Sound Sleuthing: Discovering New Bird Species by Listening for Them

Biologists are increasingly turning to the study of bird vocalizations to discover new species. The work requires curating hundreds of recordings, and it all starts with having a sensitive and curious ear.

By Kathi Borgmann

December 4, 2020

From the Winter 2021 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

In the summer of 1977, a group of fervent graduate students from Louisiana State University found themselves bouncing off the walls in Cusco, Peru, while they waited for transportation to the remote corners of the Madre de Dios region in the Amazon Basin for a field research expedition.

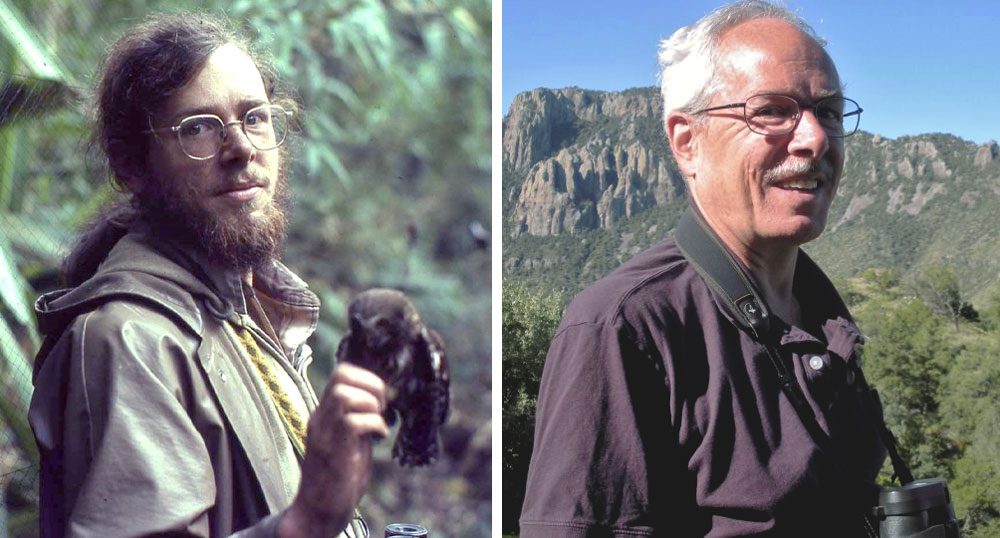

To stop from driving each other crazy during the downtime, the gang headed farther up into the Andes to do a little birding. It was then that a 23-year-old Tom Schulenberg spotted his first tapaculo—a little grayish-brown wrenlike bird—at the edge of a cloud forest.

Today Schulenberg is a gray-mustached veteran taxonomist and one of the editors for the Birds of the World online encyclopedia at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. But more than 40 years ago, Schulenberg was a scruffy graduate student at LSU who more than anything else just wanted to see more birds. And that one particular little brown bird at the edge of the cloud forest would puzzle him for years. Sure, it was a tapaculo, but which one?

Unbeknownst to him, he was just beginning a lifetime journey of studying tapaculos. A year later, Schulenberg and another group of LSU graduate students ascended the Cordillera de Colán in the state of Amazonas in northern Peru on another expedition. Their goal—to document all the bird species across the different elevations of the mountain range.

They spent five months climbing up and down mud-soaked paths, often days from the nearest road. Out before dawn, often with just a packet of crackers in their pockets, they routinely went from the sweat-soaked lower elevations to bone-chilling highlands, and everywhere in between.

“You had to be prepared for everything,” Schulenberg says.

With every boot-sucking step up the mucky ridge, the team heard tapaculos singing. But at various points along the way, the songs sounded different. When the team finally got a look at these seriously skulking birds, they realized that the tapaculos at various spots looked different, too.

“I was kind of excited about that,” says Schulenberg. But the consensus in the literature was that the differences in song, and the presence or absence of the white spot on the head, was just individual variation within a single tapaculo species.

“There were a lot of other things to get excited about on that trip,” says Schulenberg. A series of scientific species names rolled off his tongue as he mentioned all the other birds that the team rediscovered during the trip. But yet again, Schulenberg left Peru unsatisfied, bugged by a nagging question: What about those tapaculos that sounded so different?

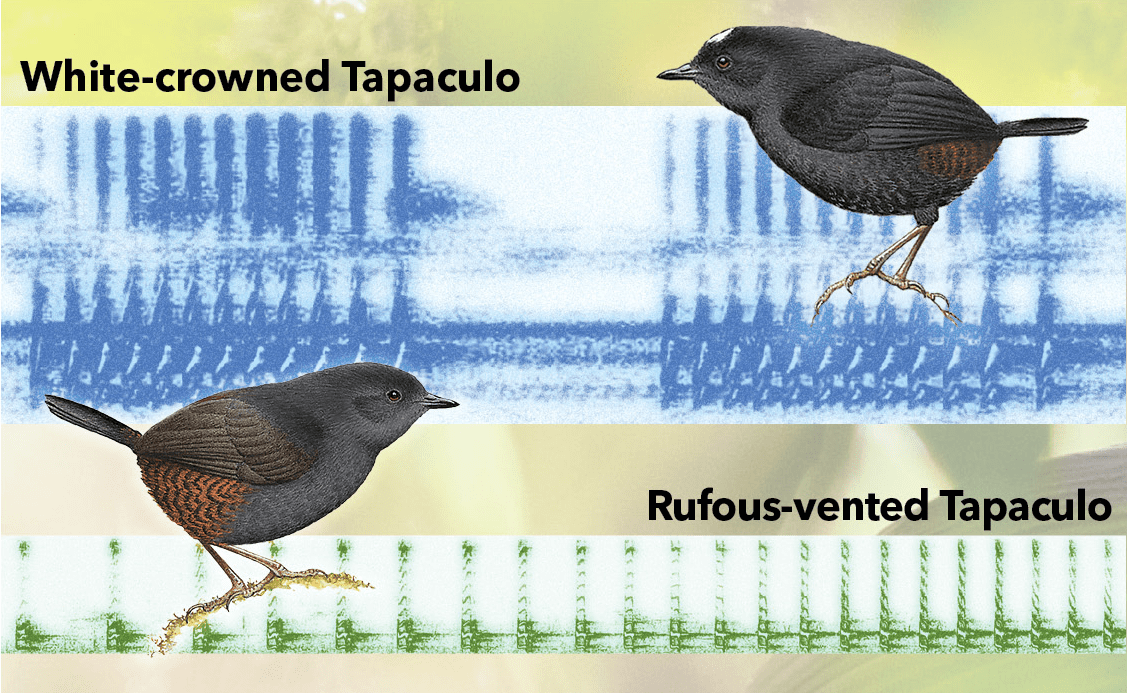

To solve that mystery, a team of Peruvian, Colombian, Danish, and American ornithologists came together in the late 1990s to mount a series of expeditions with the aim to get sound recordings from as many tapaculos, and from as many locations throughout South America, as possible. This small but devoted crew of ornithologists (including Schulenberg, who calls their crew the “scytalopologists”) have spent their careers studying the genus Scytalopus, to which most tapaculos belong. But much of their work has not involved adventuring through the cloud forests and paramo grasslands of the Andes. Rather, they have mostly been working in museums, sorting and sampling specimens, and in sound archives, sifting through hundreds of hours of vocalizations. Altogether, the team’s intercontinental effort has revealed the existence of more than 14 new species of tapaculos, all discovered in the last 25 years. And at last, one of Schulenberg’s nagging tapaculo questions was answered: It turns out that those were different tapaculos he had heard on his second expedition into the mountains in Peru in 1978, the White-crowned Tapaculo (which had that white spot on its head) and the Rufous-vented Tapaculo.

Describing new species isn’t always like an Indiana Jones movie, swashbuckling through remote corners of the world. It’s more like Sherlock Holmes, “a puzzle that is put together slowly and painstakingly over time,” says Pamela Rasmussen, assistant curator at the Michigan State University Museum. Rasmussen has worked on the descriptions of 11 new species, and she says not one of those discoveries involved a Eureka! moment of seeing a strange bird in the wild for the first time and right away recognizing it as a new species.

“It’s always been kind of the reverse and gradually coming to the realization that it’s a different species,” says Rasmussen.

Vocalizations are often the first head-scratching moment that lead many ornithologists to dig deeper.

“If we hadn’t known that the tapaculo species had different voices, we would have sampled fewer individuals because we would not have had a reason to suspect there was that much variation there,” says Schulenberg. Vocal differences are often the key that unlocks the first door in the journey of species discoveries.

In the last few years, more and more people have started recording bird sounds, bringing hundreds of thousands of recordings into the Cornell Lab’s Macaulay Library. Scientists are now listening in to discover new species and subspecies, and they’re learning more about the range of bird vocalizations not just among tapaculos, but among antpittas, Marsh Wrens, and even Chipping Sparrows.

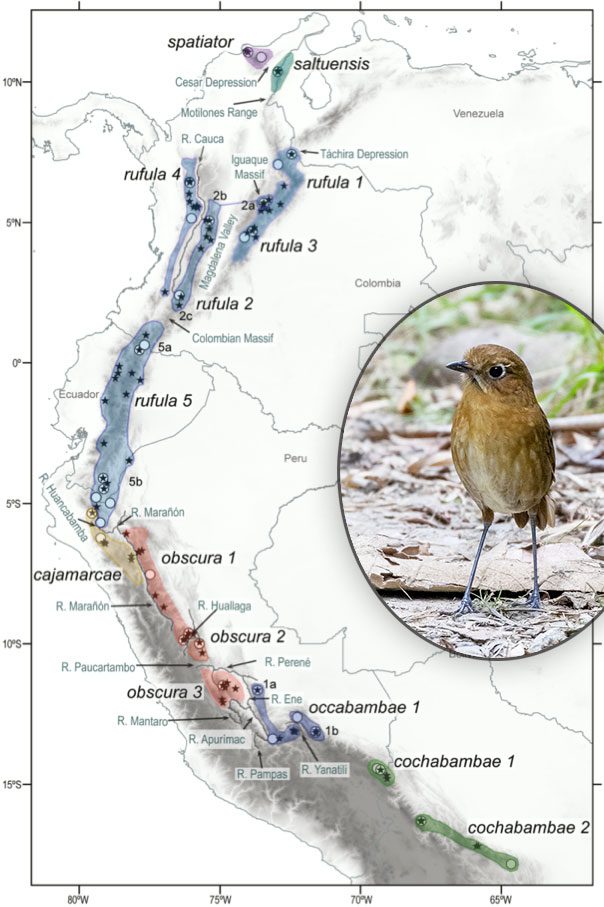

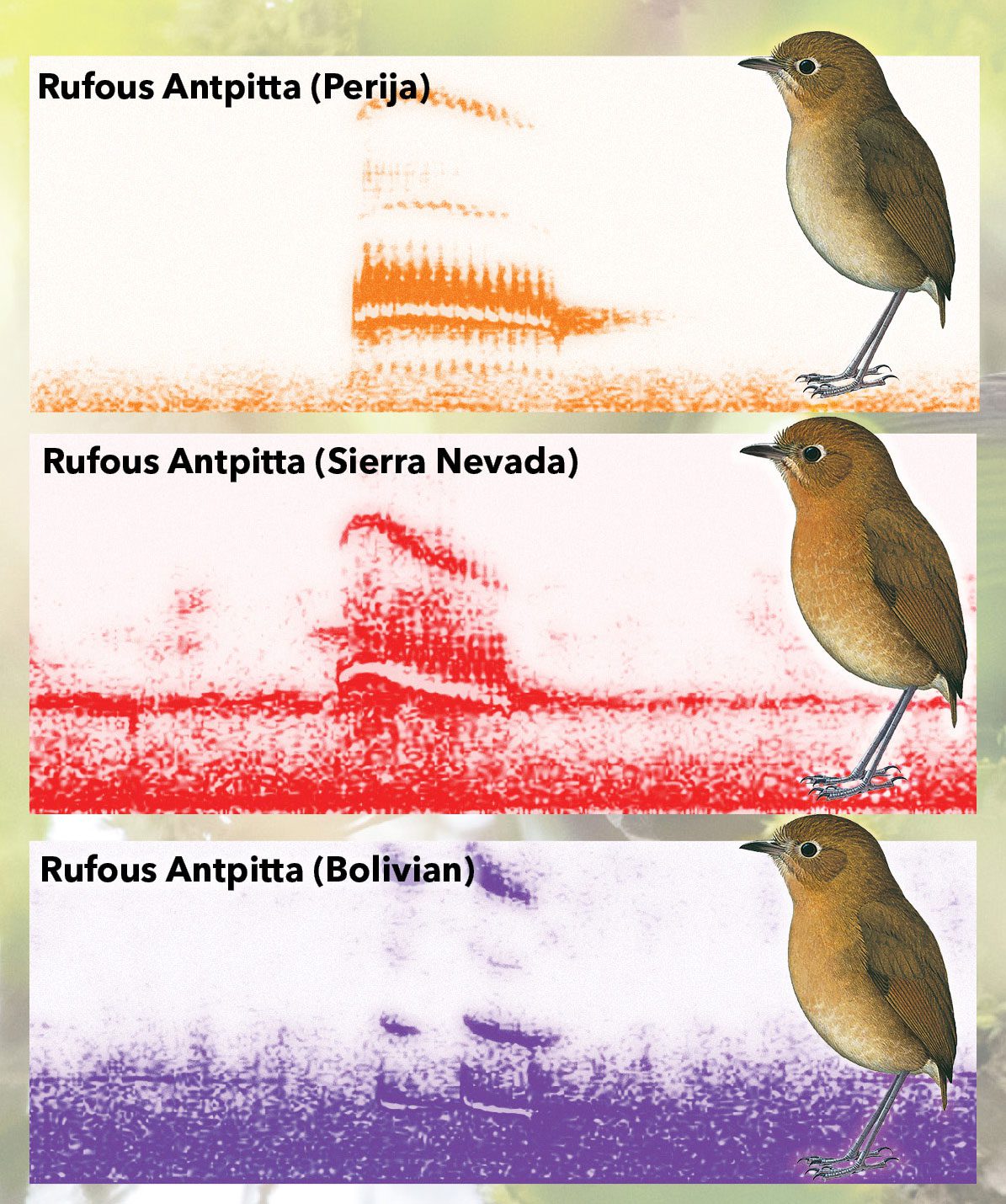

The Rufous Antpitta—a rusty-colored, egg-shaped ball of feathers perched atop a pair of long legs—is another species that is more than meets the eye. Rufous Antpittas occur all along several different mountain ranges in the Andes, from the Santa Marta Mountains in Colombia to the mountains of Cochabamba in Bolivia. From north to south these practically tailless, rusty-colored birds look very similar, only really varying in the shade of rust. But a collaborative group of Colombian, American, and Danish ornithologists noticed that the Rufous Antpittas sound different in each mountain range from Colombia to Bolivia. In the Perija Mountains in northern Colombia, the Rufous Antpitta’s short song is a fast trill, while in Colombia’s Santa Marta Mountains, the next mountain range to the west, the antpitta’s short song is higher-pitched and even faster. And in Bolivia, the corresponding song is a thin-sounding double note with no trill.

Species that look superficially similar but sound different are what ornithologists call cryptic species, and many cryptic species are new discoveries hiding in plain sight—waiting for someone to take note of genetic or vocal differences.

Mort Isler retired as an architect and urban planner in 1980 and became an ornithologist at age 51. He spent decades sussing out the various species among the lowland antbirds and antpittas in South America. But much of that time, Isler admits, he wasn’t down in the jungle or high atop Andean peaks. Instead, he was at a computer poring over vocalizations with the Cornell Lab’s Raven sound-analysis software.

Mort Isler and his collaborator (and wife) Phyllis Isler, who are affiliated with the Smithsonian Institution, still embarked on regular expeditions to South America to gather hundreds of audio recordings. But, he says, each trip would yield more questions than answers.

“When we came back from the field, we would be processing data for a much longer time than we actually collected data,” says Isler. Then he listened to additional audio samples at sound archives like the Macaulay Library or xeno-canto, because he wasn’t always able to get enough recordings throughout the entire range of the Rufous Antpitta.

“I’ve used sounds in the Macaulay Library for 40 years, and for that I’m very indebted to the library,” says Isler.

After years of research and analysis, Isler and his colleagues determined that the Rufous Antpitta is not one species, but 16—all of them common birds that are frequently encountered by locals, hiding in plain sight. Isler’s audio analysis showed distinct vocal differences that suggested separate species, which were confirmed by genetic analyses conducted by a team including research scientist Terry Chesser of the U.S. Geological Survey and Colombian professors Andrés Cuervo of the Institute of Natural Sciences and Daniel Cadena of the University of the Andes.

It’s no surprise that songs and calls are key to the identity of a bird species; after all, bird song is how the birds themselves figure out who’s who among the various species in their area. A bird’s vocalizations are a vital tool to defend territories, attract mates, and keep close social relationships with their mates and young.

More About Sound Recordings

“Song is where the rubber hits the road” for bird species identification, says Mike Webster, director of the Macaulay Library. For 17 years Webster has intensively studied Red-backed Fairywrens in Australia, which look mostly the same across their range, with just slight variation in plumage. But the bird’s song, Webster has found, forms a strong reproductive barrier.

Male fairywrens defend their territories with song, sort of like putting up a “keep out” sign in your yard, says Webster. But if the male sings a different regional dialect than its neighbor, that “keep out” sign has little meaning because it’s as if the sign were written in a different language. Males that don’t sing the local dialect are less likely to establish a territory and secure a mate. Hence, song variation can create a reproductive barrier, allowing populations that sing different songs to become more and more genetically different from each other. Given enough time and isolation, Webster says, song barriers like those in Red-backed Fairywrens could lead to reproductive isolation, and possibly speciation—the evolutionary divergence of new species from a single ancestor.

Cryptic species aren’t only lurking in the tropics. In fact, there could be new species lurking in many backyards in North America, just waiting for a more comprehensive look by scientists.

Take Marsh Wrens, for example. Across their breeding range from the East Coast to the West Coast, Marsh Wrens all look mostly alike, ranging from reddish-brown to grayish plumage. But the Marsh Wrens in the East sing liquid-sounding songs, while the wrens to the west have a harsh and grating song. The same song differences exist among Warbling Vireos, with western populations singing a choppier, less musical song than the Warbling Vireos found in the East.

Of both the Marsh Wren and the Warbling Vireo, Schulenberg says: “There are also marked vocal differences, with fairly abrupt transitions from one song type to the other. Voices are very clearly pointing to two different species in each case, and I hope I live long enough to see them formally recognized as such.”

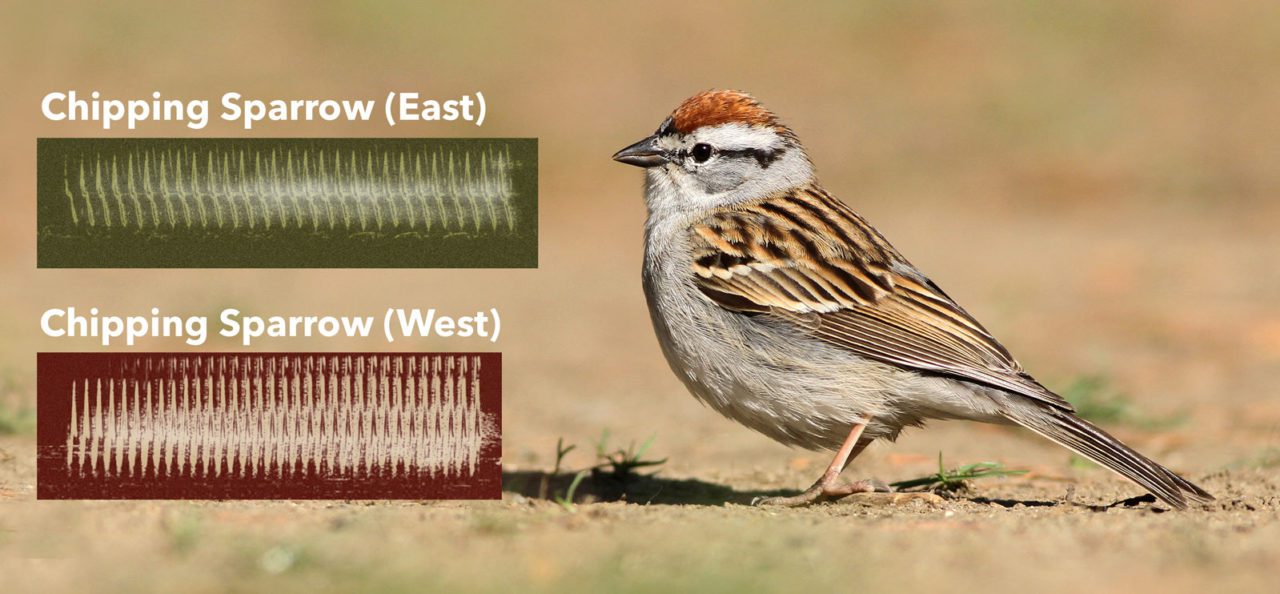

Chipping Sparrows, too, have vocal differences across the United States. Recent analyses by researchers at Vanderbilt University tapped into sound recordings submitted by community scientists to the Macaulay Library to confirm that eastern and western Chipping Sparrows sing different songs. Chipping Sparrows from the eastern U.S. and Canada sing a slower song with fewer notes than Chipping Sparrows in the West.

“The wide geographic coverage of citizen-science data provides an excellent opportunity to determine if changes in song have accumulated over time for an entire species,” says Vanderbilt biologist Abigail Searfoss, the lead researcher on the project. “[It allows] us to look for corresponding genetic differences in any subpopulations that differed in song.”

Upon DNA analysis, Searfoss didn’t find corresponding genetic differences between eastern and western Chipping Sparrows. But she says, “We should keep an eye on these song differences. As sound collections continue to grow over the years, it will be worthwhile to revisit this research to see if the populations’ songs diverge even further with time.”

Song Sparrows also sing a variety of songs from the East to the West, and they even look different across their range, which has led researchers to identify dozens of different Song Sparrow subspecies. But as with the Chipping Sparrows, researchers have not found genetic differences associated with plumage or vocal differences in Song Sparrows.

Determining if the variation in song really does signify a separate species is trickier for species like sparrows, wrens, and warblers, because they learn their songs. Regional variation in song among these birds could be due to learning instead of genetic differences. Species like tapaculos and antpittas, on the other hand, inherit their songs, so vocal differences are more likely to indicate genetic differences and result in separate species status.

Sound has played a part in the discovery of many bird species. Just how many is unclear, but from 2018 to 2020, at least 30 birds were elevated to species status in North and South America, in part because of analysis of audio recordings in the Macaulay Library.

Now that birders around the world can submit a sound recording with their eBird checklist, the number of audio files in the Macaulay Library is climbing rapidly. More than 26,000 recordings are pouring into the Macaulay Library each month from all over the world, creating what Webster calls “a treasure trove for researchers. They can dig in and easily look for geographic variation in vocalizations and maybe find a new species.”

In the past, Webster says, “it would have taken a researcher years, or maybe even their whole career, to collect enough recordings to understand if differences even existed in songs or calls.” Now more than 800,000 songs and calls are available to researchers everywhere to answer numerous questions. And technological advances are opening up even more possibilities.

Machine learning, Webster says, is going to “revolutionize the ability of people to find distinctive patterns in bird vocalizations. Artificial intelligence algorithms can quickly pull out vocal differences between two different populations, including differences that the human ear might not detect in an unbiased way.”

Just how many species are waiting to be discovered? Of the five scientists I interviewed for this article, none was willing to venture a guess, instead responding with a long pause and several ums.

“I can’t say,” said Rasmussen.

“I don’t know,” said Webster. “A lot.”

In his recently published book Birds New to Science: 50 Years of Avian Discoveries, David Brewer—an ornithologist with the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto—perhaps put it best:

“Only a reckless and courageous person would come up with an estimate.”

Kathi Borgmann is a communication coordinator for the Macaulay Library and eBird at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. She’s also a bird audio recordist, and her recordings in South America were used by scientists in the sound analysis that determined species status for the Perija Antpitta. Borgmann’s last feature for Living Bird magazine (The Forgotten Female, Summer 2019) earned honorable mention from the National Association of Science Writers 2020 Excellence in Institutional Writing Awards.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library