FAQ: Outdoor Cats and Their Effects on Birds

Q: Is the Cornell Lab of Ornithology anti-cat?

A: Not at all. Many of our ornithologists and staff have indoor cats, and we love both birds and cats (see slideshow for examples). But the sheer numbers of cats raises a problem of responsibility, affecting not just birds but people and cats as well. In the United States alone, there are 60 million to 100 million free-ranging, unowned cats. These are non-native predators that, even using conservative estimates, kill 1.3–4 billion birds and 6.3–22.3 billion mammals each year in the U.S. alone (Loss et al. 2013, Nature Communications). As a conservation organization, the Cornell Lab recognizes that this is an unnatural situation that is taking a tremendous toll on the native wildlife of our continent. Because outdoor cats are a human-caused problem, it is our responsibility to find ways to address it.

Many people who care about cats also recognize that it’s not ideal to allow cats to roam. Outdoor cats live short lives characterized by hardship, disease, and injury. Cats suffer when they are hit by cars, injured or killed by predators or other cats, or contract diseases. Outdoor cats live less than half as long as indoor cats on average. Outdoor cats also transmit diseases such as toxoplasmosis to humans and to wildlife including sea otters and Hawaiian monk seals.

Many advocates for cats, birds, and human public health agree that it’s best for all to reduce the number of free-ranging cats, although they may disagree about the urgency or the way to achieve it. As a scientific institution dedicated to the understanding and protection of birds, it is important for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology to raise awareness of the devastating toll that cats are taking on birds, and to explain what the science is telling us about the causes and solutions—even when this raises uncomfortable questions.

Q: What is the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s position on Trap-Neuter-Return?

A: Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) refers to the practice of capturing unowned cats so they can be vaccinated, spayed or neutered, and re-released into the wild. Although in an ideal world this approach might reduce the number of free-ranging cats over time, studies have shown on-the-ground complications leading to ineffective results. Based on scientific studies about the outcomes of TNR, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology does not support TNR as a management approach to reduce the negative impacts of feral cats on wildlife.

These are some of the known problems with TNR:

- The establishment or maintenance of cat colonies encourages people to release additional cats (Castillo and Clarke 2003). In some cases, TNR may actually increase population size compared to no intervention at all (McCarthy et al. 2013).

- The high reproductive potential of cats, the effort involved in catching them, and the number of cats on the landscape combine to make it very difficult to neuter enough members of a colony to keep their numbers in check. Models show that for TNR to be successful, between 71% and 94% of all cats in the colony must be spayed or neutered. Each time a non-neutered feral cat has a litter, or someone abandons non-neutered cats at the colony, the prospects for success diminish.

- Feral cat colonies are a major part of the cat problem: feral or unowned cats are responsible for an estimated 69% of all cat-killed birds in the U.S.

- From a public health perspective, trap-neuter-vaccinate-return programs do not reduce the risk of toxoplasmosis or rabies exposure for human populations (Roebling et al. 2014). Studies show that TNR programs have been and are expected to be less effective at reducing populations of feral cats than trapping and euthanizing cats (Andersen et al. 2004, Longcore et al. 2009). One study found that trap-euthanize could extirpate a large colony within 2 years, whereas the twice as expensive TNR option was unlikely to succeed within a 30-year timeframe (Lohr et al. 2013). In cases where there is some immigration (or release) of new cats in the population, euthanasia is likely to be the most effective treatment (Schmidt et al. 2009). The National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians concluded that free-ranging feral cats and TNR programs are detrimental to public health.

- TNR does not address the risks and hardships that cats face living in the wild and that contribute to an average life expectancy of as little as 2 years, including injury, disease, predation, vehicle collisions, and maiming during cat-cat fights. Certain animal welfare groups, such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, also oppose TNR for these reasons.

Q: Why put the blame on cats when human-caused problems are so much more severe? Cats are just doing what they do.

A: It’s true that human-caused problems are the most severe, but it’s essential to recognize that cats are one of those human-caused problems. No one would argue that cats are inherently “evil” or “wrong”—but they have become a problem because humans brought them onto the continent, and because humans continue to increase their numbers by failing to spay or neuter their pets, by abandoning cats into the wild, or by providing food at feral colonies. The problem has become especially severe because of the many tens of millions of cats living in a semi-wild state within the United States alone. These cats, and the damage they do to native birds and other wildlife, are our responsibility.

Q: If you want to save birds, then you should work on the multitudes of problems humans have caused that are far more devastating to birds.

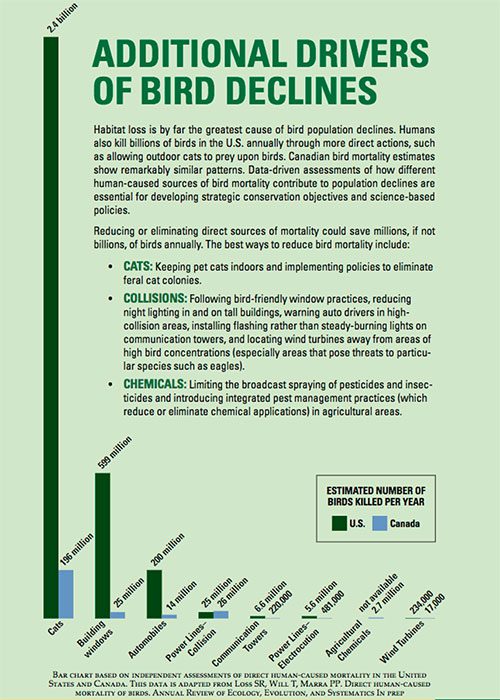

A: You are right that in order to save birds, we must address many challenges that are driving declines in birds. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology takes a multifaceted approach. Habitat loss and degradation are the biggest threats, and we work within the United States and with international partners to identify and protect critical areas for birds. In North America, cats are second only to habitat loss as the largest human-related cause of bird deaths. It’s estimated that cats kill 1.3–4 billion birds each year in the U.S. alone, with 69% of these kills attributable to feral or unowned cats. This is a staggering number even when compared with the next-largest sources: 599 million estimated to be killed in collisions with windows and 200 million killed by automobiles.

Q: I don’t believe those estimates of cat kills. The numbers are too large—wouldn’t birds be extinct by now if the toll were really that large?

A: The estimates are on target, using the best available numbers. The total is large because of the sheer number of cats in the U.S. that hunt outdoors—up to 100 million unowned cats plus about 50 million owned cats that are allowed outside. The model that produced these estimates actually uses fairly low estimates of any individual cat’s effect—30 to 48 birds per cat per year, for unowned cats; a lower estimate for owned, outdoor cats.

We really do hear from people who feel that these estimates can’t be true because if they were, all our birds would be dead by now—that’s how hard it is to comprehend losses on the scale of billions. Fortunately there are still several billion birds in North America, and they reproduce each year, helping to partially offset predation. But this is exactly our concern: birds can’t continue to absorb this level of predation indefinitely. We need to address the problem before it’s too late.

Scientific studies on islands enable a close-up look at the impact that cats can have on wildlife. A review by Felix Medina and coauthors in Global Change Biology found that cats have caused declines, smaller distributions, or extinctions of 175 species of reptiles, birds, and mammals; 123 species of birds have been negatively impacted, and these are likely to be underestimates because the studies were limited to just 120 of the world’s islands. Although island bird species are generally more vulnerable than those on mainlands, one-third of all North American bird species (432 species) are in need of urgent conservation action, according to the 2016 State of North America’s Birds Watch List. Aside from habitat loss and degradation, cats are by far the largest source of human-caused mortality for birds (as the graph in the above answer shows).

Q: Is there any common ground between pro-cat people and pro-bird people?

A: We absolutely believe there is common ground between pro-cat and pro-bird sides. Both sides of the debate are made up of people who are pro-animal and pro-nature at heart. People on both sides agree that much of the current problem is rooted in irresponsible or underinformed pet ownership. We encourage you to talk with others about the value of spaying and neutering pets, the importance of never abandoning cats or releasing them into the wild, and the benefits of adopting or rescuing cats—it’s rewarding for both homeless pets and the people who take them home. Another issue both sides agree on is that there needs to be a humane solution—for both cats and the birds they hunt.

We also suggest that at its core, keeping cats indoors is a pro-cat stance, because it avoids the well-documented problems of predation, violence, car collisions, and disease that afflict all outdoor cats and shorten their lives.

Q: Why shouldn’t I let my cat outside?

- Cats are not native to North America. Because of the help they receive from humans, they exist at much higher densities than native predators such as hawks, owls, and foxes do. This means that their effect on native animals is much higher than the effect of native predators.

- An outdoor cat can contract or transmit diseases and parasites including toxoplasmosis, rabies, feline leukemia, feline immunodeficiency virus, feline herpes, tapeworms, and fleas.

- An outdoor cat lives less than half as long on average as an indoor cat.

- Outdoor cats roam across property boundaries and can be a nuisance to your neighbors and a menace to birds and other animals in their yards. Stray cats can be just as disruptive to a neighborhood as any other types of stray or free-roaming pet.

- Outdoor cats hunt by instinct even if they are not hungry. Even well-fed cats are a danger to native animals. This is also why it’s a bad idea to provide food to unowned or feral cat colonies.

- Bells, cat bibs, and similar items typically do not eliminate successful hunting by cats.

Q: What are some ways to entertain my cat without letting it outside?

- Play with your cat.

- Consider adopting another cat as a playmate.

- Construct a “catio” or enclosure that allows your cat to experience the outdoors without becoming a danger to native animals.

- Take your cat for supervised walks on a leash. Though this approach is not for all cats, some really enjoy it.

Q: Instead of inviting just the author of Cat Wars to give a Monday Night Seminar, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology should have invited a speaker with an opposing viewpoint.

A: The Cornell Lab of Ornithology welcomes the audience to respectfully discuss opposing and diverse viewpoints during the question and answer period after every Monday Night Seminar. These one-hour seminars offer the opportunity for scientists and other speakers to share their views. The views of invited speakers are not necessarily those of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology or Cornell University. It’s our hope that the audience will take the opportunity to listen to what speakers have to say and engage in respectful dialogue after the talk. Watch the seminar Cat Wars Author Pete Marra Discusses The Effects Of Outdoor Cats On Birds.

Q: I read that Cat Wars author Peter Marra says free-ranging cats should be removed “by any means necessary.” Is that true? I think that’s unethical.

A: Dr. Marra’s comments were taken out of context. This is the complete statement from the book:

From a conservation ecology perspective, the most desirable solution seems clear—remove all free-ranging cats from the landscape by any means necessary. But such a solution is hardly practical given the legions of cats roaming the land—as many as 100 million unowned animals, plus the 50 million owned cats that roam—and the painful question of what to do with the cats even if they could be captured.

When asked by the American Bird Conservancy what the solutions are, Dr. Marra stated, “There are no simple solutions. We have worked our way into a bind by allowing such irresponsible behavior with an invasive predator. Whatever the solution, it needs to be humane. We first need to put an end to the idea that it’s okay for owned cats to be let outside. For unowned cats the situation becomes more complicated. First, we need to identify the areas where cats pose the greatest risk—to biodiversity and to human health—and are in the greatest danger themselves. Cats need to be removed from these areas immediately. Once they’re removed, they can be adopted, put in a sanctuary or, as a last resort, euthanized.” Read the full Q&A with Dr. Marra on the American Bird Conservancy’s web page.

Q: Where can I learn more about how cats are affecting bird populations, and what to do about it?

A: For more information, please visit the American Bird Conservancy’s website on Cats Indoors and their Q&A with Peter Marra.

We also recommend the book Cat Wars by Peter Marra and Chris Santella. This book delves into history, culture, science, and consequences of our relationship with cats and their impact on birds. You can help by keeping cats indoors and raising awareness in your neighborhood and community about the impact of free-ranging cats on birds and other wildlife.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library