The Secret to Starling Success: It’s in Their Genes

By Pat Leonard

European Starling in Ohio by Matthew Plante/Macaulay Library. March 29, 2021From the Spring 2021 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

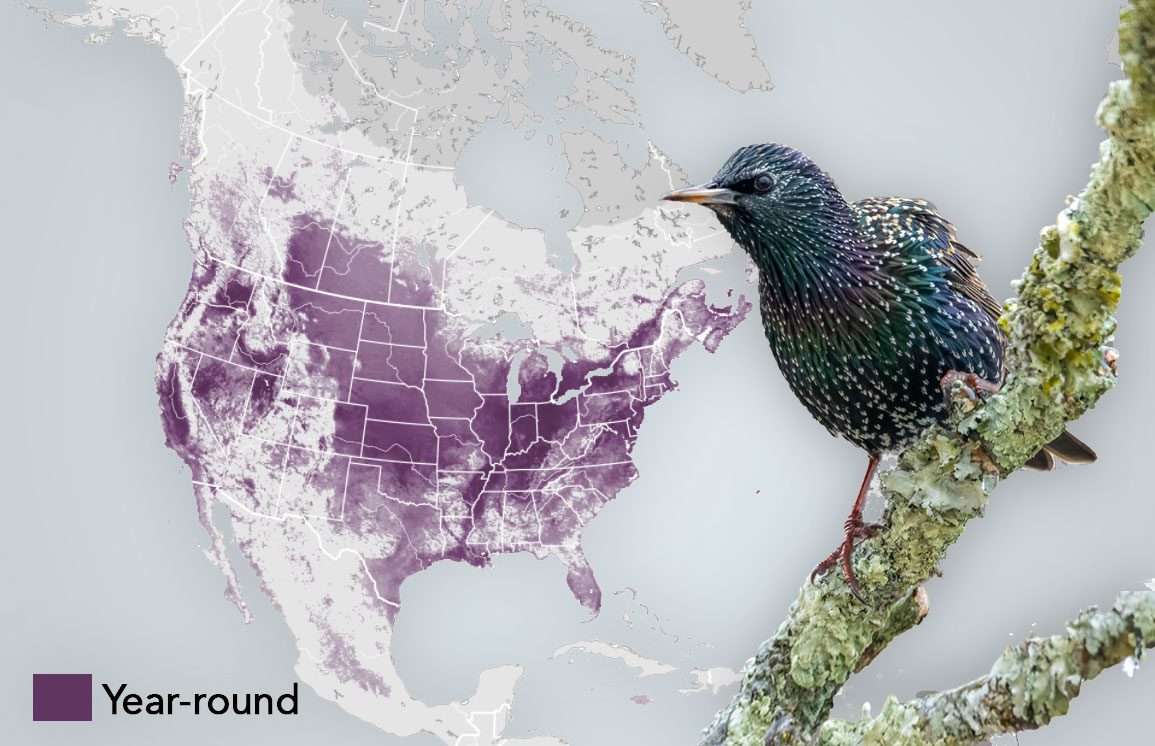

Love them or hate them, there’s no doubt the European Starling is a wildly successful bird. They can be found on six of the world’s seven continents (all except Antarctica) in all types of environments. A newly published study examines the genomes of North American starling populations to learn how they became so successful here.

“What I think is really cool is that the starlings in North America appear to have adapted to different conditions across the range,” says the study’s lead author, Natalie Hofmeister, a PhD candidate at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “So, it wasn’t just that they reproduced really quickly, and then just kept reproducing. It’s that they specialized once they arrived in new areas.”

The genetic differences among North American starlings are subtle. Researchers sequenced the genomes of starling populations from around the United States and found they were all remarkably alike. But the researchers did find the genetic signatures of change in areas of the genome that control how starlings adapt to variations in temperature and rainfall. For example, genomes of starlings in Arizona showed the strongest evidence of adaptation to hot and dry conditions, while starling genomes in the Pacific Northwest showed evidence of adjustment to cool, wet conditions.

Study authors concluded the birds had undergone “rapid local adaptation” to conditions not found in their native European range. And they did it quickly.

“The amazing thing about the evolutionary changes among starling populations since they were introduced in North America is that the genetic changes happened in a span of just 130 years,” says Hofmeister. “For a long time we didn’t think that was possible—that it took millions of years for changes to take hold at the genetic level.”

In 1890, Eugene Schieffelin, a pharmacist, released 80 European Starlings into Central Park in New York City, the first known introduction of starlings into North America. Those birds survived the winter, and another 60 joined them in 1891—just one of many introductions around the country meant to establish populations of all the birds mentioned in Shakespeare’s plays. Before long starlings made it to the Midwest, and by the 1940s they had been seen in nearly every state of the U.S. and province of Canada. The total continental population reached an estimated high of 200 million starlings in the 20th century.

Dustin R. Rubenstein, an associate professor in evolution and environmental biology at Columbia University who was not involved in the new starling genetic study, says that the research breaks new ground in the story of starling expansion in North America.

“This new study by Hofmeister and colleagues is an important first step in understanding why this species has been so successful in colonizing not only this continent, but also much of the world,” Rubenstein says.

Hofmeister’s ongoing research explores how European Starlings adapt so quickly to different conditions, while other species cannot. In another forthcoming study, she compares starling invasions in North America and Australia. Findings suggest that starlings may have wiring in their genomes to facilitate invasions, which allows them to proliferate in many different kinds of environments.

Despite their initial success, the European Starling population in North America has declined by more than 50% since 1970. The species is also declining in its native Europe.

More in This Issue

Some might say that fewer starlings is a good thing, as they’re a non-native species that can compete with native birds for prime cavity-nesting opportunities. Others revile starlings for their gregarious nature, as large starling flocks inflict millions of dollars in crop damage every year. But Hofmeister says they’re fascinating birds and really quite beautiful. And, they’re a great subject for scientists to study the genomic drivers of adaptation in avian evolution.

“Invasive species like these starlings can tell us something bigger about how nature works,” says Irby Lovette, Hofmeister’s advisor at the Cornell Lab and a coauthor of the study. “The same process of adaptation to local conditions that we can see happening in these starlings underlies the regional diversity within so many other bird species. At some deeper level, this is exactly how biodiversity originates.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library