How Do Birds Survive the Winter?

Story by Bernd Heinrich; Illustrations by Megan Bishop

December 19, 2018

From the Winter 2019 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

It seems logical that most birds flee the northern regions to overwinter somewhere warmer, such as the tropics. Their feat of leaving their homes, navigating and negotiating often stupendous distances twice a year, indicates their great necessity of avoiding the alternative—of staying and enduring howling snowstorms and subzero temperatures.

However, some birds stay and face the dead of winter against seemingly insurmountable odds. That they can and do invites our awe and wonder, for it requires solving two problems simultaneously.

The first is maintaining an elevated body temperature—generally about 105°F for birds—in order to stay active. Humans in the north, with our 98.6°F body temperatures, face the same problem during winter of staying warm enough to be able to function, as anyone walking barefoot at –30°F will attest to within seconds.

The second problem to be surmounted in winter is finding food. For most birds, food supplies become greatly reduced in winter just when food is most required as fuel for keeping them warm.

One might wonder if birds are endowed with a magic winter survival trick. The short answer is: they aren’t. They solve the winter survival problem in many ways, often by doing many things at once. Although some species have devised the evolutionary equivalent of proprietary solutions, most birds follow a simple formula: maximize calories ingested while minimizing calories spent.

Black-Capped Chickadees

Chickadees (like most year-round northern birds) brave the winter in their bare uninsulated legs and feet. Yet their toes remain flexible and functional at all temperatures, whereas ours, if that small, would freeze into blocks of ice in seconds. Don’t they get cold?

They do. Their feet cool down to near freezing, close to 30°F. Of course, a bird’s comfort level for foot temperature is likely very different from ours; they would not feel uncomfortable until the point when damage occurs from freezing (ice crystal formation).

More On Birds and Winter

But chickadee feet don’t freeze, and that’s because their foot temperature is regulated near the freezing point and may stay cold most of the time all winter, even as core body temperature stays high.

Every time the bird sends heat (via blood) from the body core to the extremities, it must produce more heat in the core for replacement. Thus, if a chickadee maintained its feet at the same temperature as its body core, it would lose heat very rapidly, and that would be so energetically costly that any bird doing so would quickly be calorie depleted. Birds maintaining warm feet would be unlikely to be able to feed fast enough to stay warm and active.

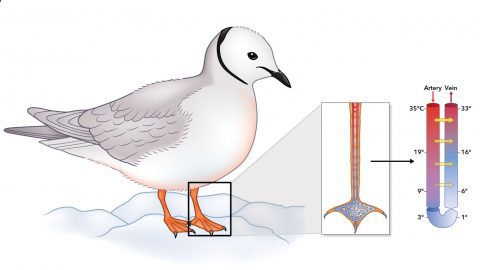

However, a chickadee’s feet are provided with continuous blood flow. The warm arterial blood headed toward the feet from the body runs next to veins of cooled blood returning from the feet to the body. As heat is transferred between the outgoing and incoming veins, the blood returning into the body recovers much of the heat that would otherwise be lost flowing out.

Birds retain heat in their body core by fluffing out their feathers. Chickadees may appear to be twice as fat in winter as in summer. But they aren’t. They are merely puffed up, thickening the insulation around their bodies. At night, they reduce heat loss by seeking shelter in tree holes or other crevices, and by reducing their body temperature—the smaller the difference in temperature between the bird and its environment, the lower the rate of heat loss. Still, the bird may have to shiver all night and burn up most of its fat reserves, which then must be replenished the next day in order to survive the next night.

Nighttime is crunch time for winter survival because no food calories are coming in to replace those being expended. It is a tight energy balance, but by lowering body temperature and turning down heat production at night, chickadees and other small birds of winter spare the cushion of fat accumulated during the day.

While physiology is a key component of surviving the cold by temperature regulation, the more critical factor is food input. That little chickadee’s internal furnace must be fed and stoked. Following chickadees in the winter woods, and watching them closely, reveals another secret of their winter survival.

Chickadees in winter travel in groups. In Maine, I seldom see them alone. Exploring for food, they appear to pick at just about everything, and when one chickadee finds something to eat, its neighbors notice and join in. All the while the chickadee winter flock learns by trial and error, and from each other.

For foraging chickadees in winter, food options are still broad—from various seeds, spiders, and spider eggs, to insects and their pupae. Invertebrates may seldom be seen out in the open during winter in the frozen North, but they’re around—hidden in the ground, under bark, even underwater—as they employ their own winter survival strategies.

Some caterpillars overwinter in a state of being frozen solid to tree branches. In one instance I found a flock of chickadees feeding on minute caterpillars hidden within the scale-like evergreen leaves of a cedar. Some lucky chickadee had discovered this cache of frozen caterpillars, perhaps with the help of a clue—a blemishing stain on the leaf from the caterpillars’ previous munching.

Golden-crowned Kinglets

These diminutive coniferous-forest gnomes (about half the weight of a chickadee) are, because of their size, the ultimate marvels in warm-blooded winter survival.

Unlike chickadees, Golden-crowned Kinglets almost exclusively eat insects for their diet, yet they are too small to handle some of the larger food items—such as a silk-moth cocoon filled with a pupa. Kinglets are not cavity nesters like chickadees, and therefore not predisposed to enter tree holes for sheltering overnight. Thus, at both ends of the energy equation—food input and heat retention—Golden-crowned Kinglets seem highly challenged. Yet I have positively identified them in the Maine winter woods at –30°F.

Various scenarios have been proposed for how these kinglets manage to survive winter, such as overnighting in squirrel nests. But having followed them many winters, I found no evidence of that. The Golden-crowned Kinglets I have observed traveled in small flocks of about half a dozen, often accompanying chickadees, yet I was never able to find where or how they spent the night. It was always almost pitch dark when I saw them last, and then they vanished suddenly. Could they have disappeared where I had last seen them?

That turned out to be the case. On one evening I saw four kinglets disappear into a pine tree. Later that night, with extreme caution and armed with a flashlight, I climbed the tree and spied a four-pack of Golden-crowned Kinglets huddled together into one bunch, heads in and tails out, on a twig. One briefly stuck its head out of the bunch, and quickly retracted it—indicating it was staying warm, and not in cold torpor.

Using each other as a heat source, as a means of reducing their own heat loss, is an ingenious strategy, as it alleviated these birds from searching for or returning to a suitable shelter at the end of the day. By traveling as a group and converging to huddle, they were their own shelter instead.

Woodpeckers

Woodpeckers have the tools and behavior to stay fed all winter. Their long, drill-bit bills and ability to cling to tree trunks and branches allow woodpeckers to access wood-boring insect larvae (Hairy and Downy Woodpeckers), and also hibernating carpenter ants (Pileated Woodpeckers). As for overnight shelter, woodpeckers do something that few other birds can do: make themselves a shelter specifically for overnighting.

Shelter-building is an evolutionary outgrowth from making a nesting cavity in spring, but their winter dens differ substantially. I usually find the first evidence of woodpecker overnight shelters after the first frosts in late October or November. On the forest floor, I look for accumulations of light-colored wood chips on top of the recently fallen leaves or on snow; then I look up.

The excavated roosting cavity is usually in a rotting snag. In contrast, nesting holes are excavated in snags with more solid wood. The winter overnight shelters are often within about 6 feet of the ground, at least three times lower than a nesting cavity. The same woodpeckers attend their same roost hole nightly and may use it all winter long.

But not necessarily. Sometimes an overnighting hole, which can be excavated in as little as a day, is only used for a few days. Existing holes are also used opportunistically; in one case I flushed both a Downy and a Hairy Woodpecker out of the same hole. Usually, though, a hole is used by only one woodpecker at a time. I suspect the woodpeckers’ shelters are so good, and their food supply so secure, that huddling in groups, as in kinglets, is not a necessity.

Ruffed Grouse

Ruffed Grouse can fly well for short distances when they have to, but they spend most of their time grounded. However, in winter their food supply is in the tops of the trees, where they feed on the buds of aspen, poplar, birches, and hophornbeam that are packed with nutrients and ready to burst into flower and leaf right after the first thaws of spring.

Winter is no time of food scarcity for grouse. A grouse in the top of a tree can pick enough buds in about 15 minutes to support its overnight needs. Similarly, at dawn it can feed again in a short time, filling its crop with enough buds to support its needs throughout the day. A half-hour is a trivial time investment in feeding, compared to a kinglet or a chickadee that can barely get enough food-as-fuel while foraging nonstop for the entire day.

Casual observers in the North Woods seldom see grouse in winter, even though grouse would seem to be hard to miss because of their large size. Bird watchers look for Ruffed Grouse at dusk and dawn, when they fly up into a tree, usually in the company of others, to quickly scarf down tree buds.

They can ingest so much food in just a few minutes because, unlike most other birds in the winter woods, they possess a large crop (a pouchlike extension of the esophagus where food can be stored). The crop is like a bag that, after being filled, can later deliver food to the gizzard for digestion throughout the day or night.

What then do Ruffed Grouse do with the rest of the winter day? For two winters I studied our local Ruffed Grouse in western Maine to find out. When there was fluffy snow, our grouse spent most of the day under the snow. The length of time they denned there could be calculated by counting poop. I found, from known snow-den residency times, that grouse produce on average 3.7 fecal pellets per hour. In one night, they produced about 60 fecal pellets, suggesting they may not just overnight in a snow den, but spend as long as 16 hours under the snow. That is, they also spent part of the day submerged.

Grouse are well known to burrow under the snow for insulation from the cold, and thus save energy. And grouse can access plenty of food, given the abundant tree buds available for them to eat. Their winter survival problem to surmount, instead, is not so much to find enough to eat, but rather not to be eaten.

Grouse are a favorite prey of raptors in the winter woods. Unlike the Arctic ptarmigans, they do not molt into a camouflage of white feathers in winter. Ruffed Grouse stay earthen-colored all year long, which makes them visible on white snow from afar. A plump Ruffed Grouse perched atop a bare tree is a convenient offering for a Great Horned Owl or goshawk. The Ruffed Grouse’s snow dens, then, may also be a means of reducing predation.

It might be supposed that small perching birds might benefit greatly from snow-burrowing as well, at least during the night. But by and large, they don’t. High Arctic–dwelling redpolls and Snow Buntings may shelter briefly under snow drifts, but no small birds in the northern United States and southern Canada den in the snow overnight.

The fact that they don’t, given the huge potential benefit from insulation, is likely explained by the potential cost. Warming on some sunny winter days melts the top layer of snow, which then refreezes into a solid seal of crust at night. A whole population of small birds over a huge area, then, could be killed in a single night—locked beneath the snow to starve and be vulnerable to subnivian mammals. The large size of the grouse not only gives it a large advantage in energy balance, relative to songbirds, but that size also makes escape from the snow easier if needed.

Crows and Ravens

Every winter crows gather by the thousands in communal roosts where they sleep at night. Come morning they sally forth on their daily excursions, but again they return in groups at night. Such roosts are often in an urban area, where masses of crows convene in the same area each winter.

Like the snow-denning of grouse, this phenomenon is unlikely to be explained by one function only. Communal roosts serve as information centers. They are where knowledge of food locations is shared, probably unintentionally, as those crows that don’t know where there is a dump or a corn field simply follow others, which then becomes the crowd. The presence of many crows together also spreads the risk of predator attack at night, as well as provides a social network for mutual warnings of danger.

Ravens are quintessential winter birds that live and thrive in winter like few others. They range into the High Arctic and begin nesting in mid-February in northern North America. Their large size is an advantage, as they have a slower rate of heat loss than other passerines. Ravens also exploit carnivores such as wolves (and perhaps human hunters), and they profit from each other’s experiences, thus pooling information.

Ravens will kill almost any animal they can catch, but given their high energy needs, surviving winter for them means feeding on the carcasses of large animals they could never kill. The raven’s carnivore connection is most prominently displayed by association with wolves. Under natural conditions, ravens arrive at and feed on wolf kills within minutes after a pack kills an ungulate, such as elk in the Yellowstone ecosystem. In other areas, a single raven may locate a carcass and return to the nocturnal roost, at which point a crowd of ravens follows the discoverer to the food bonanza.

The first fortunate raven to discover the carcass probably does not share information with its fellow ravens willingly. During the breeding season a territorial pair of ravens will fiercely defend a carcass from others. But in winter, ravens share food as a crowd. By accessing large clumped food resources, ravens can range as far north as their providers—wolves, humans, and polar bears.

Ravens, as with other corvids (and chickadees and nuthatches), also capitalize on a temporary abundance of food by caching surpluses. Storing food is an insurance policy against the uncertainty of future food availability during the lean times of snow and cold. Surviving winter is not always survival of the biggest and strongest. It is a matter of mastering the equation of energy input versus output, taking into account all of the variables and always leaving enough calories to live another day.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library