Keeping Hope Alive For Hawaii’s Iiwi

By Kim Rogers

June 13, 2018

From the Summer 2018 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Mud caked our boots and made walking slippery, but we were trekking through the Alakai, a high-altitude plateau situated in a rainforest among bogs on Kauai, and mud was to be expected. Thankfully my companion, Lisa “Cali” Crampton, knew to bring hiking poles. Crampton has been stalking the Alakai since 2010 as project leader of the Kauai Forest Bird Recovery Project, a conservation science group charged with safeguarding the island’s eight native forest birds. Four of those eight are on the federal endangered species list, including the Iiwi—listed in late 2017, and our target bird on the survey this morning.

It was mid-February, the weekend of the 2018 Great Backyard Bird Count, and we’d ascended to 4,000 feet where the last native forest birds on the island persist. We’d already sighted the chatty Apapane, currently the most abundant of Hawaii’s famed honeycreepers. An intense crimson, Apapane are easy to spot. The same could be said of the Iiwi. Birding in Hawaii is a lesson in an artist’s color wheel. These birds aren’t “red.” The Apapane is crimson, and the Iiwi is vermilion.

Other native forest birds of Kauai include the Kauai Elepaio. Photo by Jim Denny.

The Apapane. Photo by Jim Denny.

The Kauai Amakihi. Photo by Jim Denny.

We quickly added eight more Apapane to our list along with Kauai Elepaio, Kauai Amakihi, and Anianiau—four Hawaiian endemics just a few hundred feet down the Pihea Trail from the parking lot. But we needed to head deeper into the Alakai to find Iiwi, a bird that’s experienced a 92 percent decline on Kauai over a 25-year period. At that rate, the species could be extirpated on Kauai by 2050.

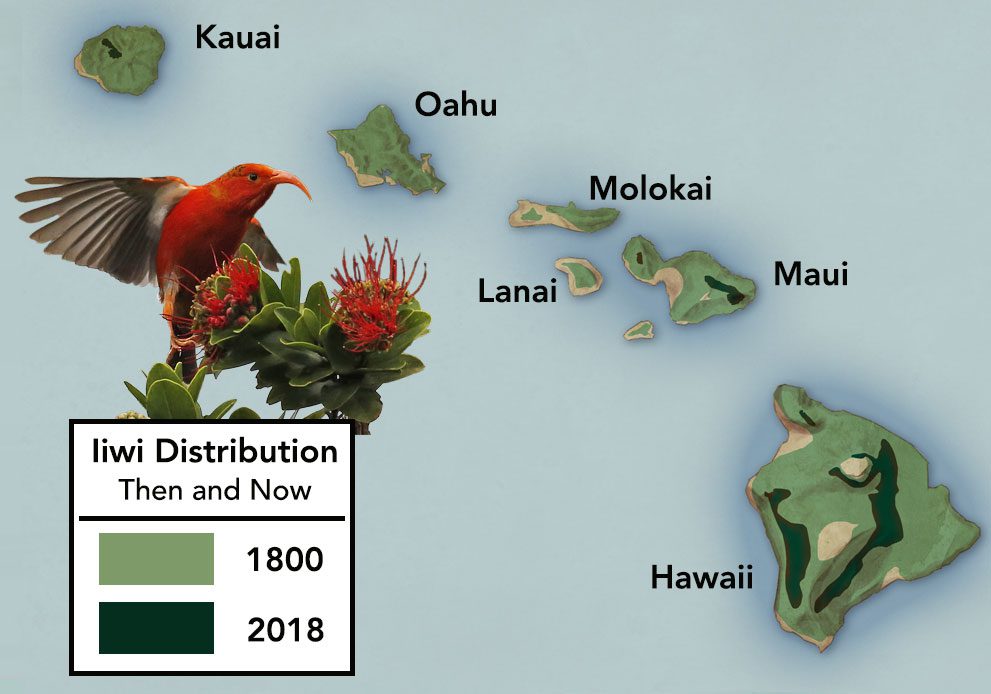

Unlike several of Kauai’s native forest birds that are confined to this island, however, Iiwi are strong fliers and over the centuries have proliferated across the Hawaiian archipelago. So Iiwi’s existence does not rely on the “Garden Island” alone. Today less than 1 percent of the population lives on Kauai.

Still, the overall rate of Iiwi population decline across Hawaii could lead to species extinction by 2100. The bird’s fate lies in the hands of Crampton and other conservationists in the state who are racing to deploy habitat restoration efforts, technology breakthroughs in the form of mosquito birth control, and new conservation strategies—all in an effort to keep this iconic honeycreeper alive well into the next century.

From Plentitude to Precipice

With its striking color and crazy scimitar-like bill, the Iiwi entices even casual birders away from Hawaii’s sunny beaches and into the mountain forests. Though there was likely a time when you wouldn’t have needed to decamp your beach mat to see it. The first historical record of Iiwi comes from Captain Cook. He described landing at Waimea on Kauai’s west side in 1778, where Hawaiians offered him Iiwi skins “tied up in bunches of twenty or more.”

Native Hawaiians made cloaks, capes, and helmets with bird feathers, with red being a treasured color for alii, the ruling class. Back then, Iiwi ranged from one end of the island chain to the other—300 miles from Kauai to Hawaii Island. Eben Paxton, an avian ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, estimates the pre-European-contact population to be many millions. In the 1890s, British naturalist R.C.L. Perkins surveyed the Alakai, just south of where Crampton and I marched through the mud, and wrote in his journal that he observed “thousands of Iiwi on the plateau in a single day.”

Even 30 years ago, Iiwi were still plentiful on Kauai. When wildlife photographer Jim Denny first started birding in the Alakai in the early 1980s, he recalls walking down the very same Pihea Trail with his camera and enjoying the “frenzy of activity and cacophony of song,” watching three or four Iiwi chase off a Kauai Amakihi attempting to feed on flowers. Then, in the late 1990s, things shifted. The amakihi could alight on those same flowers and feed unmolested. By 2005, the Iiwi failed to appear at all.

“In spite of many hours waiting by these flowers, I have not seen Iiwi on them in the last 13 years,” Denny says. “Truthfully, I find it difficult to go up into the Alakai anymore. If one searches hard enough, a few birds can still be found, but having experienced them in such abundance, it’s depressing.” The list of Hawaiian birds threatened by extinction is long, with Iiwi just the latest member of this grim and growing club. On Kauai alone, there’s the fruit-eating Puaiohi; the Akekee with crossed bill tips used to pry open buds of flowering ohia trees in search of bugs; and the Akikiki, a tiny, gray-and-white honeycreeper— all on the endangered species list, with populations of fewer than 1,000 individuals and falling.

In the last 50 years, Kauai has lost five other native forest bird species to extinction. The Aloha State is less glamorously known among conservationists as the bird extinction capital of the world, and the Hawaiian honeycreepers have been hit hard—losing over half of their 41 species in the last 200 years. Iiwi have already been extirpated on the island of Lanai, with a few individuals seen on rare occasion on Molokai and Oahu, leaving the species’ distribution to just the higher-elevation islands of Kauai, Maui, and Hawaii Island.

Iiwi and all Hawaiian native forest birds are pressured by many threats at once, including loss of habitat and predation by rats, cats, and mongoose. But most scientists agree that one threat looms largest: the mosquito.

Introduced Insects, and a Fungus, Take Their Toll

Mosquitoes aren’t native to Hawaii. In the late 1820s, as trade with the outside world increased, larval mosquitoes jumped ship from the water casks of a trading vessel from Mexico. By the mid-19th century, the invasive insect was firmly established, and the bane of humans. In 1866, Mark Twain wrote: “There are a good many mosquitoes around tonight and they are rather troublesome; but it is a source of unalloyed satisfaction to me to know that the two million I sat down on a minute ago will never sing again.”

By the turn of the 20th century, fears of mosquitoes, and mosquito-borne diseases, intensified. In 1910, The Hawaiian Gazette newspaper exclaimed: “If we don’t exterminate the mosquitoes, they will exterminate us.” Eventually, six species of biting mosquitoes would become established in Hawaii. Two—the yellow fever mosquito and the Asian tiger mosquito—are chief vectors of diseases affecting humans, including malaria, dengue fever, and Zika.

It was the southern house mosquito that swung through native birds like a wrecking ball when it started spreading avian pox in the late 1800s, then avian malaria in the 1920s or 1930s. Though deadly to birds, neither disease harms humans.

In the 1960s, biologist Richard Warner realized that native forest birds were disappearing at low elevations where mosquitoes were dense, and he implicated the two avian diseases as the culprit. Hawaii’s forest birds had no natural immunities. By the 1950s, most of the remaining disease-free habitat was above 4,000-feet elevation, where temperatures were too cold for mosquitoes to survive.

Until now.

Warming air temperatures are allowing mosquitoes to march higher and invade whatever remnant native forests are left. Crampton’s research shows mosquito larvae are now scattered across the Alakai nearly year-round. Unfortunately, given Kauai’s maximum elevation of 5,243 feet, there’s scant real estate above the upwardly creeping mosquito zone for birds to take refuge. According to a scientific paper authored by Paxton and others, it is entirely plausible that mosquito-borne avian diseases will invade nearly the entirety of Kauai’s native forest birds’ ranges by the end of the century.

This is particularly worrisome for Iiwi. When an infected mosquito slides its long proboscis deep into a bird’s skin, the unicellular microorganism Plasmodium relictum moves from the mosquito’s salivary glands into the bird’s bloodstream. One infected mosquito bite is often enough to kill an Iiwi.

At the other end of the Hawaiian Island chain, Iiwi have more room to escape mosquitoes. The big island of Hawaii has an area seven times greater than Kauai, and the tallest mountain tops out at 13,803 feet above sea level. Accordingly, Hawaii Island is now home to an estimated 543,000 Iiwi—90 percent of the species’ global population. But it’s also where a newly identified tree disease is killing off large numbers of mature ohia trees, one of the most important food sources for Iiwi and other Hawaiian forest birds. Birds slurp nectar from ohia blossoms, search its bark for insects, and nest in its canopy. Ohia are dying from a nonnative fungus called Ceratocystis fimbriata, thought to have been accidentally introduced to Hawaii via the tree nursery industry. Within just a few short weeks of the first signs of sickness, the ohia succumb to the disease, giving rise to its name— Rapid Ohia Death, or ROD.

ROD spread around the big island quickly, via automobile tires, hiking boots, landscaping tools, and even windborne sawdust from beetles that drill into the ohia trees. State officials are scrambling to develop statewide biosecurity measures to prevent the disease’s spread to other islands, though the rollout has been slow. (Before our hike on Kauai, Crampton checked the Kokee History Museum’s bulletin board for any mention of ROD and tips on how to decontaminate hiking gear. There were none.)

On Hawaii Island, conservationists at Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge have implemented their own decontamination protocols to halt the spread of ROD. As a backup plan, they have started reforesting the refuge with other nectar-producing plants that Iiwi favor.

USGS wildlife biologist Paul Banko is studying Iiwi diet on the refuge to help determine what plants would host more of the food resources that Iiwi eat. Iiwi are known to participate in a kind of seasonal migration as they chase blooming plants up and down the mountain. Those movements put the birds at greater risk of contracting disease, if they dip below the mosquito line. Banko explains his research as a key question he’s trying to answer for Iiwi: “How do you make the habitat suitable for more resident pairs, so they don’t feel like they need to move anywhere?”

Science Provides Reasons For Optimism

Despite the plague of rod and pestilence of mosquitoes, scientists in Hawaii are curiously optimistic about the Iiwi’s future. Crampton said she thought the Iiwi’s outlook on Kauai was “fair to good.” Maybe optimism is a built-in bias for those willing to work with endangered species; if there’s no hope, why bother? But Crampton and others also foresee scientific breakthroughs coming. “The prospect of getting rid of disease five, six, or seven years ago seemed impossible,” says avian ecologist Eben Paxton. “But I think we now have the tools to really address this pressing existential threat.”

The tools Paxton is referring to affect mosquitoes’ fertility. One option is a naturally occurring bacteria, Wolbachia, which can be introduced in males to make them reproductively incompatible with females. Another, more controversial, technique relies on genetic manipulation, with the goal of creating males who only produce male offspring, eventually eliminating females from the population. Both of these techniques hinge on the release of hordes of reproductively impaired mosquitoes on the landscape to instigate a population crash (this time among mosquitoes). No small feat, and one that would require a sizable chunk of financial help.

While the Iiwi’s listing under the Endangered Species Act does not automatically provide a windfall of cash, the listing does make it eligible for several sources of federal funding. But Crampton has never been one to sit around and wait for the government to give her money. A few years ago she launched a crowdfunding campaign called “Birds Not Rats” that netted $35,000 to help pay for rat traps in nesting areas where rats were raiding eggs and hatchlings. Recently, she’s launched another campaign dubbed “Save a Bird, Swat a Mosquito” to raise funds for localized control of mosquitoes, as well as for blood sampling of birds to help in some innovative scientific studies coming on the horizon.

The new research focuses on a potential solution of the birds’ own evolution. Oahu Amakihi have started nesting successfully in low elevations outside Honolulu, where mosquitoes abound. The same is happening with Hawaii Amakihi on Hawaii Island, and Apapane across the archipelago. It seems that nearly 200 years after the arrival of mosquitoes, some birds may be developing tolerances or immunity to these avian diseases. The idea is tantalizing enough for the National Science Foundation to have awarded a $2.5 million grant to a collective of researchers from Rutgers University, the Smithsonian Institution, the University of California, Santa Cruz, and the University of Tennessee, along with Paxton of the USGS.

The team is studying the genomics of the birds that appear to be tolerating the diseases and comparing them to the genomics of the vector and the parasite.

“Our hope is to use the information to facilitate evolution,” Paxton says. “You could do translocations. Maybe captive-breed malaria-resistant types of forest birds that we can release back into the wild. You could get super futuristic and think about genetically modifying these wild birds.

“To me, extinction is the worst case of anything so it’s worth entertaining a range of possibilities.”

As Crampton and I headed deeper into the Alakai, spotting more blooming native plants, we passed a fellow birder who’d seen an Iiwi not far down the trail. Walking ahead of me, Crampton suddenly stopped when something above squeaked like a rusty door hinge.

“I hear it,” she said, and pointed up.

Through an opening among the foliage, I could see the bird’s vermilion body and black wings as it perched on an uppermost branch. Then, the bird turned its head, and I could see the scimitar bill in perfect profile. Within seconds, the Iiwi launched into the air, flying 50 feet away for an ohia where a second bird joined it.

I pulled out my GPS and noted the coordinates of our location, happy to help fill in a few data points for Crampton’s research. Crampton was smiling. Each time she and other scientists see an Iiwi on the Hawaiian islands, it gives them renewed hope.

“We’ve seen many extinctions over the last 200 years, but there’s still a lot of Iiwi,” says Paxton. “We’re not talking the brink of extinction. We can do this.”

Kim Steutermann Rogers is a freelance journalist based on the Hawaiian Island of Kauai. Her work has appeared in Smithsonian.com and Audubon.org.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library