Of Dodos, Darwin, and Imperial Woodpeckers

By Tim Gallagher Editor-in-chief, Living Bird magazine July 25, 2013

Photo: Tim Gallagher/Courtesy of The Natural History Museum at Tring (pictured)

Photo: Tim Gallagher/Courtesy of The Natural History Museum at Tring

Birds-of-Paradise; photo: Tim Gallagher/Courtesy of The Natural History Museum at Tring

Type specimens, Imperial Woodpecker; photo: Tim Gallagher/Courtesy of The Natural History Museum at Tring

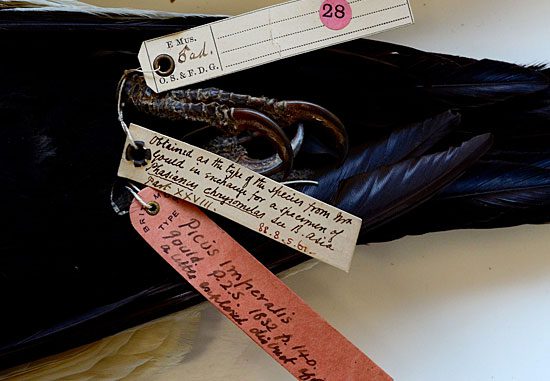

Tags on Imperial Woodpecker type specimen; photo: Tim Gallagher/Courtesy of The Natural History Museum at Tring

On a recent trip to England, I took the opportunity to explore the Natural History Museum at Tring. Although I’d visited Britain’s main Natural History Museum in South Kensington, London, several times, this was my first time at Tring, about 30 miles northwest of London, where the bird collection and ornithological library is housed.

Entering the museum is like stepping back in time to the Victorian Era as you walk past massive glass cases, framed in dark wood, containing taxidermied zoological mounts ranging from polar bears and African lions to huge raptors and spectacular birds-of-paradise. And indeed, the place was built more than a century ago, in 1889, to house the private collection of Baron Lionel Walter Rothschild, and was first opened to the public in 1892. (I’m guessing that the interior hasn’t changed much since then; it is a classic Victorian zoological collection.) The museum, with specimens and other contents, was given to the British nation by the Rothschild family in 1937, and became part of the Natural History Museum.

The museum is made up of six galleries, each housing a different set of animals. The first gallery was the most interesting to me, because—in addition to the large carnivores and primates—it has an extensive display of mounted birds, including a Great Auk, a bird that’s been extinct since the mid-19th century. I did a double take when I saw two mounted Dodos in a glass case, but they were only models. The museum does, however, have a complete Dodo skeleton.

The bird research collection and the ornithological library were moved to the museum at Tring in the early 1970s, but they are not open to the public. (Fortunately, there are plenty of mounted birds to see in the public display.) Robert Prys-Jones, curator of birds at the museum, was kind enough to give me a behind-the-scenes look at the collection and let me photograph the specimens that most interested me. It was an unforgettable day.

What is most remarkable about the bird collection is that it contains so many type specimens, or syntypes—an individual or set of specimens upon which the scientific description and name of a new species is based. I was thrilled to see the first specimen of a California Condor, collected more than two centuries ago by Archibald Menzies as it dined on a beached whale on the Monterey Peninsula. Menzies was the surgeon during Captain George Vancouver’s epic voyage of discovery from 1791 to 1795. And I was delighted to see the finches and other specimens collected by young Charles Darwin during the voyage of the HMS Beagle.

But the specimens that impressed me most were four Imperial Woodpeckers once owned by famed ornithologist and bird artist John Gould, who scientifically described and named the species in 1832. He brought several specimens of this bird, “remarkable for its extraordinary size,” to a meeting of the Zoological Society of London, where they must have created quite a sensation. Gould was somewhat vague about where the birds were collected, saying only that they were obtained from “that little explored district of California which borders the territory of Mexico.” Apparently, the skins were actually collected by an Italian mining engineer named Damiano Floresi, who collected a number of birds early in the 19th century in the Sierra Madre near Bolaños, Jalisco—a long way from California.

If you’re in London sometime in the near future, I highly recommend taking a day trip to Tring to visit this gem of a museum. It’s open from 10:00 to 5:00 Monday through Saturday, and 2:00 to 5:00 on Sunday. For more information, visit the museum’s website.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library