Q&A: Catching Up with Christian Cooper, Host of “Extraordinary Birder”

The TV host and Cornell Lab board member shares his love of superheroes, mythology, Blackburnian Warblers, and the universal appeal of birding.

August 8, 2023

An excerpt of this article appeared in the Autumn 2023 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

“My dad gave me a pair of binoculars when I was ten years old, and I haven’t put them down since”—that’s how Christian Cooper, the cheery, bespectacled host of National Geographic’s 2023 show Extraordinary Birder, opens each episode. Skipping from one birding destination to the next, he explores places like Puerto Rico, Hawaii, and his home turf in New York City. At each stop, he goes adventuring with experts, visits conservation projects, and shares his bottomless enthusiasm for the unique birdlife he finds along the way.

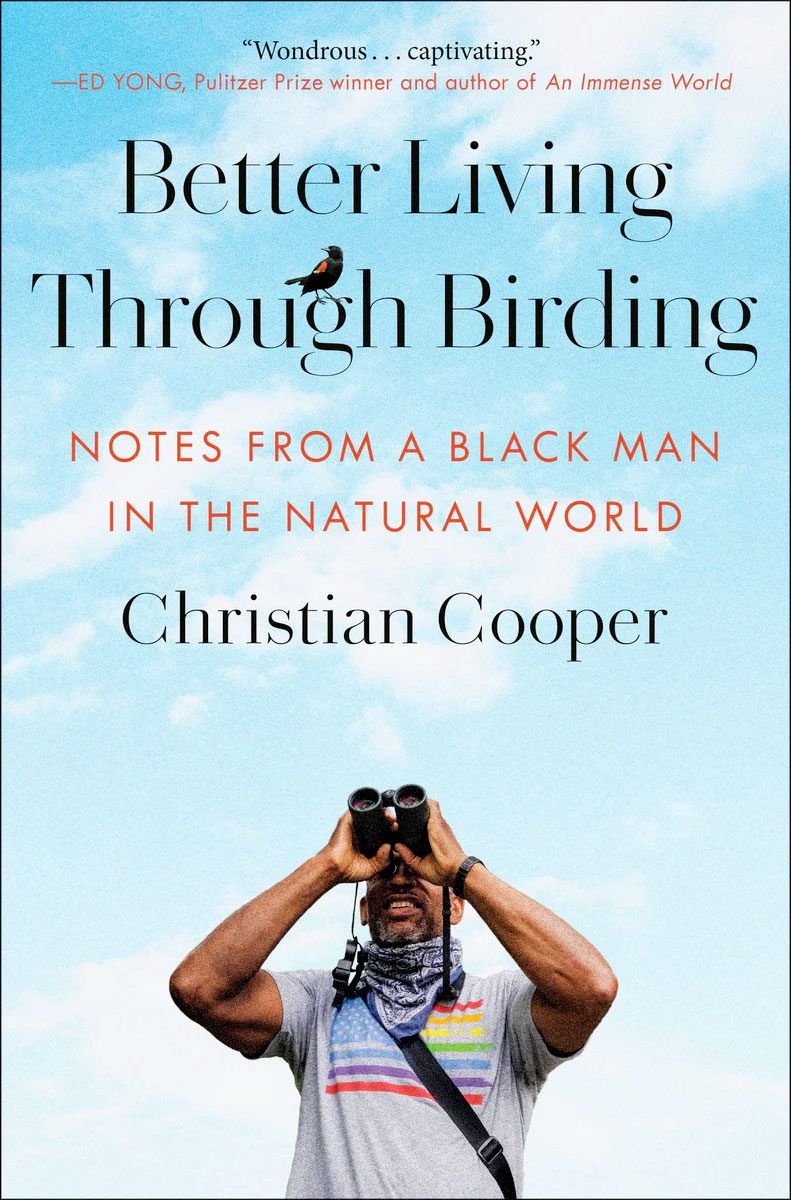

Christian Cooper wrote about his lifelong love for birds and birding in a 2023 New York Times-bestselling memoir, Better Living Through Birding: Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World. He is a Cornell Lab administrative board member and is on the NYC Audubon board of directors. We sat down with the former Marvel comics writer and editor to chat about weaving bird myths, growing up a Black and queer birder, and the universal appeal of birding.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

All About Birds: What is it about birdlife that connects deeply with you, and what about birding brings you the most joy?

Christian Cooper: The long answer is something I call the seven pleasures of birding.

Every year, I disappear during the spring migration, from the middle of April until the end of May. My friends don’t see me, and I’m not going out at night because I’m going to bed at eight. And they’re always whining about it; they ask, “Why do you do this?” This is why:

- The beauty of the birds

- The joy of being in a natural setting

- The pleasure of scientific discovery

- The joy of collecting

- The pleasures of hunting, without the bloodshed

- The joy of puzzle solving

- The seventh—this is what I call the Unicorn Effect. You know there’s a bird out there because you’ve seen pictures of it, read about it in books, seen it in the field guide, and one day you’re out there and there it is in real life as if a mythological creature has come to life.

AAB: You describe birds so vividly, like in the show you say, “If you took a ruby and infused it with so much life that it burst open, that’s a hummingbird.” In what ways does nature inspire your writing?

CC: All my spiritual inspiration comes from the natural world around me, even if it’s a sky with scattered clouds I can look at—it fills me with a sense of wonder and awe.

One of my hobbies is writing myths. One of the myths I wrote was that the goddess of the Earth was giving out all these gifts to all the different creatures of the world, and she got to the Western Hemisphere where there were all these rubies and emeralds and gems that were desperate to come alive. So, they kind of shaped themselves into birds to fake out the goddess of the Earth. She thought, ‘All right, you made an effort,’ so she poured all this energy in. And of course they’re stones, so nothing happened, but she finally poured in so much energy that they burst into life and became hummingbirds, and now they’re vibrating with energy. [Note: the full version of this story appears in Cooper’s 2014 book Songs of the Metamythos.]

So, yes, the natural world does inspire my writing and the way I think about the world.

AAB: When you talk about birding, you refrain from being too nerdy, scientific, or esoteric. Is there a reason for that?

CC: I see it as my job to translate messages. The title—Extraordinary Birder—doesn’t refer to me. What the title refers to is all those amazing people who we meet in the show, the contributors who may be birders or ornithologists or just dedicated individuals who have spent time trying to save the birds. Those are the extraordinary birders and they have a wealth of knowledge, and it’s my job to take that knowledge and bring it to an audience—and bring it in a way they can understand, appreciate, and absorb it.

AAB: In the show I see this constant stream of you drawing parallels between birdlife and human life and creating empathy that way, which I find really cool!

CC: One of my favorite parallels came in the Alabama episode. I don’t think it made it to the camera, but it’s the fact my family are all northern people for several generations. But [if] you go far enough back in the family history of any African American, our roots are in the South. I’d never been to Alabama, so I went down and it was such an amazing, eye-opening experience in so many ways.

My dad’s side of the family, the Coopers, had left Alabama. And we went north during what’s known as the Great Migration [beginning in 1910] when African Americans left the South in huge numbers to escape persecution and bigotry, but also to find economic opportunities in the North, so that your kids get raised in a better environment. That’s [similar to] what birds do every year!

The birds are wintering in the south. They leave the south to come to the north because there’s [seasonal] opportunity, because there’s a chance to raise your young where they will maybe be more successful—so it’s not an accident that the same word migration is used when you’re talking about birds seasonally and when you’re talking about African Americans who left in this period of time for opportunities in the north.

So, I love it when you can find things like that, but you can’t force it—it’s either there or it’s not. If it’s there, I try to bring that out.

AAB: I think it’s beautiful how you’re drawn to unconventional birding narratives in the show, too.

CC: I think it shows the ways that birds and birdlife are woven into our everyday lives and through everybody’s everyday lives. So with the show, you’re always spotlighting, yes, many white guys who are birders, and white women who are birders, but also other women who are birders. In the Palm Springs episode, we have a Black woman biologist. In the Puerto Rico episode, we have a blind guy who’s a birder and it gives me a chance to explain one of the reasons why we use the term “birder,” [because people can enjoy birds in more ways than just watching] and just the idea that birding is for people in all walks of life—queer, trans, everybody—birds don’t care!

As we all know, there is a big deficit in Black and Brown people birding in this country, and elsewhere… I’m hoping that by being the face of the show, a lot of Black and Brown kids will tune in and say, “He’s doing that? Oh! I can do that too!” It’s so much easier to imagine yourself doing something if you can see someone who looks like you doing it.

AAB: In your memoir, you name one of the first chapters “An Incident in Central Park.” But instead of it being about that notorious altercation in 2020, it’s a beautiful narrative of how you spotted a very rare Kirtland’s Warbler in Central Park two years earlier. Why is it important for you to not be known from the origin story of the Central Park incident?

CC: Well, because it’s not my origin story. If you want to draw a superhero parallel: Spider-Man’s origin story is when he gets bitten by a radioactive spider, but he didn’t get famous until what made him famous in the comic. It’s like that. The incident at Central Park made me gain prominence, but it is not what I do—it was maybe 4 minutes.

There’s a whole bunch of things I’ve been fighting and working for for years and years before the incident, mainly justice for Black people, equality for queer people, and the joy of wild birds for all people!

AAB: What things have helped you navigate the mostly white, straight birding community?

CC: I think having a mentor who really made it his business that my interest in birds got nurtured and that I felt welcomed regardless of the fact that there weren’t any other Black people in the group. I had this mentor, Elliott Kutner, from the South Shore Audubon Society, one of the founders of the society who led the Sunday bird walks. And when this little 9- or 10-year-old showed up on one of the walks, his eyes glowing with passion for birds, he took one look and literally and figuratively took me under his wing!

AAB: It’s really important to have even one person who believes in you, puts their faith in you, and puts in that effort.

CC: Yeah, definitely. And it’s something as a member of the [Cornell Lab’s] Board now I am trying to work on—reminding them that you’ve got to reach a little further beyond the usual perspectives you may be accustomed to reaching for. In terms of diversifying its vision, diversifying its staff, diversifying everything about the Lab, a lot of work to do! So, yeah, get busy, Lab!

AAB: For many people, David Attenborough is the quintessential nature show host. Is there anything about his work that inspires you or any critiques you have for him?

CC: I’m inspired by his longevity, the breadth of his reach, and now he’s taken up the mantle on climate change so that’s huge. That has the possibility of moving a lot of people into where we need them to go, so we can save what’s left of our planet, so nothing but admiration for him and what he’s accomplished.

But hey, if I’m able to depart from [Attenborough’s] tradition, you’ve got somebody Black and queer doing this now! And showing that there’s possibilities for others, great! I like to think of it as a growing pie rather than a limited pie. It has to be—if we’re going to save the planet. It absolutely has to be.

AAB: Are you down for a rapid-fire, of sorts?

CC: Let’s do it.

AAB: You’ve expressed a lot of praise for your spark bird, the Red-winged Blackbird. Other birds you hold dear to you?

CC: Blackburnian Warbler. That bird just ignites a passion in me. Golden Eagles, which I won’t get to see much, being in New York most of the time, but I will typically make a pilgrimage up to Oneonta [New York] to Franklin Mountain Hawkwatch, and I’ll wait for a day at the end of October or beginning of November when a cold front has moved in from the northwest, because it’ll push migrating Golden Eagles right through that gap in the mountains and it’s like the E-ZPass lane on the Golden Eagle superhighway.

AAB: Any books or birders or writers that inspire your work?

CC: I would say Professor J. Drew Lanham of Clemson University. He’s been a big inspiration to all of us Black birders, because he articulates so much about our experience so beautifully and poetically.

Essays by J. Drew Lanham

AAB: If there was a bird you could rename, which one would it be?

CC: It would be the scientific name of the Blackburnian Warbler. Which is Setophaga fusca— fusca means drab, or dull. “[So] wait, you took a bird with a fiery yellow-orange throat, and you called it Setophaga fusca?” I’d change it to Setophaga fieria! Or Setophaga solaria!

AAB: What would be your advice for your young birder self?

CC: It’s okay to be a nerd. It’s okay to be the guy who runs around looking at birds and nobody else at school gives a damn. I realized that this is what brings me joy, this is what I’m about, and I’m going to stick with it. And that was maybe the best choice I ever made.

Pareesay Afzal’s work on this article as a student editorial assistant was made possible by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Science Communications Fund, with support from Jay Branegan (Cornell ’72) and Stefania Pittaluga.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library