Site Fidelity: The Avian Treasures of Merritt Island, Florida

By Don Stap; Photographs by Cliff Beittel and Jerry Ting

July 15, 2012

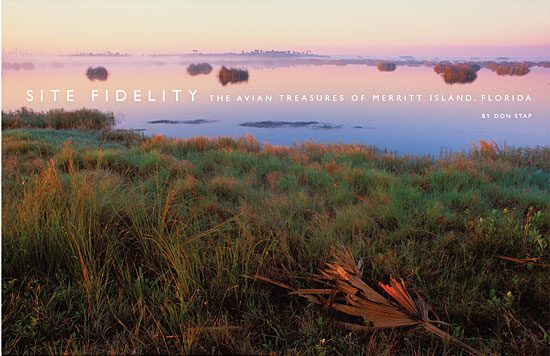

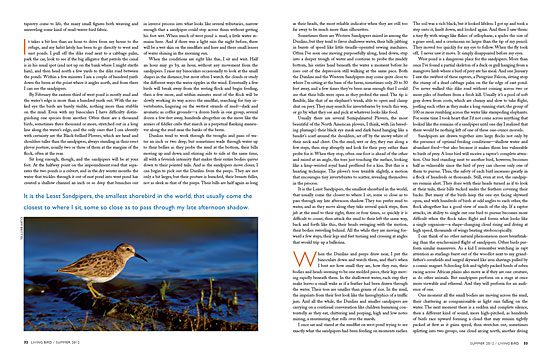

On a November day, on the cusp of another subtropical Florida winter, I am sitting on the edge of a dike road at Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge. Before me is an expanse of water that looks as deep as a mirror. It is evaporating along the edges, leaving the wet mud favored by Least Sandpipers and Semipalmated Plovers. The shallows nearest me are stippled with Western Sandpipers, and near them are several dozen Dunlins and Short-billed Dowitchers. Just beyond the dowitchers, in a deeper channel of water, a lone yellowlegs runs to and fro, and in the middle of the shallows on a narrow island of mud 100 yards out are a couple of hundred gulls and terns huddled as close together as their dispositions allow. I come here often at this time of year to watch the Dunlins hunch over their reflections in the water, to listen to the wind in the rushes and reeds, and to find again the stillness at the center of a flock of sandpipers flying low over the water.

Beyond the far edge of the water is the dull green of low-lying salt grass, which quickly gives way to a broad river of waist-high black needlerush, named for its fine point and the color it assumes this time of year as it dies back. To the north of where I sit the needlerush is replaced by Spartina, but this is not the raggedSpartina of most southeastern coastal marshes, Spartina alterniflora, but a more elegant species, Spartina bakeri, which grows in “high marshes” in clumps that look both in color and shape like shaving brushes stood on end. At the horizon is a band of dark green—a line of cabbage palms and slash pines growing on the berm on the other side of this impoundment.

From above, a perspective I enjoyed once in a helicopter that swept dreamlike over the land as two biologists counted wading birds, the area resembles a thick, brocaded rug laid 10 miles east to west and 25 miles north to south. The greens of palm trees, pines, wax myrtles, and mangroves seem woven in cloud shapes over a fabric of ochre and umber grasses, reeds, and rushes—or they encircle great cerulean blooms of shallow water. Standing on the ground, at any point in the marsh, the land and water are flat and wide open. Look up, and the cloud-brushed sky is pale blue and amazingly still.

Merritt Island, a barrier island halfway down Florida’s Atlantic coast, is attached by a thin strip of beach to Cape Canaveral, a spur of land made famous by the Kennedy Space Center. A sandbar that has been above sea level continuously for only 20,000 years, the Cape as well as the beach, Merritt Island, and the lagoons surrounding it—Indian River, Mosquito Lagoon, and Banana River—were sculpted by wind and waves as sea levels rose and fell during the 25 million years since Florida first emerged as land.

Native Americans arrived in the area 7,000 years ago, leaving behind shell middens and shards of pottery. The Spanish, who came in the early 1500s, planted orange trees they brought from China. In the 1700s British colonists drained and diked parts of the area for farming. But few people stayed for long. The orange trees died out, and native vegetation grew over what little remained of the settlements. Eventually, settlers were driven out by a particularly aggressive species of salt marsh mosquito, Aedes taeniorhynchus, estimated by the Department of Health to land on its victim at the rate of 500 individuals per minute. In the summer breeding seasons taeniorhynchus could produce a million offspring in one square yard of marsh. Thus, as the rest of the Florida coastline was developed Merritt Island remained largely unsettled, and the character of the place changed very little until the 1950s when NASA began buying up the land to build a space center.

The mosquitoes were a bane to the space center employees as well, so from 1959 to 1963, workers used a diesel-powered dragline that they threw out from a platform set in the marsh to scoop up sediment and dump it onto a pile. As they heaped up the sediment, edging forward through the marsh like an inchworm, they created a dike that would encircle an area, enabling them to hold water within it or release it through culverts when that served their purpose. In this way they could control water levels in the marshes and eliminate the mud where the mosquitoes laid their eggs. As they laid out dikes, they made them wide enough to also serve as access roads. When they were finished, they had divided 24,000 acres of the marsh into 76 impoundments.

Early on, NASA turned over 160,000 acres of the island to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to operate as a national wildlife refuge. The area contains an unusually varied mosaic of habitats: oak-palmetto scrub, pine flatwoods, hardwood hammocks, high marsh, and open estuarine lagoon waters.

More than 300 species of birds have been recorded at the refuge, 115 species of fish, 65 species of reptiles and amphibians, 25 species of mammals, and more than 1,000 vascular plants. Nineteen species of animals are listed as either endangered or threatened at the federal or state level, more than on any other national wildlife refuge in the contiguous 48 states. Dolphins cruise the lagoon waters. Otters slip in and out of drainage ditches. Gopher tortoises and indigo snakes favor the sandy soil associated with ancient dunes covered with palmetto. Armadillos nose their way along the grassy shoulders of the highways. Bobcats, foxes, and deer tend to remain out of sight, though more than once, at dusk, I’ve seen a bobcat walking down the center of a little-traveled dike road.

Unlike every other impounded marsh I’ve visited—where the impoundments are neat geometric shapes—the dike roads at Merritt Island follow the winding courses of old creeks and the natural shorelines of the lagoons. Because of the island’s size—220 square miles—and because most of those who visit the place stick to the one designated wildlife drive, I often encounter no one for hours at a time. If I walk an impoundment road closed to cars, I can count on having the place to myself. The local fishermen never venture more than 50 feet from the ice chests they keep in the back of their pickups.

I first began spending winter days at Merritt Island shortly after I moved to Florida 25 years ago to teach at the University of Central Florida. When I was offered the job, I remembered a week-long visit to Merritt Island two years earlier, my first encounter with birds that seemed exotic to a Midwest farm boy: Snowy Egrets, Wood Storks, Little Blue Herons, Glossy Ibises, Purple Gallinules, and, most remarkable of all, Roseate Spoonbills. As I weighed the decision to move from the Midwest to the subtropical Southeast, I recalled that when I closed my eyes each night during that visit, birds of all colors and shapes flew across blue skies into dreams that lasted until morning. This mitigated the feeling I had that in every other way the Florida landscape was all wrong for me.

During the first few winters at Merritt Island, I spent most of my time on the designated wildlife drive watching these showy birds that I could not seem to get enough of. And then I began to drive or walk the many little-used dike roads that were open to the public. At the time there were no available maps of these roads, no names for them, so I began making rough drawings of them in my notebooks. I measured distances, noted places where a berm was wide enough that I could pull the car off to the side and take a nap, and marked the location of cabbage palms that provided shade in the afternoon.

I wanted to know the names of the rushes, reeds, grasses, and bushes of the marsh. Eventually, I knew where to find an extensive stand of leather ferns, where Christmasberry grew, and where there were tangles of nicker bean with its spiny pods. And I knew a place where I could stand and see all three species of mangroves found in Florida—red, black, and white.

Most of all, though, I associated the dike roads with the birds I’d seen while traveling on them. On one long loop road I’d seen three Bonaparte’s Gulls dancing delicately—like terns—just above the water one January day, and moments later a Virginia Rail, and then a snipe, and, in the distance, Snow Geese. On another road I watched a Wood Stork do something inexplicable: eat a mangrove leaf. This big bird with an old man’s countenance and a long curved bill seemed to be testing a food that evolution had not prepared him for. The stork eyed the leaf, picked it up, dropped it, picked it up again, dropped it once more, then finally seized it with resolve. He tilted his head back and with much billclacking worked the tough leaf downward. Once he had it in his throat he shook his head vigorously from side to side, whether to get the leaf into his stomach or from a realization that he’d made a mistake I don’t know.

On the same road, not far from this spot but a few years later, I watched a Black-bellied Plover take several quick steps then jab his bill into the mud and extract a small crab, which he promptly took over to the water and swished around, hoping, I imagined, to rinse the mud off his meal but losing the crab in the process. I remembered this moment often over the years when I watched other Black-bellied Plovers stalking the mudflats, and I liked the thought of the plover, a bird with a dignified upright posture, fastidiously washing his meal; it didn’t occur to me till much later that perhaps it was the crab that had hold of the plover.

Even the bridge that crossed the Indian River onto Merritt Island had its pelicans and cormorants on the railings, and I learned to look closely at those cormorants that were riding low in the lagoon waters because more than once I saw one with a heavy bill and bulky body—and realized it was not a cormorant at all but a loon that had broken away from the big rafts of loons that winter in the waters off Canaveral National Seashore. In time the place came to inhabit me more than I did it. Miles away, no matter what dull space I happened to occupy, the dike roads came easily to mind, part memory, part longing. I could picture the turns they took, where the mangroves grew thick along their edges, and where they drew near the Indian River—lagoon on one side, marsh on the other, dolphins over my left shoulder, egrets and herons over my right.

Some days Merritt Island produced strange spectacles. One afternoon I raised my binoculars to watch vultures circling in a thermal overhead and saw above them several Wood Storks turning in a greater circle, and higher yet a group of white pelicans drifting in wide arcs. For several minutes I watched the three layers of this slow-motion aerial ballet. As I focused and refocused the binoculars in and out from one group to another, I lost myself in the sky, paying little attention to the sound of an approaching jet until I was jarred by the sight of it as it crossed—magnified 10 times—into my field of vision: a low-flying 747 with the space shuttle Atlantis strapped atop it, making its return to the Kennedy Space Center after a landing in California.

Despite the presence of the space center, I felt more at home at Merritt Island than I did in the shiny, busy environs of Orlando where I lived. Days at the wildlife refuge were also a respite from the intellectual activity of teaching, a kind of life I came to feel increasingly ill-suited for. And however compromised the wildlife refuge was by the space center operations, it was the least-compromised space in my life. I grew accustomed to the presence of the Vehicle Assembly Building, a great white monolith rising in the distance: 98,000 tons of steel occupying 8 acres. Yet it shrank in relation to the endless sky, and the sky was the domain of the shorebirds that wintered in great numbers at Merritt Island. Among the greatest long-distance migrants in the bird world, most species moved between nesting areas in the Arctic or subarctic and wintering sites as far south as Patagonia. Watching plovers and sandpipers on warm winter days beneath the ripples of cirrocumulus clouds three miles above me, I felt small and alone, and all the happier for it.

And it was the shorebirds that I’d become interested in. For reasons not entirely clear to me, I no longer went to Merritt Island to admire Wood Storks or Roseate Spoonbills or to search for the uncommon species that showed up in the area. Instead, I devoted my attention to shorebirds, especially the small sandpipers. It began one winter when I spent day after day, week after week, trying to distinguish Western Sandpipers from Semipalmated Sandpipers. I would sit in one spot and peer through my binoculars at flocks of birds that were no more than 50 feet away. I compared plumage and bill shapes, and listened to their peeping. In winter plumage, the two species are nearly identical, but still I watched and listened, and eventually I thought I could tell them apart. I was fairly certain I could hear the difference in their calls.

Then, I made a discovery. Although the refuge’s bird checklist indicated both species were present in the winter, in fact, virtually all Semipalmated Sandpipers winter south of the United States. There may have been a few mixed in with the Western Sandpipers I was seeing, but it was unlikely. A report published in 1975 made clear that semis do not winter in North America as had been widely reported for decades, and it found that all but one of the specimens of Semipalmated Sandpipers in Florida museums that had been collected in winter had been misidentified.

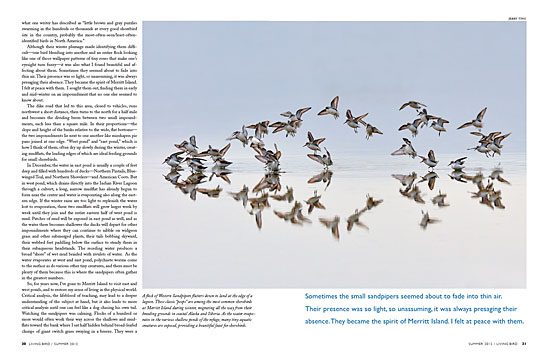

By this point, however, I’d become fascinated with all of the sandpipers. Unlike the colorful and elegant birds that drew my attention when I first arrived in Florida, the little sandpipers in winter were drab and inconspicuous. The smallest of them are known collectively as “peeps” from the sound they make, but the word was coined no doubt because of the difficulty of identifying what one writer has described as “little brown and gray puzzles swarming in the hundreds or thousands at every good shorebird site in the country, probably the most-often-seen/least-often-identified birds in North America.”

Although their winter plumage made identifying them difficult— one bird blending into another and an entire flock looking like one of those wallpaper patterns of tiny roses that make one’s eyesight turn fuzzy—it was also what I found beautiful and affecting about them. Sometimes they seemed about to fade into thin air. Their presence was so light, so unassuming, it was always presaging their absence. They became the spirit of Merritt Island. I felt at peace with them. I sought them out, finding them in early and mid-winter on an impoundment that no one else seemed to know about.

The dike road that led to this area, closed to vehicles, runs northwest a short distance, then turns to the north for a half mile and becomes the dividing berm between two small impoundments, each less than a square mile. In their proportions—the slope and height of the banks relative to the wide, flat bottoms— the two impoundments lie next to one another like misshapen pie pans joined at one edge. “West pond” and “east pond,” which is how I think of them, often dry up slowly during the winter, creating mudflats, the leading edges of which are ideal feeding grounds for small shorebirds.

In December, the water in east pond is usually a couple of feet deep and filled with hundreds of ducks—Northern Pintails, Blue-winged Teal, and Northern Shovelers—and American Coots. But in west pond, which drains directly into the Indian River Lagoon through a culvert, a long, narrow mudflat has already begun to form near the center and water is evaporating also along the eastern edge. If the winter rains are too light to replenish the water lost to evaporation, these two mudflats will grow larger week by week until they join and the entire eastern half of west pond is mud. Patches of mud will be exposed in east pond as well, and as the water there becomes shallower the ducks will depart for other impoundments where they can continue to nibble on widgeon grass and other submerged plants, their tails bobbing skyward, their webbed feet paddling below the surface to steady them in their subaqueous headstands. The receding water produces a broad “shore” of wet mud braided with rivulets of water. As the water evaporates at west and east pond, polychaete worms come to the surface as do various other tiny creatures, and there must be plenty of them because this is where the sandpipers often gather in the greatest numbers.

So, for years now, I’ve gone to Merritt Island to visit east and west ponds, and to restore my sense of living in the physical world. Critical analysis, the lifeblood of teaching, may lead to a deeper understanding of the subject at hand, but it also leads to more critical analysis until one can feel like a dog chasing his own tail. Watching the sandpipers was calming. Flocks of a hundred or more would often work their way across the shallows and mudflats toward the bank where I sat half hidden behind broad-leafed clumps of giant switch grass swaying in a breeze. They were a tapestry come to life, the many small figures both weaving and unraveling some kind of mud-water-bird fabric.

It takes a bit less than an hour to drive from my house to the refuge, and my habit lately has been to go directly to west and east ponds. I pull off the dike road next to a cabbage palm, park the car, look to see if the big alligator that patrols the canal is in his usual spot (and not up on the bank where I might startle him), and then head north a few yards to the dike road between the ponds. Within a few minutes I am a couple of hundred yards down the berm at the point where it angles north, and from there I can see the sandpipers.

By February the eastern third of west pond is mostly mud and the water’s edge is more than a hundred yards out. With the naked eye the birds are barely visible, nothing more than stubble on the mud. Even with my binoculars I have difficulty distinguishing one species from another. Often there are a thousand birds, sometimes three thousand or more, stretched out in a long line along the water’s edge, and the only ones that I can identify with certainty are the Black-bellied Plovers, which are head and shoulders taller than the sandpipers, always standing in their erect plover posture, usually two or three of them at the margins of the flock, often at the rear.

Sit long enough, though, and the sandpipers will be at your feet. At the halfway point on the impoundment road that separates the two ponds is a culvert, and in the dry winter months the water that trickles through it out of east pond into west pond has created a shallow channel an inch or so deep that branches out in inverse process into what looks like several tributaries, narrow enough that a sandpiper could step across them without getting his feet wet. When much of west pond is mud, a little water remains here. And if there was a light rain the night before, there will be a wet skin on the mudflats and here and there small lenses of water shining in the morning sun.

When the conditions are right like this, I sit and wait. Half an hour may go by, an hour, without any movement from the sandpipers. I raise my binoculars occasionally to look at the small shapes in the distance, but most often I watch the clouds or study the different ways the water ripples in the wind. Eventually a few birds will break away from the resting flock and begin feeding, then a few more, and within minutes most of the flock will be slowly working its way across the mudflat, searching for tiny invertebrates, lingering on the wettest strands of mud—dark and aromatic as coffee grounds—a dozen birds in one group, several dozen a few feet away, hundreds altogether on the move like the armies of fiddler crabs that march in a perpetual flanking maneuver along the mud near the banks of the berm.

Dunlins tend to work through the troughs and pans of water an inch or two deep, but sometimes wade through water up to their bellies as they probe the mud at the bottom, their bills moving up and down and stirring side to side at the same time, all with a feverish intensity that makes their entire bodies quiver down to their pointed tails. And as the sandpipers move closer, I can begin to pick out the Dunlins from the peeps. They are not only a bit larger, but their posture is hunched, their breasts fuller, not as sleek as that of the peeps. Their bills are half again as long as their heads, the most reliable indicator when they are still too far away to be much more than silhouettes.

Sometimes there are Western Sandpipers mixed in among the Dunlins, but they tend to favor shallower water, their bills jabbing in bursts of speed like little treadle-operated sewing machines. Often I’ve seen one moving purposefully along, head down, step into a deeper trough of water and continue to probe the muddy bottom, his entire head beneath the water a moment before he rises out of the depression still walking at the same pace. Both the Dunlins and the Western Sandpipers may come quite close to where I’m sitting at the base of the berm, sometimes only 20 to 30 feet away, and a few times they’ve been near enough that I could see that their bills were open as they probed the mud. The tip is flexible, like that of an elephant’s trunk, able to open and clamp shut on prey. They may search for invertebrates by touch this way, or go by what they see and pick at whatever looks like food.

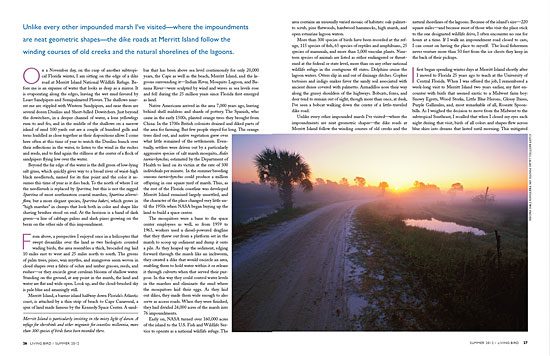

Usually there are several Semipalmated Plovers, the most beautiful of the North American plovers, I think, with (in breeding plumage) their black eye mask and dark band hanging like a bandit’s scarf around the shoulders, set off by the snowy white of their neck and chest. On the mud, wet or dry, they run along a few steps, then stop abruptly and look for their prey rather than probe for it. When they stop, often one foot is ahead of the other and raised at an angle, the toes just touching the surface, looking like a limp-wristed royal hand proffered for a kiss. But this is a hunting technique. The plover’s toes tremble slightly, a motion that encourages tiny invertebrates to scatter, revealing themselves in the process.

It is the Least Sandpipers, the smallest shorebird in the world, that usually come the closest to where I sit, some so close as to pass through my late afternoon shadow. They too prefer mud to water, and as they move along they take several quick steps, then jab at the mud to their right, three or four times, so quickly it is difficult to count, then attack the mud to their left the same way, back and forth like this, their heads swinging with the motion, their bodies swiveling behind. All the while they are moving forward a few steps, their legs and feet turning and crossing at angles that would trip up a ballerina.

When the Dunlins and peeps draw near, I put the binoculars down and watch them, and that’s when I best see how small they are, how they run, their bodies and heads seeming to be one molded piece, their legs moving rapidly beneath them. In the shallowest water, each step they make leaves a small wake as if a feather had been drawn through the water. Their toes are smaller than grains of rice. In the mud, the imprints from their feet look like the hieroglyphics of a traffic jam. And all the while, the Dunlins and smaller sandpipers are carrying on a continual conversation like children humming contentedly as they eat, chittering and peeping, high and low notes mixing, a murmuring that rolls over the marsh.

I once sat and stared at the mudflat on west pond trying to see exactly what the sandpipers had been feeding on moments earlier. The soil was a rich black, but it looked lifeless. I got up and took a step onto it, knelt down, and looked again. And then I saw them: a tiny fly with wings like flakes of cellophane, a spider the size of a grass seed, and a crustacean no larger than the tip of my pencil. They moved too quickly for my eye to follow. When the fly took off, I never saw it move. It simply disappeared before my eyes.

West pond is a dangerous place for the sandpipers. More than once I’ve found a partial skeleton of a duck or gull hanging from a mangrove limb where a bird of prey ate his meal. And one January I saw the swiftest of these raptors, a Peregrine Falcon, sitting atop the stump of a dead cabbage palm on the far edge of east pond. I’ve never walked this dike road without coming across two or more piles of feathers from a fresh kill. Usually it’s a pool of soft gray down from coots, which are clumsy and slow to take flight, jostling each other as they make a long running start, the group of 100 or more rumbling across the water like stampeding elephants. For some time I took heart that I’d not come across anything that looked like the remains of a sandpiper until one day I realized that there would be nothing left of one of these one-ounce morsels.

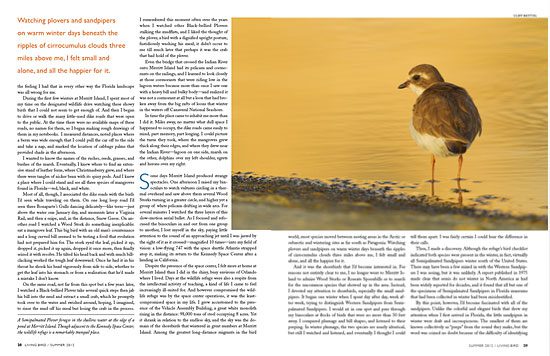

Sandpipers are drawn together into large flocks not only by the presence of optimal feeding conditions—shallow water and abundant food—but also because it makes them less vulnerable to birds of prey. A lone bird will receive a raptor’s complete attention. One bird standing next to another bird, however, becomes half as vulnerable since the bird of prey can choose only one of them to pursue. Thus, the safety of each bird increases greatly in a flock of hundreds or thousands. Still, even at rest, the sandpipers remain alert. They doze with their heads turned as if to look at their tails, their bills tucked under the feathers covering their backs. But many of the birds keep the one eye facing skyward open, and with hundreds of birds at odd angles to each other, the flock altogether has a good view of much of the sky. If a raptor attacks, its ability to single out one bird to pursue becomes more difficult when the flock takes flight and forms what looks like a single organism—a shape-changing cloud rising and diving at high speed, thousands of wings beating stroboscopically.

I can think of no other natural phenomenon more breathtaking than the synchronized flight of sandpipers. Other birds perform similar maneuvers. As a kid I remember watching in rapt attention as starlings burst out of the woodlot next to my grandfather’s cornfields and surged skyward like iron shavings pulled by a cosmic magnet. Schooling fish and tightly packed herds of zebra racing across African plains also move as if they are one creature, as do other animals. But sandpipers perform on a stage at once more viewable and ethereal. And they will perform for an audience of one.

One moment all the small bodies are moving across the mud, their chattering as companionable as light rain falling on the water. The next moment there is a sudden and complete silence, then a different kind of sound, more high-pitched, as hundreds of birds race upward forming a cloud that may remain tightly packed at first as it gains speed, then stretches out, sometimes splitting into two groups, one cloud arcing north, another diving and turning south. A few birds are sometimes lost in the division and distend into a string that slows for a few seconds before each bird gains speed again and rejoins a group. The flock twists and turns, the cloud swelling and contracting. Or it may ripple like a flag. Or undulate like ocean swells. Often the birds bank one way all at once, exposing their pale undersides, then turn back, showing their darker backs, and sometimes they flip several times so quickly they produce something like the shuttered flashes from a signal lamp—a semaphore sent out over the wind. These flights may occur frequently throughout a morning, or the birds may feed peacefully. Sometimes I see what has disturbed the flock, but more often than not it remains a mystery.

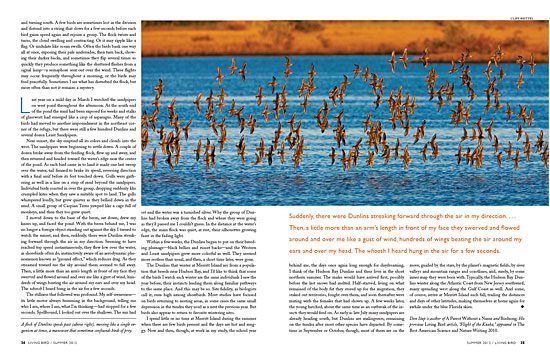

Last year on a mild day in March I watched the sandpipers on west pond throughout the afternoon. At the south end of the pond the mud had been exposed for weeks and stalks of glasswort had emerged like a crop of asparagus. Many of the birds had moved to another impoundment in the northeast corner of the refuge, but there were still a few hundred Dunlins and several dozen Least Sandpipers.

Near sunset, the sky emptied all its colors and clouds into the west. The sandpipers were beginning to settle down. A couple of dozen broke away from the feeding flock, flew up and away, and then returned and headed toward the water’s edge near the center of the pond. As each bird came in to land it made one last sweep over the water, tail fanned to brake its speed, reversing direction with a final serif before its feet touched down. Gulls were gathering as well in a line on a strip of mud beyond the sandpipers. Individual birds coasted in over the group, dropping suddenly like crumpled kites when they saw a suitable spot to land. The gulls whimpered loudly, but grew quieter as they bellied down in the mud. A small group of Caspian Terns yawped like a cage full of monkeys, and then they too grew quiet.

I moved down to the base of the berm, sat down, drew my knees up, and faced the pond. With the berm behind me, I was no longer a foreign object standing out against the sky. I turned to watch the sunset, and then, suddenly, there were Dunlins streaking forward through the air in my direction. Seeming to have reached top speed instantaneously, they flew low over the water, as shorebirds often do, instinctively aware of an aerodynamic phenomenon known as “ground effect,” which reduces drag. As they streamed toward me the sky around them seemed to fall away. Then, a little more than an arm’s length in front of my face they swerved and flowed around and over me like a gust of wind, hundreds of wings beating the air around my ears and over my head. The whoosh I heard hung in the air for a few seconds.

The stillness that followed was profound. My self-awareness— its little motor always humming in the background, telling me who I am, where I am, what I’m thinking—had stopped for a few seconds. Spellbound, I looked out over the shallows. The sun had set and the water was a tarnished silver. Why the group of Dunlins had broken away from the flock and where they were going as they’d passed me I couldn’t guess. In the distance at the water’s edge, the main flock was quiet, at rest, their silhouettes growing faint in the fading light.

Within a few weeks, the Dunlins began to put on their breeding plumage—black bellies and russet backs—and the Western and Least sandpipers grew more colorful as well. They seemed more restless than usual, and then, a short time later, were gone.

The Dunlins that winter at Merritt Island are from a population that breeds near Hudson Bay, and I’d like to think that some of the birds I watch each winter are the same individuals I saw the year before, their instincts leading them along familiar pathways to the same place. And this may be so. Site fidelity, as biologists call it, runs high among shorebirds. Most studies have focused on birds returning to nesting areas, in some cases the same small depression in the tundra they used as a nest the previous year. But birds also appear to return to favorite wintering sites.

I spend little or no time at Merritt Island during the summer when there are few birds present and the days are hot and muggy. Now and then, though, at work in my study, the school year behind me, the days once again long enough for daydreaming, I think of the Hudson Bay Dunlins and their lives in the short northern summer. The males would have arrived first, possibly before the last snows had melted. Half-starved, living on what remained of the body fat they stored up for the migration, they staked out territories, fought over them, and soon thereafter were mating with the females that had shown up. A few weeks later, the young hatched, about the same time as an outbreak of the insects they would feed on. As early as late July many sandpipers are already heading south, but Dunlins are malingerers, remaining on the tundra after most other species have departed. By sometime in September or October, though, most of them are on the move, guided by the stars, by the planet’s magnetic fields, by river valleys and mountain ranges and coastlines, and, surely, by some inner map they were born with. Typically, the Hudson Bay Dunlins winter along the Atlantic Coast from New Jersey southward, many spreading west along the Gulf Coast as well. And some, of course, arrive at Merritt Island each fall, trailing the distances and days of other latitudes, making themselves at home again for awhile under the blue Florida skies.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library