Rusty Blackbirds are Rising from Obscurity but Falling in Number

By David W. Shaw

Rusty Blackbird by Sparky Stensaas. April 2, 2018From the Spring 2018 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

I was stepping gingerly across a mat of floating vegetation—the roots of sedges, grass, moss, and even a few blooming yellow buttercups tangled together, their bond just secure enough to hold my weight. The surface of the fen bounced like a waterbed. Then my right leg broke through to dangle in the cold and frightening depths. That’s when I realized, with crashing certainty, just why Rusty Blackbirds were such a mystery.

“These birds,” I muttered as I scrambled to solid ground, “are just too damned hard to study.”

That day, a decade and a half ago, I was searching for Rusty Blackbird nests in a boreal forest bog in Alaska’s interior. The vast wetland complex south of Fairbanks, along the Tanana River, is a stronghold for the species, and dozens of pairs were scattered over the study area. At the time, I was a research biologist for the Alaska Bird Observatory, and I was working with my field crew as part of a growing field effort to understand the breeding ecology of the Rusty Blackbird. There was a sense of urgency in our work, because Rusty Blackbirds were declining, precipitously. And no one had the faintest idea why.

During the breeding season, female Rusty Blackbirds are dark gray. Photo by Daniel Jauvin/Macaulay Library.

Males are an iridescent black during the spring and summer. Photo by David W. Shaw.

Rusty Blackbirds aren’t exciting to look at. In summer, the females of this medium-sized songbird are dark gray, and the males jet, iridescent black. Their only flash of color is a bright lemon eye that glows like a neon sign. The “Rusty” part of the name derives from their winter plumage, which, though hardly flashy, is mottled with dull red. They aren’t attention grabbing, and they don’t show up on the glossy covers of wildlife magazines. Even among birders, Rusty Blackbirds are often overlooked.

Therein lies the problem.

For decades, as the population of Rusty Blackbirds collapsed, no one noticed. Their summer homes in remote boreal wetlands are rarely surveyed, and in winter they are scattered across the swamps, suburbs, and agricultural areas of the southern United States. Summer and winter, they are a bird species largely ignored.

That changed in 1999 when the scientific journal Conservation Biology published a paper entitled On the Decline of the Rusty Blackbird. Written by the late, great, Smithsonian ornithologist Russell Greenberg and his coauthor Sam Droege of the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, the paper compiled data from Christmas Bird Counts, Breeding Bird Surveys, references to the species in the literature, regional checklists, and historical surveys. When combined and modeled over time, the data clearly showed that Rusty Blackbirds were in the midst of a mysterious collapse. Since the mid-20th century, Rusties had lost 90 percent of their population, Greenberg and Droege estimated.

Now, nearly 20 years later, scientists understand a bit more about why these cryptic blackbirds of boreal wetlands are disappearing. Yet the conservation answers, like the birds, are both hard to find and easy to overlook.

Unraveling the Mystery Behind Rusty Declines

“With Rusties, we were starting at square one,” says Dean Demarest of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Atlanta.

Demarest sits on the steering committee of the International Rusty Blackbird Working Group, a loose collaboration of researchers and conservationists in the United States and Canada who came together in 2005 to study the species, raise awareness, and understand their mysterious decline.

“One of the biggest accomplishments has been engaging researchers, graduate students, and the public,” he says. While Demarest has worked to garner financial and public support for Rusty Blackbirds, and to facilitate the research effort, it’s the ecologists in the field who started piecing the mystery together.

Steven Matsuoka of the U.S. Geological Survey led the first field efforts to study Rusty Blackbirds near Anchorage, Alaska, around the turn of the millennium. He has continued to study the birds over the past two decades. In addition to being a field biologist, Matsuoka is also an innovative songbird ecologist who uses advanced statistical modeling. If anybody knows about a smoking gun for Rusty declines, it’d be Matsuoka.

“I don’t think there’s a smoking gun,” Matsuoka said. “It seems to be many things…” He paused: “There’s a lot going on with Rusties.”

As Matsuoka says, Rusty Blackbirds have it coming at them from all directions. Polluted rainfall, climate change, habitat loss, and even blackbird control programs have taken a toll on the species. The population, he says, is still in collapse.

“The half-life of the Rusty Blackbird is about 19 years,” he said, citing a statistic from the bird conservation group Partners in Flight. In other words, in 19 years Rusties will lose another 50 percent of their population if current trends continue. PIF estimates the overall Rusty population at about 5 million birds, which sounds like a lot—but it’s one-fifth the population of Eastern Meadowlarks, and less than 1 percent of the number of Red-winged Blackbirds in North America.

“They are now so rare that they are hard to survey,” said Matsuoka. “That makes estimating populations, and management, difficult.”

More On Rusty Blackbirds and Pollution

While Matsuoka is hesitant to offer a specific cause for the decline of Rusty Blackbirds, other researchers are more willing to lay blame.

“I think it’s safe to say that methylmercury contamination is playing an important part in the decline of Rusty Blackbirds,” said Dr. David Evers of the Maine-based Biodiversity Research Institute. Evers analyzed the contaminant load of Rusty Blackbirds across their range by comparing feather and blood samples from breeding blackbirds in Alaska and northeastern North America. He found elevated levels of methylmercury in the eastern breeders.

Mercury in the environment comes from a number of places, but coal burning power plants are one of the biggest sources. Vented into the air with the fumes, mercury attaches to water and falls with rain. After it reaches the ground, the mercury is converted by microorganisms in the sediment into CH3Hg—the far more toxic methylmercury.

Methylmercury does not break down easily in the environment, and it bioaccumulates, or works its way up the food chain. The coal-generated electricity that powers the industrial hubs of the Midwest and East have led to high levels of mercury contamination in rainfall throughout the northeastern United States and eastern Canada. That mercury, deposited from raindrops above into the boreal wetlands of the region, becomes the toxic methylmercury. In short order, the poison works its way into aquatic invertebrates and from there into Rusty Blackbirds.

“Songbirds, in general, are sensitive to mercury contamination,” Evers said. Despite their small size, insectivorous songbirds (or birds that eat insects) are relatively high on the food chain. Since mercury increases by an order of magnitude with each link, even small-bodied birds can accumulate high levels of methylmercury as they eat more and more insects.

Surprisingly, though, Evers isn’t lamenting a doom-and-gloom future of abandoned Rusty Blackbird nests and mercury-poisoned chicks.

“I’m optimistic about the future of Rusty Blackbirds,” he said. “The United Nations Minamata Convention on Global Mercury went into full effect in 2017, and it’s strong enough that global mercury pollution should be dramatically reduced.”

The Minamata Convention, named after a famously toxic Japanese city, mandates a global reduction in mercury pollution. Even under the current deregulatory political climate in the United States, Evers contends there is enough momentum in the agreement to substantially reduce global mercury levels.

Rusty Blackbirds, Evers predicts, should squeeze through this pinchpoint with peak levels of methylmercury in the environment already in the past.

“I’m a hopeful person,” Evers said. “I think nature is resilient.”

Bird biologist Chris McClure has a different perspective about Rusty Blackbird declines.

“I think it’s certainly a climate-change thing,” said McClure. Though he’s now the director of global conservation science for the Peregrine Fund, McClure’s doctoral research in the late 2000s looked into the decline of Rusties.

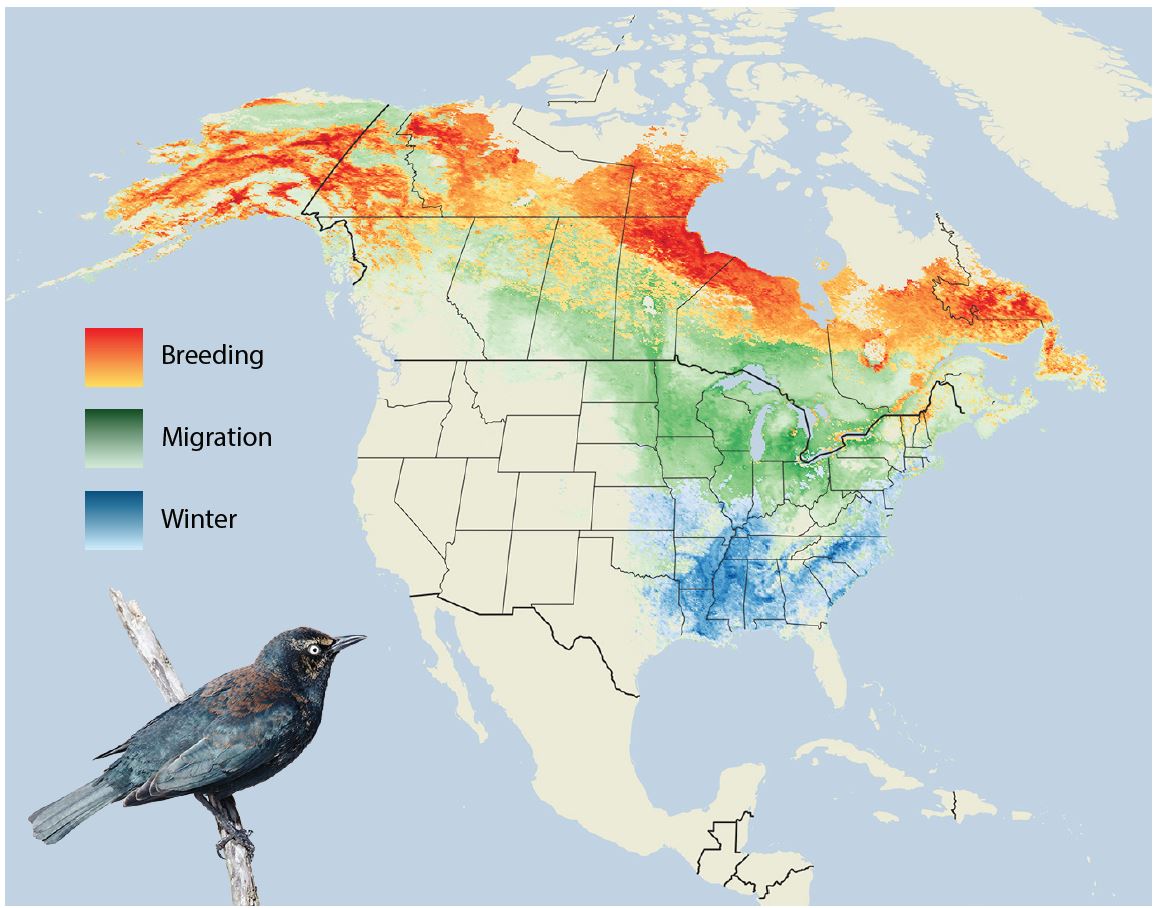

McClure’s work, published with coauthors in the journal Ecology and Evolution, contains a distressing figure— a map, based on Breeding Bird Survey routes, that shows how Rusty Blackbirds have been extirpated across the southern part of their range over the last few decades. Wetlands in the southern boreal forest have been hit hard by industrial development and habitat loss during this time.

Since the mid-1900s, 30 percent of North America’s boreal wetlands have dried up. So it’s not surprising that Rusty Blackbirds and several other bird species of the boreal bogs—including Horned Grebes, Lesser Yellowlegs, and Solitary Sandpipers—are declining.

What About Rusty Blackbird Winter Habitat?

It doesn’t get any easier for Rusties when they fly south for the winter.

Jim Johnson of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Anchorage studies Rusty Blackbird migration ecology. He has equipped birds with small data recorders called geolocators, which track where the birds go during migration. The caveat is that these recorders, which attach to the bird via an elastic harness, must be recovered to collect the data. So the same bird must be captured twice—once to outfit the blackbird with the device and again to retrieve it, download the data, and see where it’s been.

That second capture has proven tricky. After deploying 17 geolocators, Johnson and his team have recovered only three. Though a disappointingly small sample size for their effort, the data do hint at something interesting.

“All three of these Rusty Blackbirds,” Johnson said, “made a lengthy mid-migration stop on their way south.”

These three blackbirds all bred in Alaska, migrated south, and paused for a few weeks in the eastern Great Plains before moving on to their primary wintering grounds in the lower Mississippi Valley. Johnson and his collaborators are continuing their research to better understand these mid-migration stops, and whether masses of Rusty Blackbirds are making them. But the initial findings raise the possibility that prairie wetlands are an important part of the Rusty Blackbird’s migration strategy, and thereby also important for conservation of the species.

Meanwhile, on the wintering grounds, things are getting weird. Rusty Blackbirds are assumed to be wetland dependent. But the dissertation work of Patti Wohner, who studied Rusties while earning her PhD at the University of Georgia, throws swamp water at that assumption.

“Their main food sources on my study area (in South Carolina) were pecans and earthworms,” said Wohner. Pecans?

“Big flocks were associated with pecan trees in suburban areas and also in commercial pecan groves,” she said. Rusty Blackbird bills aren’t strong enough to crack the tough shells of the pecans, so the birds concentrated in places where the nuts fell on driveways or roads. After passing cars crushed them, Rusty Blackbirds moved in to forage on the broken pieces.

“The sites where the pecans were available were relatively rare, but important,” she said.

Worms, such as nonnative night crawlers and native red worms, made up the other part of the Rusty Blackbird’s winter diet. Rusty Blackbirds were unexpected early birds in the suburban yards of homes around Greenville, South Carolina.

“It seems,” Wohner said, “that suburban areas are good habitat for Rusties as long as they had three things: a nearby wetland of some type, pecan trees, and grassy areas where there was a source of earthworms.”

Wohner is another optimist about this species.

“Overall, the Rusty Blackbirds I studied seemed to be doing quite well.”

A Thousand Cuts

The eastern breeding population is being hit the hardest, perhaps by a combination of methylmercury pollution and climate change. The species may have a unique migration strategy, which raises conservation questions during their spring and fall journeys. And on the wintering areas, the species takes advantage of opportunistic foods and habitats and seems to be doing fairly well.

So where does that leave the outlook for the bird? As I reflect on my days spent splashing through boreal bogs, slogging through some of the first fieldwork on Rusties, the bits of knowledge accumulated thus far fit within a larger context. For decades, Rusties were completely unnoticed as their population crumpled. When Greenberg and Droege rang the alarm bells, scientists lacked even a basic understanding of Rusty Blackbird ecology. But over the past decade, the International Rusty Blackbird Working Group and scientists from across North America have collaborated to begin piecing the puzzle together.

In conservation science, knowledge is power. And now scientists know that the decline of the Rusty Blackbird is caused by a thousand cuts rather than a single smoking gun. While that seems much worse than a single cause, most researchers are cautiously optimistic about the ability of the species to persist in the future. Jim Johnson of the USFWS noted that recent survey data seemed to indicate Rusty Blackbird populations in Alaska and the Yukon are fairly stable and productive.

But, Johnson cautioned, the data are scarce. More science is needed, which means more scientists are needed to slog through boggy wetlands in search of the cryptic blackbird with a lemon-yellow eye.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library