Who Wins at the Bird Feeder—the Lone Wolf or the Social Butterfly?

Five years after an illuminating study on bird-feeder dominance hierarchies, a new crop of research is delving into what causes conflicts at the seed station.

January 4, 2024

From the Winter 2024 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

When hordes of chickadees, finches, and woodpeckers descend on a backyard bird feeder, squabbles are bound to erupt: Sometimes getting a choice morsel means muscling your way into position.

Minimizing conflict in these situations is good for birds, says Cornell Lab of Ornithology Research Associate Eliot Miller: “It takes energy to fight, and it can be dangerous, so it usually makes sense to avoid it.”

In 2017, a team led by Miller used Project FeederWatch data to analyze such conflicts—moments when one bird displaces another at a food source. The results, published in the journal Behavioral Ecology, gave rise to a dominance-hierarchy ranking for backyard birds: a guide to which species were most likely to hold their ground in one-on-one confrontations with other species, and which ones were more likely to turn tail and fly.

Now, other scientists are picking up where Miller left off, using an ever-growing set of FeederWatch data to dive deeper into the behaviors, social relationships, and physical traits that shape conflict at the bird feeder.

Biologist Roslyn Dakin of Carleton University in Canada was inspired by Miller’s 2017 study to look into whether a bird’s social tendencies affect their place in the pecking order. For example, some birds, such as finches and House Sparrows, are social butterflies that often visit feeders in groups, while others, such as woodpeckers and nuthatches, are more likely to be lone wolves.

Working with Carleton PhD student Ilias Berberi, Dakin analyzed 6.1 million FeederWatch observations to determine the average group size at feeders for 68 species.

“What we realized once we got into [the FeederWatch data] is that it actually presents all kinds of opportunities that we don’t have otherwise,” says Dakin. “It lets us ask questions that we couldn’t possibly ask through the observations of any one scientist or even a small team of scientists because no one person could observe communities across an entire continent.”

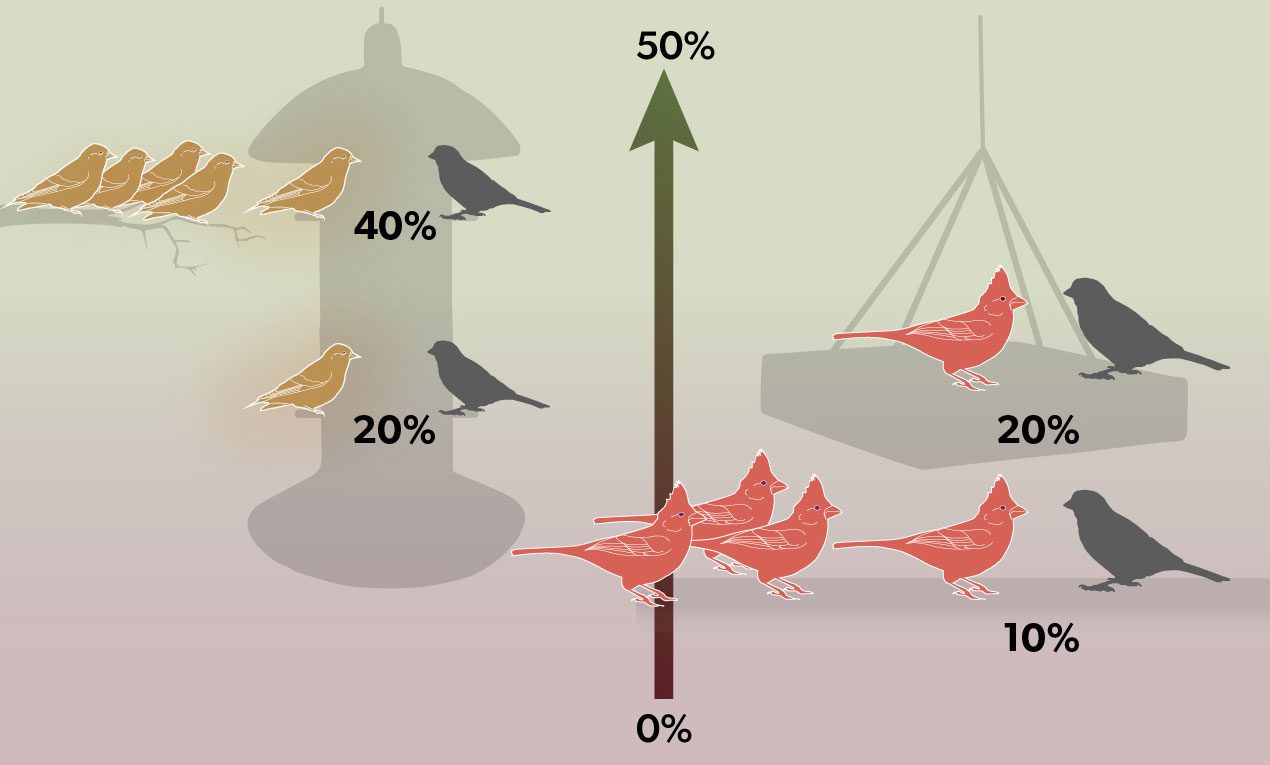

Next the team looked into 55,000 recorded one-on-one dominance interactions in the FeederWatch dataset to see if the loner birds or social birds are better at displacing other birds. Their results, published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B in February 2023, showed that birds like White-breasted Nuthatch and Red-bellied Woodpecker (lone wolves that were among the least social birds in the study) were also among the most likely to displace others. At the other end of the spectrum, the social butterflies that usually visited feeders in groups, such as American Goldfinches and House Sparrows, were most likely to flee the scene when facing off against a foe of similar stature.

But there was a caveat: When these socially inclined birds came to feed in groups, their performance improved. For example, highly social Pine Siskins lose most encounters when they are alone, but when a group of five visits together their individual interactions, on average, become twice as successful.

Conversely, some birds that tend to be lone wolves, like Northern Cardinals, became less successful in feeder showdowns when they visited in groups.

“We think that these effects might be driven by what the birds are paying attention to,” says Dakin. “So maybe when cardinals are there in a group, they’re paying attention to each other and might be more prone to being displaced by a different species.”

Another study, published in 2024 in the journal Nature Communications and led by Gavin Leighton, an assistant professor of biology at Buffalo State University, investigated what happens to the dominance hierarchy when a new face shows up at the bird feeder. Leighton and his team looked at around 1,600 interactions from more than 100 different bird species in the FeederWatch data and determined that “syntopic” species—pairs of species that usually overlap in space and time—get into fights less than expected. On the other hand, species that are not often found together fight more than expected when their paths cross.

For example, chickadees, goldfinches, and juncos seem to avoid getting into scuffles even though they’re often shoulder to shoulder at feeders. On the other hand, chickadees seem to be spoiling for a fight with Yellow-rumped Warblers.

“It all comes down to energy,” says Leighton. “You don’t want to get into fights you know you’ll lose. When birds see each other on a regular basis, they’re more likely to know whether they are the subordinate one or the dominant one. If you are in close proximity to someone you know is likely to beat you, it’s more advantageous to just leave before anything happens.”

Both Dakin and Leighton are continuing to use FeederWatch data to tease apart the social networks at bird feeders. Leighton is currently studying whether harsh weather makes it more likely that a subordinate species will resist in an attack; Dakin is interested in how weather affects group size at bird feeders.

Emma Greig, the project leader for FeederWatch at the Cornell Lab, says she’s thrilled the data is being used in new ways, and that thousands of FeederWatchers are continuing to report dominance interactions in their observations.

“We can use bird counts to infer things about behavior, but now we can also use people’s direct observations of behavioral interactions to learn how birds relate to one another,” says Greig. “It’s really fantastic data.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library