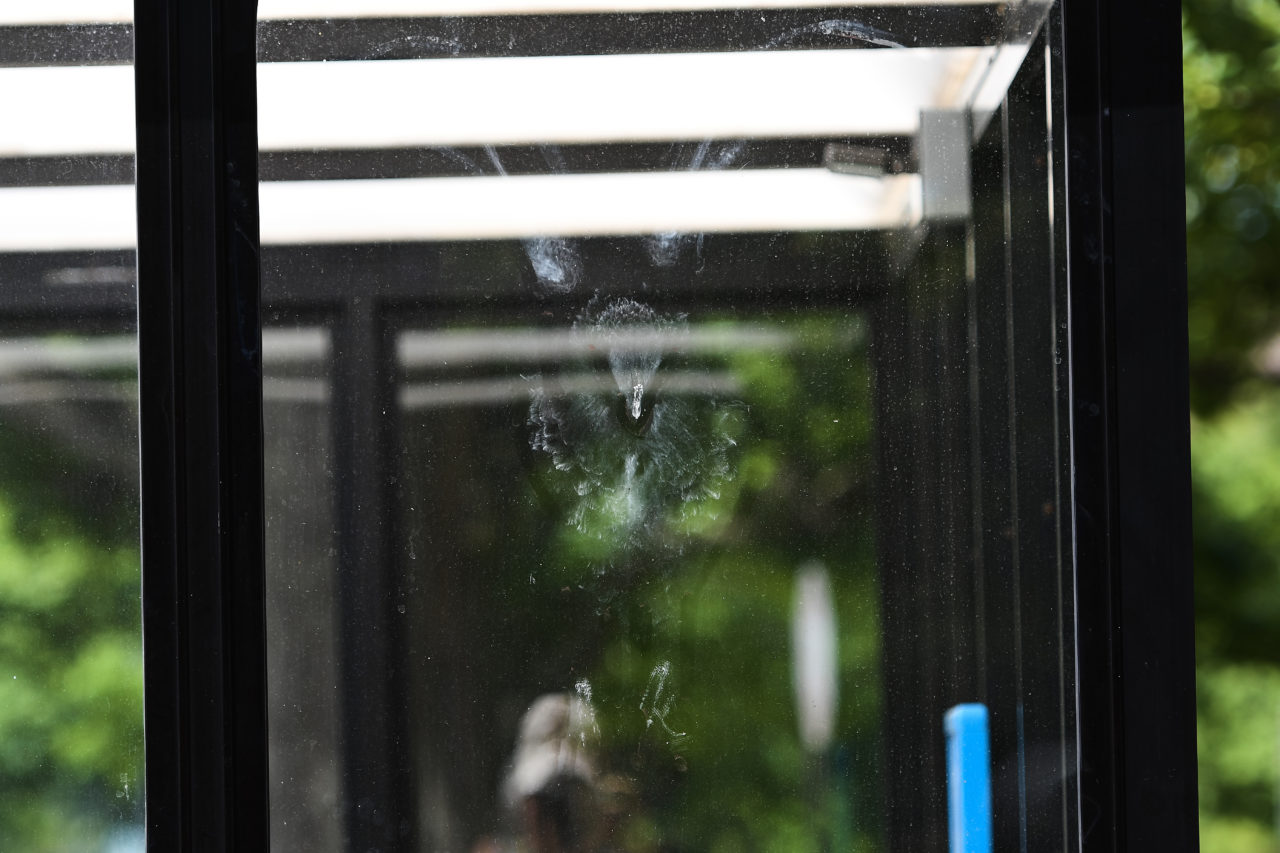

In 2016, the young hawk that collided with a bus shelter left behind a ghostly imprint, a few of its feathers clinging to the glass. We had watched that hawk grow, develop, and learn from the time it was a cottony fluffball to a weapon-wielding raptor—all for its life to be reduced to a smudge. As quickly as it had fledged, it fell.

Even this season wasn’t spared, a shocking three out of four fledglings succumbing to collisions: L3 sustained a fractured wing; L4 a bruised and swollen wing at the carpus (or “wrist”), and eldest fledgling L1 was found dead from a fatal collision outside Stocking Hall. Though L4 was successfully released near campus in late September, this season’s unprecedented number of collisions renewed the heartbreak felt by the viewing community and accelerated existing efforts across campus to make the hawks’ territory as safe as possible.

When considering the birds that die from collisions every year— each bird with a unique story that comes to the same, unceremonious end—the almost incomprehensible enormity of ‘one billion’ becomes much more real. Compared to other issues flocks face today, reducing collisions entails simple, accessible solutions that would help our neighborhood birds navigate safer environments and keep one billion birds alive and up in the sky.

Ellie VanHouten is a sophomore at Cornell University. Her work on this story as a student editorial assistant was made possible by a Cornell Lab of Ornithology Experiential Learning Grant.

Reference:

Klem, Daniel, and Peter G. Saenger. 2013. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Select Visual Signals to Prevent Bird-Window Collisions.” The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 125 (2): 406–11.

Bird Cams is a free resource

providing a virtual window into the natural world

of birds and funded by donors like you

Pileated Woodpecker by Lin McGrew / Macaulay Library