Five Things You Need to Know about Greater Sage-Grouse and the Endangered Species Act

By Gustave Axelson

September 4, 2015

On 21 September 2015, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced its decision not to grant Endangered Species Act protection to the Greater Sage-Grouse. Read our statement on the decision.

September 30, 2015, is the court-ordered deadline for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to make a final decision about whether to list the Greater Sage-Grouse under the Endangered Species Act.

At stake is perhaps the broadest application (in geographical terms) of the ESA ever. Listing the Greater Sage-Grouse would affect 165 million acres from North Dakota to Washington. By comparison, the high-profile federal listing of the Northern Spotted Owl affected forests in just three states: Oregon, Washington, and northern California.

Sage-grouse have been the subject of fierce debates in the West between energy companies and environmentalists. But those two groups—as well as state and federal agencies, private ranchers, and public land managers—have formed unprecedented coalitions to work together in recent years to keep sage-grouse off the Endangered list, in what has become the largest single-species conservation effort ever.

So how would a listing change this political balance? And if the bird isn’t listed, will any incentive remain for continued collaboration? You’ll hear plenty about sage-grouse this month as the deadline for a listing decision draws near. Here are five things you need to know as you watch the next act of the sage-grouse political drama play out.

What’s at stake?

Related Stories

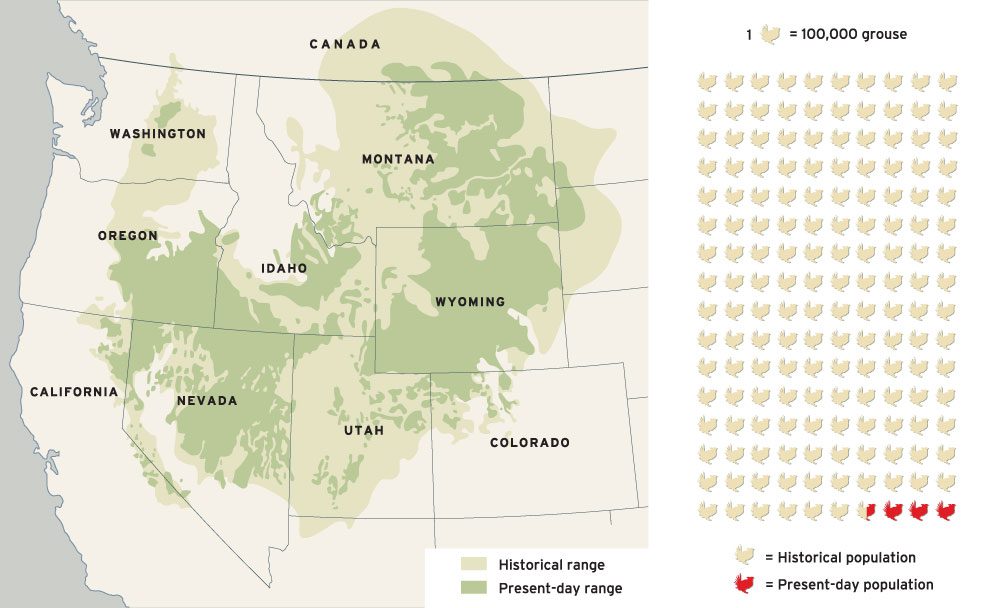

It comes down to the need to conserve a unique but imperiled species and its landscape without threatening the livelihood of people that live there. The need is acute. The range of the Greater Sage-Grouse—the sagebrush steppe ecosystem—has been severely fragmented over the past two centuries by settlement, farming, ranching, mining, sprawling urban development, invasive species, changes to fire regimes, and fossil-fuel extraction. Sage-grouse numbers have dropped from presettlement estimates as high as 16 million to a few hundred thousand today (a decline of more than 95%). According to the North American Breeding Bird Survey, Greater Sage-Grouse populations have declined by more than 60% over the past five decades.

But the range of the Greater Sage-Grouse is also an area of the West where oil and gas production has doubled since 1990. The Western Energy Alliance calculated that a federal Greater Sage-Grouse listing could cost more than $5 billion in annual economic output. A listing would also impact the cattle industry by affecting ranchers who graze their herds on millions of acres of federal land in the West.

How did the September 30 deadline come about?

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has already decided once, in 2005, that an endangered listing was not warranted for Greater Sage-Grouse, but that decision was overturned by a lawsuit and ruling in a federal court that the agency hadn’t considered the best available science. Then, in 2010, the USFWS ruled that a Greater Sage-Grouse listing was warranted but precluded by other, higher conservation priorities. That ruling was also challenged and the court ordered USFWS to either list or not list the sage-grouse, giving them until September 30, 2015, to decide.

So has this sage-grouse debate been stuck in the courts for the past decade?

No—there’s actually been a lot of conservation progress during this time. Federal and state agencies and private landowners (mostly ranchers) have developed conservation measures aimed at convincing the USFWS that an Endangered listing isn’t necessary. The Sage Grouse Initiative has restored more than 4 million acres of high-quality habitat (twice the size of Yellowstone National Park) on private lands. This program is funded by the Farm Bill through the Department of Agriculture and contracts with ranchers on easements and incentive programs. On public lands, the federal Bureau of Land Management (the biggest landowner in the West) has issued sage-grouse management plans for all 61 million acres it owns in the species’ range. Altogether, Western states have invested more than $200 million in sage-grouse, and the federal government has invested $300 million—with another $200 million on the way. The grand total spent on sage-grouse conservation is getting into the realm of building a new sports stadium.

“This whole sage-grouse deal, there’s never been a larger conservation effort on the planet directed toward a single species,” says Tom Christiansen, sage-grouse program coordinator for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department.

Who cares?

Economics aside, this is a unique species that deserves more admiration and positive attention. Some call sage-grouse “America’s bird of paradise,” because of their elaborate spring mating dances—big crowds of female sage-grouse gather in flat, open spots called leks to watch competing males. The sounds echo across the sagebrush— whoop-whoop, pop-pop—as males vigorously thrust yellow air sacs out of a billow of snow-white feathers draped around their neck. Sometimes rival males face off and flap their feathers in a wingbeat scuffles. On spring nights with a full moon, the breeding displays are so vigorous that the sage-grouse dance all night long in the moonlight.

What’s more, conservation for Greater Sage-Grouse benefits all 170 species of birds and mammals that live in the sagebrush steppe ecosystem—including other majestic species such as pronghorn and Golden Eagle. One study showed that habitat conservation for sage-grouse in Wyoming’s Green River Basin doubled the protection of mule deer migration habitat and winter range. The bird is the subject of the listing debate, but the entire ecosystem needs conservation.

So if sage-grouse get listed, is that a win for the birds? If sage-grouse don’t get listed, is that a win for people?

Popular media often characterize this issue as people and birds on opposite sides of the battlefield. But in one respect, you could say that both sage-grouse and people have already won (largest single-species effort ever for conservation, and hundreds of millions of dollars invested into the private lands of ranchers to make their land healthier).

Since the real goal of conservation is to keep a species from declining to the point of becoming endangered, a non-listing could be perceived as an indication that the Endangered Species Act is working—since the possibility of a listing has served as a powerful incentive for governments and private landowners to collaborate well in advance to conserve a species before it becomes critically at risk of extinction.

So far, the USFWS has ruled both ways on two other listing decisions related to similar species—the Gunnison Sage-Grouse was listed as Threatened under the ESA in November 2014, but in April 2015 a distinct population of Greater Sage-Grouse along the Nevada–California border was not listed, largely due to the robust conservation efforts already underway for those sage-grouse.

Whatever the final ruling, many conservationists agree progress has been made. “This ecosystem was utterly without protection 10 years ago,” Audubon Rockies vice president Brian Rutledge told the High Country News in June. “We’re a hell of a lot better off than we were.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library