Seabirds off the Beaten Path in New Zealand’s Subantarctic Islands

Text and photographs by Cliff Beittel

April 15, 2012

Can you name a country that doesn’t have any native land mammals, where the dominant herbivore as recently as 800 years ago was a flightless, now-extinct 500-pound bird that could browse leaves 10 feet off the ground, and the national symbol is another genus of flightless, endangered bird?

Hint: it’s also the place where penguins first evolved and is currently home to six species of them, including two of the rarest.

Answer: New Zealand (or Aotearoa, in the Maori language).

Surprising? Not really. Both New Zealand and Antarctica were once part of Gondwana, the ancient supercontinent, and remained in close proximity when penguins first evolved some 65 million years ago. Today, having drifted north from the Ross Sea side of Antarctica, New Zealand seems far removed from Antarctica, whereas the Antarctic Peninsula, with its ecotourism boom, practically reaches up to touch South America. Still, the oldest penguin fossils yet found are from New Zealand, and six species breed there, including four endemics.

Most of New Zealand’s penguins and albatrosses nest on subantarctic islands south and east of its two main islands. Campbell Island, the southernmost of the country’s subantarctic islands, lies 420 miles south of South Island, the less populated of the two main islands. Campbell and the other subantarctic islands are remote, ecologically sensitive, uninhabited places. Permits allow just 600 visitors a year, less than 3 percent of the 21,000 who visit Antarctica each year. Zegrahm Expeditions had the hard-to-get permits, so I joined their cruise, led by noted seabird expert Peter Harrison, on the 335-foot Clipper Odyssey.

Marlborough Sounds

Our first morning on the ship, rain fell on the wilderness of fog, water, and foliage that is Marlborough Sounds—a sinuous maze of channels and forested ridges formed by the partial drowning of the top of South Island. It seemed a world away from the sunny urbanity of Wellington, the capital of New Zealand, but actually the city lies just across Cook Strait, which separates the North and South Islands by as little as 14 miles.

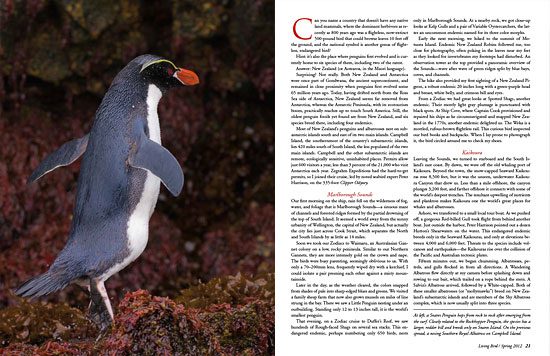

Soon we took our Zodiacs to Waimaru, an Australasian Gannet colony on a low, rocky peninsula. Similar to our Northern Gannets, they are more intensely gold on the crown and nape. The birds were busy parenting, seemingly oblivious to us. With only a 70–200mm lens, frequently wiped dry with a kerchief, I could isolate a pair preening each other against a misty mountainside. Later in the day, as the weather cleared, the colors snapped from shades of pale into sharp-edged blues and greens. We visited a family sheep farm that now also grows mussels on miles of line strung in the bay. There we saw a Little Penguin nesting under an outbuilding. Standing only 12 to 13 inches tall, it is the world’s smallest penguin.

That evening, on a Zodiac cruise to Duffer’s Reef, we saw hundreds of Rough-faced Shags on several sea stacks. This endangered endemic, perhaps numbering only 650 birds, nests only in Marlborough Sounds. At a nearby rock, we got close-up looks at Kelp Gulls and a pair of Variable Oystercatchers, the latter an uncommon endemic named for its three color morphs.

Early the next morning, we hiked to the summit of Motuora Island. Endemic New Zealand Robins followed me, too close for photography, often poking in the leaves near my feet as they looked for invertebrates my footsteps had disturbed. An observation tower at the top provided a panoramic overview of the Sounds—wave after wave of green ridges split by blue bays, coves, and channels.

The hike also provided my first sighting of a New Zealand Pigeon, a robust endemic 20 inches long with a green-purple head and breast, white belly, and crimson bill and eyes.

From a Zodiac we had great looks at Spotted Shags, another endemic. Their mostly light gray plumage is punctuated with black spots. At Ship Cove, where Captain Cook provisioned and repaired his ships as he circumnavigated and mapped New Zealand in the 1770s, another endemic delighted us. The Weka is a mottled, rufous-brown flightless rail. This curious bird inspected our bird books and backpacks. When I lay prone to photograph it, the bird circled around me to check my shoes.

Kaikoura

Leaving the Sounds, we turned to starboard and the South Island’s east coast. By dawn, we were off the old whaling port of Kaikoura. Beyond the town, the snow-capped Seaward Kaikouras rose 8,500 feet, but it was the unseen, underwater Kaikoura Canyon that drew us. Less than a mile offshore, the canyon plunges 3,200 feet, and farther offshore it connects with some of the world’s deepest trenches. The resultant upwelling of nutrients and plankton makes Kaikoura one the world’s great places for whales and albatrosses.

Ashore, we transferred to a small local tour boat. As we pushed off, a gorgeous Red-billed Gull took flight from behind another boat. Just outside the harbor, Peter Harrison pointed out a dozen Hutton’s Shearwaters on the water. This endangered endemic breeds only in the Seaward Kaikouras, and only at elevations between 4,000 and 6,000 feet. Threats to the species include volcanoes and earthquakes—the Kaikouras rise over the collision of the Pacific and Australian tectonic plates.

Fifteen minutes out, we began chumming. Albatrosses, petrels, and gulls flocked in from all directions. A Wandering Albatross flew directly at my camera before splashing down and rowing to our bait, which trailed on a rope behind the stern. A Salvin’s Albatross arrived, followed by a White-capped. Both of these smaller albatrosses (or “mollymawks”) breed on New Zealand’s subantarctic islands and are members of the Shy Albatross complex, which is now usually split into three species.

Next, another giant albatross arrived, a mature Northern Royal. Unlike the Wandering Albatross, its upper bill has a black cutting edge I could see even as the bird circled the boat; unlike a Southern Royal Albatross, the Northern has all-dark upper wings. A Southern Royal arrived minutes later. It had the same black cutting edge on its bill, but white leading edges on its upper wings.

Often kneeling in sloshing water by the transom with a 70–200mm zoom lens, I got good photographs of all these species, plus Cape and Westland petrels. Cape Petrels I had seen in Antarctica, but the Westland was new for me—an uncommon endemic with all-black plumage.

Christchurch, Dunedin, and Taiaroa

Christchurch has been a gateway to Antarctica since the days of explorers Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton. At the International Antarctic Centre, I was most taken by an aquarium where rehabbing Little Penguins can be viewed both above and below water. At Willowbank Wildlife Reserve, we dimly saw kiwi—one of New Zealand’s national symbols—in a dark kiwi house, and got good looks outside at other endemic and Australasian species.

Back on the Clipper Odyssey in Lyttelton, a suburb reached from Christchurch by tunnel, Red-billed Gulls circled the ship. Standing on an upper deck, I photographed gulls gliding over green water. The epicenter of the deadly February 2011 Christchurch earthquake lay five kilometers below where I stood. Lyttelton Harbour is the caldera of an ancient volcano.

A brilliant sunrise painted the South Pacific off Taiaroa Head, the headland at the end of Otago Peninsula, as we entered the 12-mile channel into Dunedin, founded by Scottish immigrants in the 1850s. From town we followed the narrow coast road to Taiaroa, which has a double distinction as the only mainland breeding albatross colony in the Southern Hemisphere and the only place where Northern and Southern Royal albatrosses interbreed. Most of the birds are Northern Royals; most Southern Royals breed on Campbell Island.

Back at Dunedin’s dock, a local pipe band in tartan kilts played us off. So far, we had hugged the coast, but now we were headed hundreds of miles out to Campbell Island and wouldn’t see land for two days. The bagpipes were alternately rousing and melancholy. I’d seen sendoffs like this in movies, most memorably Scott’s departure for Antarctica in the great 1985 film, The Last Place on Earth. I was moved by the music, the history, and the small chance of trouble at sea. I stayed at the rail, not wanting the ceremony to end as the water widened and the music faded.

Subantarctic Islands

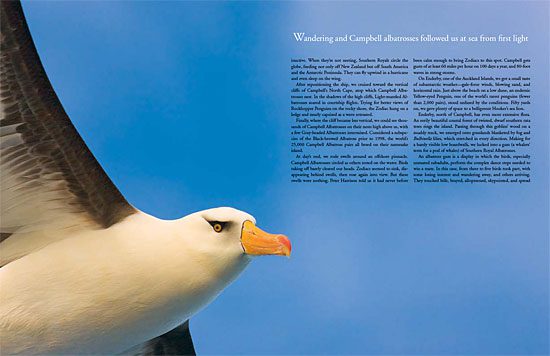

Wandering and Campbell albatrosses followed us at sea from first light, along with Northern Giant-Petrels and Cape Petrels. By late afternoon, Campbells were everywhere, often hanging directly over the stern. Their honey-colored eyes were obvious even at a distance, but at close range were hypnotic.

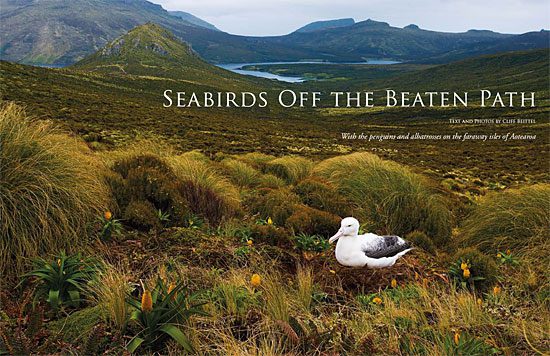

Next morning, we landed on the east side of Campbell Island and began climbing a narrow two-mile boardwalk, covered with chicken wire for traction (rain or drizzle falls 325 days a year, and light snow, too, though winter lows average only 37 degrees Fahrenheit). Some 99 percent of the world’s Southern Royal Albatrosses breed on Campbell, and the boardwalk was our stairway to their nesting grounds.

Much of Campbell Island is covered in grasses, including tussock. But forbs in New Zealand’s subantarctic region are more diverse and colorful than on subantarctic islands elsewhere. Especially remarkable are the megaherbs—species with huge leaves and large, colorful flowers, which for some reason haven’t undergone the normal stunting typical of wet, cold, and windy climates. As we climbed, the bright yellow flowers of the megaherb Bulbinella rossii were in bloom.

After an hour’s slog, we reached Royal Albatross nests near the top of the boardwalk. Some nests have spectacular views of the harbor and sea below. The birds mostly dozed. Incubating albatrosses sit for weeks, mostly in a state of broodiness or torpor to conserve energy. It’s strange to see these avian athletes so inactive. When they’re not nesting, Southern Royals circle the globe, feeding not only off New Zealand but off South America and the Antarctic Peninsula. They can fly upwind in a hurricane and even sleep on the wing.

After repositioning the ship, we cruised toward the vertical cliffs of Campbell’s North Cape, atop which Campbell Albatrosses nest. In the shadows of the high cliffs, Light-mantled Albatrosses soared in courtship flights. Trying for better views of Rockhopper Penguins on the rocky shore, the Zodiac hung on a ledge and nearly capsized as a wave retreated.

Finally, where the cliff became less vertical, we could see thousands of Campbell Albatrosses on their nests high above us, with a few Gray-headed Albatrosses intermixed. Considered a subspecies of the Black-browed Albatross prior to 1998, the world’s 25,000 Campbell Albatross pairs all breed on their namesake island.

At day’s end, we rode swells around an offshore pinnacle. Campbell Albatrosses circled as others rested on the water. Birds taking off barely cleared our heads. Zodiacs seemed to sink, disappearing behind swells, then rose again into view. But these swells were nothing. Peter Harrison told us it had never before been calm enough to bring Zodiacs to this spot. Campbell gets gusts of at least 60 miles per hour on 100 days a year, and 80-foot waves in strong storms.

On Enderby, one of the Auckland Islands, we got a small taste of subantarctic weather—gale-force winds, blowing sand, and horizontal rain. Just above the beach on a low dune, an endemic Yellow-eyed Penguin, one of the world’s rarest penguins (fewer than 2,000 pairs), stood unfazed by the conditions. Fifty yards on, we gave plenty of space to a belligerent Hooker’s sea lion.

Enderby, north of Campbell, has even more extensive flora. An eerily beautiful coastal forest of twisted, dwarf southern rata trees rings the island. Passing through this goblins’ wood on a muddy track, we emerged onto grasslands blanketed by fog and Bulbinella lilies, which stretched in every direction. Making for a barely visible low boardwalk, we lucked into a gam (a whalers’ term for a pod of whales) of Southern Royal Albatrosses.

An albatross gam is a display in which the birds, especially unmated subadults, perform the complex dance steps needed to win a mate. In this case, from three to five birds took part, with some losing interest and wandering away, and others arriving. They touched bills, brayed, allopreened, skypointed, and spread their wings. At one point, a new bird arrived by air, a white ghost in the fog, buzzing the gammers five or six times before landing and joining them.

Still closer to South Island, Snares Island, though rocky and steep, has forests of giant daisy trees. Here another forest-nesting penguin sometimes perches on low branches. The Snares Penguin breeds only at Snares. A relative of the Rockhopper, it looks and acts much the same, but it has a bigger, redder bill. Scores of penguins at a time pop from the thick bull kelp that surrounds the island and hop up the pitched granite slabs to their nests.

Only researchers are allowed to land at Snares, so we cruised the shoreline in Zodiacs. Going to and from the ship, we were surrounded by rafts of penguins, many bathing before coming ashore. At day’s end, tens of thousands of Sooty Shearwaters blanketed the water before retiring for the night.

Ulva, Songbirds, and Extinctions

Our final outlying island, Ulva, is too far north to be subantarctic. We walked in intermittent showers in a dripping green preserve of native trees and ferns. It differed from the mainland in the number and variety of songbirds. In addition to common birds we’d seen elsewhere, there were Saddlebacks (named for a rufous patch on their backs), a Rifleman (New Zealand’s smallest bird), and a spectacular pair of noisy Yellowheads close overhead. Yellowheads, which remind me of Prothonotary Warblers, normally stay high in the canopy.

Ulva is a reminder of New Zealand’s past. Here, as at Motuora and the subantarctic islands, rats and other introduced species have been eliminated. On the main islands, many native birds hang on only inside predator-free exclosures, fenced like maximum-security prisons to protect them from the more than 30 species of introduced mammals, including rats, weasels, possums, dogs, and cats. The first rats arrived with early Polynesian navigators about 1,500 years ago and produced an initial wave of extinctions among birds. Many were flightless ground dwellers that had evolved without mammalian predators.

Back in Wellington, before boarding ship, we had learned of a second wave of extinctions from a life-sized model of a Haast’s Eagle—the largest eagle that ever lived—attacking a Giant Moa. The display, at Wellington’s spectacular harbor-front Te Papa (Our Place) national museum, is based on skeletal remains. At least 10 species of moa once existed. Flightless relatives of ostriches, rheas, and emus, they were the dominant herbivores, and their only predator was the huge eagle. But after the Maori settled in New Zealand in around 1280, both the eagle and the moa were soon extinct.

Southern Alps

We traced Captain Cook’s route through Dusky and Doubtful Sounds in Fjordland National Park, on the South Island’s southwestern coast, where the luckiest among us saw a rare Fjordland Crested Penguin. Next morning, it rained hard in Milford Sound (one of the world’s wettest places, averaging 283 inches per year). Hundreds of waterfalls poured down the fjord’s 4,000- foot walls.

At Milford Landing, we boarded motor-coaches for the drive to Queenstown and home. It was a tortuous climb out of the sound, across raging torrents, up switchback after switchback, to Homer Tunnel, through which the narrow road climbs at a 10 percent grade as it pierces three-quarters of a mile of New Zealand’s Southern Alps. At the tunnel’s eastern portal, we pulled into a parking lot for a last rainy visit with wild New Zealand.

Everyone else went looking for endemic South Island Wrens, but I couldn’t tear myself from the parking lot. As cars queued up at the red light to enter the one-way tunnel, Kea, New Zealand’s endemic alpine parrot, landed on car hoods, rearview mirrors, and open windows to beg for handouts. Fed or not, many Kea flew to the roofs of cars and vans—out of sight of vehicle occupants—and attacked antennas and weatherstripping. Kea are playful, highly intelligent, and sometimes troublesome— 150,000 were killed between 1860 and 1970 because some were suspected of killing weakened sheep. Only 1,000 to 5,000 of the birds remained in 1986 when they were given protected status.

Kea are survivors of New Zealand’s third wave of extinction, which started with European settlement in about 1840. The new colonists introduced other exotic species such as sheep and house cats; their agriculture changed the landscape forever. The South Island’s spectacular mountains, to which Kea are endemic, remained largely intact. But the lowland forests and wetlands were converted to farming, their broad diversity replaced with a handful of crops.

New Zealand’s subantarctic islands and their nesting seabirds are protected. But threats to the mainland remain, notwithstanding its unspoiled appearance. The late Geoff Park, a New Zealand ecologist, wrote that his country was “the last occupiable landmass to be reached” but that “few countries’ native ecosystems have been so comprehensively ravaged…or have had such a high proportion of their native species rendered extinct, or nearly so, in such a brief space of time as has New Zealand’s.” Those lines are from Park’s 1997 essay, “Conservation: Extinction Wave or Healing Tide?” which found optimism only in individual and local action: “More than ever before, what we call ‘conservation’ might be happening less by government intervention than via simple citizenship…What the Californian philosopher of ecology Gary Snyder calls finding our place and digging in.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library