The People Behind the Birds Named for People: Robert Stockton Williamson

By Alison Haigh, Editorial Assistant, Cornell Lab Science Communication Fund

September 18, 2017

From the Autumn 2017 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Most male and female woodpeckers wear similar, if not matching, plumage, but Williamson’s Sapsuckers did not get the memo. The female is subtly checked with brown and black, while the male is a stunning black with white stripes on the face and a deep red throat. Both sexes have vivid, highlighter-yellow bellies, but this is the only marking they have in common. The differences are so stark that for years, the nineteenth century’s best ornithologists were fooled into thinking the sexes were different species. Yet the bird’s namesake, Robert Stockton Williamson, probably never lost a wink of sleep over the matter.

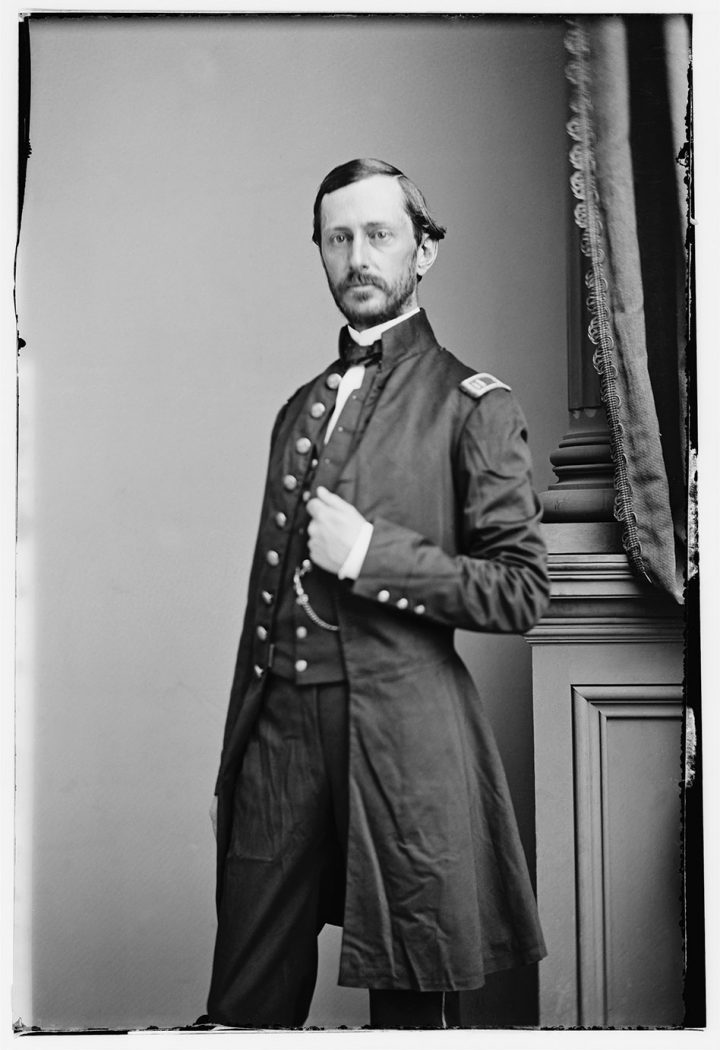

Williamson was an ambitious, no-nonsense engineer rather than a naturalist. After graduating from West Point fifth in his class, Williamson joined the Army as a topographical engineer and spearheaded expeditions into the Pacific wilderness to plan America’s first transcontinental railroad.

Williamson’s party was surveying in 1855, near Klamath Lake, Oregon, when the expedition’s naturalist, John Newberry, spied a striking black, white, and yellow woodpecker that was like nothing he’d seen before. As was customary for the time, he shot the specimen, described it as a new species, and named it for his boss: Picus williamsonii, Williamson’s Sapsucker.

In 1870, Spencer Fullerton Baird (of Baird’s Sparrow and Baird’s Sandpiper) called Newberry’s specimen “so entirely different from any other American bird as to require no special comparison.” It turns out special comparison is exactly what this bird required: the species had already been described just four years earlier—from that uniquely feathered female. For nearly 20 years, the two sexes remained “different” species, at least officially. Williamson might have been entirely unaware of the entire taxonomical development. After returning from the Oregon survey, he fought in the Civil War, serving with Colonel Burnside (whose name also became famous––not for a bird species, but for a beard style). Postbellum, he wrote a book on using barometers to map elevations, and returned to the Pacific Coast to build lighthouses, namely, Oregon’s oldest standing lighthouse on Cape Blanco. He also blew up a navigational hazard in San Francisco Bay.

It was around the time Williamson’s book on barometers came out that taxonomists were realizing their mistake with the sapsucker. In 1873 a naturalist in Colorado discovered a male and female nesting together and finally put the issue to rest. The species was renamed Sphyrapicus thyroideus, in deference to the original description of the female, but kept Williamson as the bird’s common name.

Williamson succumbed to tuberculosis in 1882 and was buried in San Francisco. After his many years improving navigation in the West, his name is perhaps best known for this baffling bird of mountain forests, to which he never gave a second thought.

Alison Haigh is an Environmental Biology and Applied Ecology major at Cornell University (Class of 2019). Her work on this story was made possible by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Science Communication Fund, with support from Jay Branegan (Cornell ’72) and Stefania Pittaluga.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library