Scrubland Survivor: the Florida Scrub-Jay

By Hugh Powell October 15, 2008

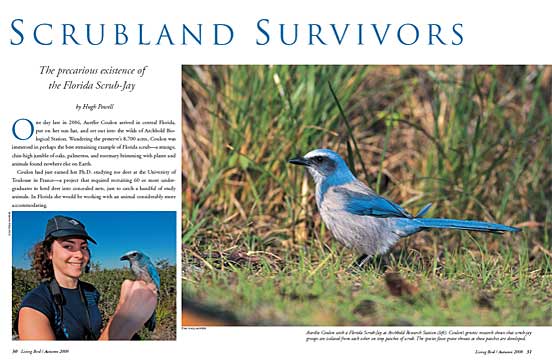

One day late in 2006, Aurélie Coulon arrived in central Florida, put on her sun hat, and set out into the wilds of Archbold Biological Station. Wandering the preserve’s 8,700 acres, Coulon was immersed in perhaps the best remaining example of Florida scrub—a strange, chin-high jumble of oaks, palmettos, and rosemary brimming with plants and animals found nowhere else on Earth.

Coulon had just earned her Ph.D. studying roe deer at the University of Toulouse in France—a project that required recruiting 60 or more undergraduates to herd deer into concealed nets, just to catch a handful of study animals. In Florida she would be working with an animal considerably more accommodating.

As she held up a peanut and made a low chuckling call, a blue-and-gray bird instantly swooped in from a nearby perch, landed on her outstretched hand, and took the nut.

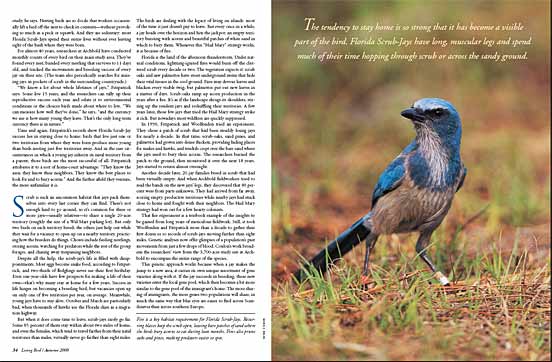

It was a Florida Scrub-Jay, the state’s only endemic bird species and an icon of the parched, sandy hills that fleck the Florida peninsula. The bird is a bundle of contradictions: a jay that’s afraid of flying; a suburban bird that can’t survive in the suburbs; an endangered species that will perch on your head. And though its jay and crow relatives are among the most adaptable of birds, this species seems incapable of surviving anywhere except in the scrub.

The scrub-jay is on the losing end of a struggle for Florida’s dwindling scrub habitat, which is in high demand for housing developments and citrus groves. The bird’s population has waned ever since development began to boom in the early 20th century. Now, about 5 percent of the state’s original scrub habitat remains, and jay numbers have fallen to less than 10 percent of what they once were. The bird on Coulon’s hand was one of fewer than 8,000 Florida Scrub-Jays remaining in the world.

After a few weeks at Archbold, Coulon spent the next two years at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, analyzing the genetic similarities among the birds in all 21 of the jay’s remaining strongholds across Florida. With colleagues including John Fitzpatrick, director of the Lab of Ornithology, and Irby Lovette, director of the Lab’s Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program, she uncovered an astounding result: Florida Scrub-Jays fall into 10 geographically separate groups. They mix so infrequently that, genetically, some groups are nearly as different as two related species, the Western Scrub-Jay and the Island Scrub-Jay, are from each other.

The results of the study, published in the journal Molecular Ecology in April 2008, are a high-tech affirmation of 40 years of intensive fieldwork that point to the same conclusion: Florida Scrub-Jays behave as if they live on islands, cramming themselves into small patches of scrub and rarely venturing out over foreign territory.

“They just won’t fly long distances through prairie, forest, or marsh,” says Fitzpatrick, a former director of Archbold Biological Station who has studied the jays since 1972. “You can see them hating it when they try. And their reluctance is part of this glue holding them, ecologically and socially, to the place where they were born.”

The tendency to stay home is so strong that it’s become a visible part of the bird. Florida Scrub-Jays have long, muscular legs and spend much of their time hopping through scrub or across the sandy ground. When they fly, it’s a hesitant affair of fluttering wings, pumping tail, and an almost grateful swoop to a nearby perch.

Scientists call it “limited dispersal ability.” Once a survival trait of the Florida Scrub-Jay, it is now one more element pushing the species toward extinction. As the genetics show, whole segments of the remaining scrub-jay population lie over the horizon, almost as if they don’t exist to each other. But by helping to understand the bird’s past, this new research offers directions and hope for future conservation efforts.

The evolutionary history of the Florida Scrub-Jay starts on a pre-ice-age sand dune, sweeps into the present in a brush fire, and ends up squeezed between an orange grove and a subdivision. Jays colonized Florida more than two million years ago, scientists believe. The Gulf of Mexico was lower then, allowing jays to arrive through arid landscapes from western North America, where the Western Scrub-Jay remains abundant to this day. As glaciers built up and subsequently receded, changing sea levels built sand dunes in parallel lines running down the spine of the peninsula.

Rainwater runs through this sand like water through a coffee filter, so despite Florida’s abundant rainfall, the scrub became a place ruled by drought. When sea levels rose, the dunes became subtropical desert islands marooned by salt water. Thus began the isolation of the scrub habitat—and of the Florida Scrub-Jay.

The resulting scrub community is a storehouse of evolutionary oddities, many of them in miniature. It supports some 40 endemic species of plants; dozens of insects, a skink, a lizard, and a mouse that occur nowhere else; a burrowing tortoise that provides homes for many of them; and a blue-black snake that reaches eight feet in length. Yet pristine scrub doesn’t take your breath away as do, say, the dim spaces of a redwood forest or the endless grassy plains and alligator wallows of the Everglades.

It can seem like a jumbled mess that is either just past its prime or not quite there yet. Spindly oaks wave in the breeze, looking like anemic saplings from a brand-new cul-de-sac, except that these trees are hundreds, or perhaps thousands, of years old. Saw palmettos point vivid green fans at the sky, a waist-high scuffle of Stegosaurus backs. Every so often, the plants give way entirely and a bare patch of fine white “sugar sand” takes over.

At Archbold, scrub-jays prize those patches, using the deep, loose sand to bury acorns for winter. Fitzpatrick’s research program here—started by the late Glen Woolfenden of the University of South Florida—is one of the most detailed, long-term studies of any wild bird.

“We know more about this population than you can know about most birds,” Fitzpatrick says. “Take Blue Jays—they’re everywhere, but they’re incredibly hard to study. They nest thirty feet up in a tree, and they fly all over the place. It’s a nightmare.”

Florida Scrub-Jays, by comparison, are spectacularly easy to study, he says. Nesting birds are so docile that workers occasionally lift a bird off the nest to check its contents—without provoking so much as a peck or squawk. And they are sedentary: most Florida Scrub-Jays spend their entire lives without ever leaving sight of the bush where they were born.

For almost 40 years, researchers at Archbold have conducted monthly counts of every bird on their main study area. They’ve found every nest, banded every nestling that survives to 11 days old, and tracked the movements and breeding success of every jay on their site. (The team also periodically searches for missing jays in pockets of scrub in the surrounding countryside.)

“We know a lot about whole lifetimes of jays,” Fitzpatrick says. Some live 15 years, and the researchers can tally up their reproductive success each year and relate it to environmental conditions or the choices birds made about where to live. “We can measure how well they’ve done,” he says, “and the currency we use is how many young they leave. That’s the only long-term currency there is in nature.”

Time and again, Fitzpatrick’s records show Florida Scrub-Jay success lies in staying close to home: birds that live just one or two territories from where they were born produce more young than birds nesting just five territories away. And in the rare circumstances in which a young jay inherits its natal territory from a parent, those birds are the most successful of all. Fitzpatrick attributes it to a sort of home-court advantage: “They know the area; they know their neighbors. They know the best places to look for and to bury acorns.” And the farther afield they venture, the more unfamiliar it is.

Scrub is such an uncommon habitat that jays pack themselves into every last corner they can find. There’s not enough land to go around, so it’s common for three or more jays—usually relatives—to share a single 20-acre territory (roughly the size of a Wal-Mart parking lot). But only two birds on each territory breed; the others just help out while they wait for a vacancy to open up on a nearby territory, practicing how the breeders do things. Chores include feeding nestlings, storing acorns, watching for predators while the rest of the group forages, and chasing away trespassing neighbors.

Despite all the help, the scrub-jay’s life is filled with disappointments. Most eggs become snake food, according to Fitzpatrick, and two-thirds of fledglings never see their first birthday. Even one-year-olds have few prospects for making a life of their own—that’s why many stay at home for a few years. Success in life hinges on becoming a breeding bird, but vacancies open up on only one of five territories per year, on average. Meanwhile, young jays have to stay alive. October and March are particularly bad, when thousands of hawks use the Florida skies as a migration highway.

But when it does come time to leave, scrub-jays rarely go far. Some 85 percent of them stay within about two miles of home, and even the females, which tend to travel farther from their natal territories than males, virtually never go farther than eight miles. The birds are dealing with the legacy of living on islands: most of the time it just doesn’t pay to leave. But every once in a while, a jay heads over the horizon and hits the jackpot: an empty territory bursting with acorns and beautiful patches of white sand in which to bury them. Whenever this “Hail Mary” strategy works, it is because of fire.

Florida is the land of the afternoon thunderstorm. Under natural conditions, lightning-ignited fires would burn off the cluttered scrub every decade or two. The vegetation expects it: scrub oaks and saw palmettos have stout underground stems that hide their vital tissues in the cool ground. Fires may devour leaves and blacken every visible twig, but palmettos put out new leaves in a matter of days. Scrub-oaks ramp up acorn production in the years after a fire. It’s as if the landscape shrugs its shoulders, stirring up the resident jays and reshuffling their territories. A few years later, those few jays that tried the Hail Mary strategy strike it rich. But nowadays most wildfires are quickly suppressed.

In 1990, Fitzpatrick and Woolfenden tried an experiment. They chose a patch of scrub that had been steadily losing jays for nearly a decade. In that time, scrub-oaks, sand pines, and palmettos had grown into dense thickets, providing hiding places for snakes and hawks, and tendrils crept over the bare sand where the jays used to bury their acorns. The researchers burned the patch to the ground, then monitored it over the next 18 years. Jays started to return almost overnight.

Another decade later, 20 jay families breed in scrub that had been virtually empty. And when Archbold fieldworkers tried to read the bands on the new jays’ legs, they discovered that 80 percent were from parts unknown. They had arrived from far away, scoring empty, productive territories while nearby jays had stuck close to home and fought with their neighbors. The Hail Mary strategy had won out for a few hearty colonists.

That fire experiment is a textbook example of the insights to be gained from long years of meticulous fieldwork. Still, it took Woolfenden and Fitzpatrick more than a decade to gather their first dozen or so records of scrub-jays moving farther than eight miles. Genetic analyses now offer glimpses of a population’s past movements from just a few drops of blood. Coulon’s work broadens the researchers’ view from the 3,700-acre study site at Archbold to encompass the entire range of the species.

This genetic approach works because when a jay makes the jump to a new area, it carries its own unique assortment of gene varieties along with it. If the jay succeeds in breeding, those new varieties enter the local gene pool, which then becomes a bit more similar to the gene pool of the immigrant’s home. The more sharing of immigrants, the more genes two populations will share, in much the same way that blue eyes are easier to find across Scandinavia than across southern Europe.

Coulon’s research employed a detailed version of this approach. To begin with, a research team headed by Reed Bowman, Woolfenden’s successor in the Archbold Bird Lab, collected blood samples from thousands of Florida Scrub-Jays across the state. Lovette’s team at the Cornell Lab then sequenced 20 regions along each jay’s DNA. With these data, Coulon used sophisticated computer programs to reconstruct which populations had historically traded immigrants.

To explain, Coulon sits in a conference room at the Lab of Ornithology and draws circles around jay populations on a map of Florida. The jay groups look like flecks of pepper scattered across the map, and the circles are a Venn diagram of scrub-jay dalliances: groups inside the circles tend to visit each other. Those outside don’t.

Coulon’s pencil indicates one broad grouping of five scrub-jay populations northeast of Tampa. The DNA evidence shows that jays have regularly moved among these groups even though they are up to 30 miles apart—four times farther away than 95 percent of jays ever go. Coulon thinks the finding represents the predevelopment era, when scrub filled the intervening spaces and jays could cover the distance gradually over several generations.

On the east coast, near Cape Canaveral, her pencil circles another curiosity: a clear line between two populations separated by only about a mile. She sees this as confirmation of the jays’ intrinsic reluctance to move across unfamiliar habitat. The two populations lie across a narrow inlet of salt water. Elsewhere, Coulon says, other sharp delineations show jays are similarly unwilling to fly across rivers and marshes.

These results point to two lessons for conservationists, one practical and the other philosophical. The genetic links between populations on Coulon’s map refine Fitzpatrick’s field data on jay dispersal, and they suggest where scrub restoration would be effective. Saving scrub between jay groups within the same circle is a better bet than working on land outside a circle.

The second insight is a reminder not to write off any population entirely. In the past, some have suggested concentrating resources to save jays in only a few of their strongholds, such as Archbold Biological Station and surrounding areas, Merrit Island on the east coast, and the Ocala National Forest. Such a strategy assumes scrub-jay populations are like checkers: scattered across a game board but basically interchangeable. Coulon’s work has shown that the populations are individually distinct. They’re much more like chess pieces: lose one and you’ve lost a part of the game that you can’t replace.

For Coulon, there’s an irony in her projects on roe deer and scrub-jays. Her work in France focused on a common animal that was incredibly difficult to catch and to follow; her goal was to understand how to manage the species’ growing population. In Florida, everything was reversed. In the field, she was bombarded by jays expecting handouts. Yet she was working with a species that is heading steadily toward extinction; her work was part of an urgent effort to ensure that scrub-jays continue to lend their azure flash to the dusty green scrub.

Perhaps the work will pay off. With all that’s known about the species after so much study, it will probably come down to exerting the willpower to do what scientists know is required: resist turning what’s left of the scrub into more subdivisions or citrus groves; periodically burn reserves to keep them productive; and attempt to re-establish scrub in selected areas to reconnect populations.

The balance of opinion may be shifting toward the scrub-jay. Sarasota County recently commissioned a study to determine how to keep jays from going extinct in the county, signaling a public appreciation of the species’ plight. As Fitzpatrick says, it’s no longer a fight to keep scrub as it always was.

“The pizza is gone,” he says. “We’re just trying to save the crumbs.” And if we can’t save crumbs that perch on our fingers, what can we save?

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library