Patterns in Nuthatch Migration Emerge from Citizen-Science Data

By Marc Devokaitis

White-breasted Nuthatch. Photo by Zane Shantz/Macaulay Library. October 13, 2021Long known in Red-breasted Nuthatches, irruptive movements are beginning to be detectable in their close relative the White-breasted Nuthatch as well, thanks to citizen-science data.

From the Autumn 2021 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

In the fall of 2018, Red-breasted Nuthatches were going places.

On one morning in Cape May County in New Jersey, birders Michael O’Brien and Doug Gochfeld tallied a total of 1,570 Red-breasted Nuthatches zooming past their count site in just under four hours—the highest number of the species ever recorded on an eBird checklist. The hungry birds were escaping the boreal forest’s subpar crop of fruit, seeds, and cones and spilling south across wide swaths of the U.S. to find food in the woods and at backyard bird feeders.

That’s not surprising, as Red-breasted Nuthatches are a classic irruptive species. According to Birds of the World, the Red-breasted Nuthatch is “unique among North American nuthatches… as the only species to undergo regular irruptive movements that appear to be primarily driven by a shortage of winter food on the breeding grounds.”

Recent research shows that a rewrite of that passage may be in order, however. Because in fall 2018, the Red-breasted’s heftier cousin—the White-breasted Nuthatch—was on the move, too.

On the morning of October 25, 2018, Andrew Dreelin was counting migrating songbirds along the Atlantic coast at Cape May Bird Observatory in the farthest reaches of southern New Jersey, part of his duties as New Jersey Audubon’s official morning flight counter for the fall migration season. Over the course of several hours, he observed 21 White-breasted Nuthatches coursing along the beach among flocks of migratory birds such as Hermit Thrushes, Red-winged Blackbirds, and eight species of warblers.

“These birds [were] flying fast overhead, and on direct flight lines with dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of other birds—behaviors that clearly tell you ‘migration!’” says Dreelin, who is currently a graduate student at Northern Illinois University. eBird data confirms that a sighting of a dozen or more nuthatches in one day is anything but typical for the area. Throughout most of the year eBird records of White-breasted Nuthatch around southern New Jersey are almost all counts of one or two, usually the typical White-breasted Nuthatch probing the trunk of a tree or bounding to and from a bird feeder.

Around the same time as Dreelin’s observation, birders in other migration bird-count spots—such as Long Point Bird Observatory on the north shore of Lake Ontario and Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Pennsylvania—also documented large numbers of White-breasted Nuthatches on the move. There was even a nuthatch sighted by an ocean fisherman several miles off the tip of Long Island, the bird battling winds to try to make it back to shore.

Fast-forward two years to autumn 2020, and the nuthatch numbers hit new heights: On a morning count on October 14 at Higbee Beach, another Cape May count site, observer Daniel Irons tallied 73 White-breasted Nuthatches cruising past, an all-time record count for the species in eBird.

These pulses of migrating nuthatches in 2018 and again in 2020 prompted a team of researchers to take a closer look at patterns of White-breasted Nuthatch movement. It turns out, these nuthatch movements are regular, happening about every two years.

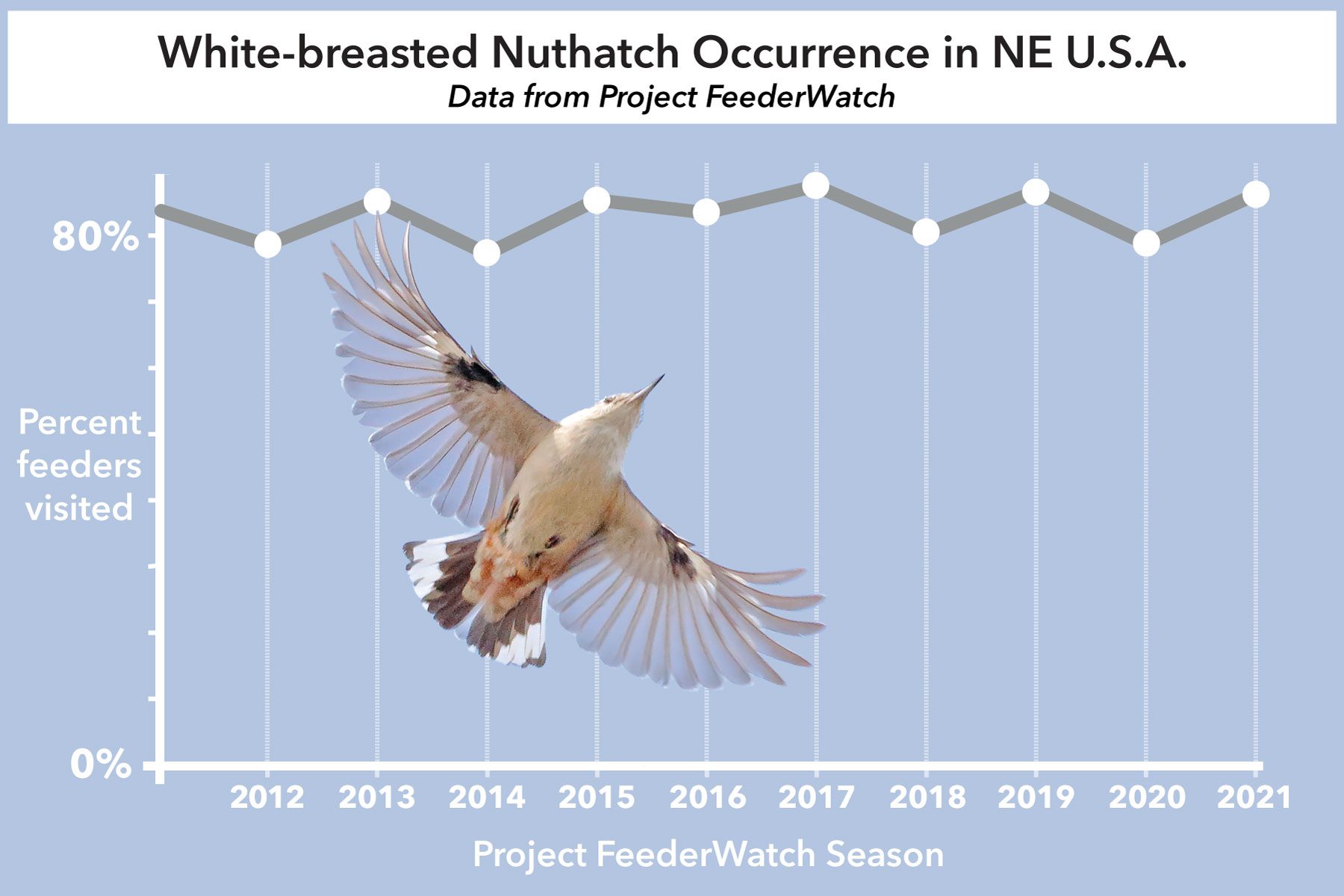

The team, which included Dreelin and other scientists from bird observatories and migration-monitoring spots in the U.S. and Canada, analyzed fall White-breasted Nuthatch migration counts from three observatories in eastern North America to confirm the every-other-year irruption. They also compared the fall migration count data to February nuthatch counts from Project FeederWatch sites across the northeastern U.S. Sure enough, the peaks in autumn at migration sites like Long Point (in Canada) were followed by an increase in the number of people reporting the species coming to their feeders at Project FeederWatch sites across the Northeast later in the winter. Paul Heveran, a research team member and undergraduate student at DeSales University, presented the results at the 2021 American Ornithological Society conference.

The researchers also compared the White-breasted Nuthatch movements to the cone, seed, and fruit crops from conifers, deciduous trees, and shrubs across Ontario—and again they found a strong relationship. In years when there was an abundance of seeds and fruit, nuthatch movements seemed to be minimal; when food was scarce, the nuthatches were soaring south, presumably in search of more plentiful food offerings. White-breasted Nuthatches feed on several different mast crops in the winter, such as acorns, beech nuts, and hickory nuts, as well as a variety of fruits and conifer seeds. Red-breasted Nuthatches, on the other hand, seem to focus more on conifers.

If the every-other-year pattern holds, scientists expect autumn 2021 nuthatch movements to be slight in comparison to last year. But Andrew Dreelin is still excited to see what the eBird data from this fall shows, even if it is an off year for White-breasted Nuthatch irruptions.

“Even though we don’t expect another big movement on the heels of last fall’s, the dynamics of irruptions are always variable and subject to change, which is what makes irruptive migrations such an exciting topic to investigate,” Dreelin says.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library