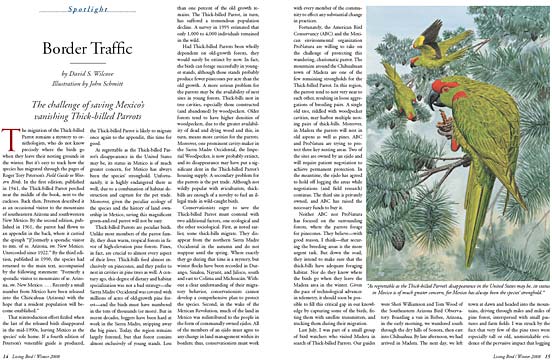

Border Traffic—Conserving Mexico’s Thick-billed Parrots

By David Wilcove; illustration by John Schmitt January 15, 2008

The migration of the Thick-billed Parrot remains a mystery to ornithologists, who do not know precisely where the birds go when they leave their nesting grounds in the winter. But it’s easy to track how the species has migrated through the pages of Roger Tory Peterson’s Field Guide to Western Birds. In the first edition, published in 1941, the Thick-billed Parrot perched near the middle of the book, next to the cuckoos. Back then, Peterson described it as an occasional visitor to the mountains of southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico.

By the second edition, published in 1961, the parrot had flown to an appendix in the back, where it carried the epitaph “[f]ormerly a sporadic visitor to mts. of se. Arizona, sw. New Mexico. Unrecorded since 1922.” By the third edition, published in 1990, the species had returned to the main text, accompanied by the following statement: “Formerly a sporadic visitor to mountains of se. Arizona, sw. New Mexico. . . . Recently a small number from Mexico have been released into the Chiricahuas (Arizona) with the hope that a resident population will become established.”

That reintroduction effort fizzled when the last of the released birds disappeared in the mid-1990s, leaving Mexico as the species’ sole home. If a fourth edition of Peterson’s venerable guide is produced, the Thick-billed Parrot is likely to migrate once again to the appendix, this time for good.

As regrettable as the Thick-billed Parrot’s disappearance in the United States may be, its status in Mexico is of much greater concern, for Mexico has always been the species’ stronghold. Unfortunately, it is highly endangered there as well, due to a combination of habitat destruction and capture for the pet trade. Moreover, given the peculiar ecology of the species and the history of land ownership in Mexico, saving this magnificent green-and-red parrot will not be easy.

Thick-billed Parrots are peculiar birds. Unlike most members of the parrot family, they shun warm, tropical forests in favor of high-elevation pine forests. Pines, in fact, are crucial to almost every aspect of their lives. Thick-bills feed almost exclusively on pinecones, and they prefer to nest in cavities in pine trees as well. A century ago, this degree of dietary and habitat specialization was not a bad strategy—the Sierra Madre Occidental was covered with millions of acres of old-growth pine forest— and the birds must have numbered in the tens of thousands (or more). But in recent decades, loggers have been hard at work in the Sierra Madre, stripping away the big pines. Today, the region remains largely forested, but that forest consists almost exclusively of young stands. Less than one percent of the old growth remains. The Thick-billed Parrot, in turn, has suffered a tremendous population decline. A survey in 1995 estimated that only 1,000 to 4,000 individuals remained in the wild.

Had Thick-billed Parrots been wholly dependent on old-growth forests, they would surely be extinct by now. In fact, the birds can forage successfully in younger stands, although those stands probably produce fewer pinecones per acre than the old growth. A more serious problem for the parrots may be the availability of nest sites in young forests. Thick-bills nest in tree cavities, especially those constructed (and abandoned) by woodpeckers. Older forests tend to have higher densities of woodpeckers, due to the greater availability of dead and dying wood and this, in turn, means more cavities for the parrots. Moreover, one prominent cavity-maker in the Sierra Madre Occidental, the Imperial Woodpecker, is now probably extinct, and its disappearance may have put a significant dent in the Thick-billed Parrot’s housing supply. A secondary problem for the parrots is the pet trade. Although not wildly popular with aviculturists, thick- bills are enough of a novelty to fuel an illegal trade in wild-caught birds.

Conservationists eager to save the Thick-billed Parrot must contend with two additional factors, one ecological and the other sociological. First, as noted earlier, some thick-bills migrate. They disappear from the northern Sierra Madre Occidental in the autumn and do not reappear until the spring. Where exactly they go during that time is a mystery, but winter flocks have been recorded in Durango, Sinaloa, Nayarit, and Jalisco, south and east to Colima and Michoacán. Without a clear understanding of their migratory behavior, conservationists cannot develop a comprehensive plan to protect the species. Second, in the wake of the Mexican Revolution, much of the land in Mexico was redistributed to the people in the form of communally owned ejidos. All of the members of an ejido must agree to any change in land management within its borders; thus, conservationists must work with every member of the community to effect any substantial change in practices.

Fortunately, the American Bird Conservancy (ABC) and the Mexican environmental organization ProNatura are willing to take on the challenge of protecting this wandering, charismatic parrot. The mountains around the Chihuahuan town of Madera are one of the few remaining strongholds for the Thick-billed Parrot. In this region, the parrots tend to nest very near to each other, resulting in loose aggregations of breeding pairs. A single old tree, riddled with woodpecker cavities, may harbor multiple nesting pairs of thick-bills. Moreover, in Madera the parrots will nest in old aspens as well as pines. ABC and ProNatura are trying to protect three key nesting areas. Two of the sites are owned by an ejido and will require patient negotiation to achieve permanent protection. In the meantime, the ejido has agreed to hold off logging the areas while negotiations (and field research) continue. The third site is privately owned, and ABC has raised the necessary funds to buy it.

Neither ABC nor ProNatura has focused on the surrounding forests, where the parrots forage for pinecones. They believe—with good reason, I think—that securing the breeding areas is the more urgent task. But down the road, they intend to make sure that the thick-bills have adequate foraging habitat. Nor do they know where the birds go when they leave the Madera area in the winter. Given the pace of technological advances in telemetry, it should soon be possible to fill this critical gap in our knowledge by capturing some of the birds, fitting them with satellite transmitters, and tracking them during their migration.

Last July, I was part of a small group of bird watchers who visited Madera in search of Thick-billed Parrots. Our guides were Sheri Williamson and Tom Wood of the Southeastern Arizona Bird Observatory. Boarding a van in Bisbee, Arizona, in the early morning, we wandered south through the dry hills of Sonora, then east into Chihuahua. By late afternoon, we had arrived in Madera. The next day, we left town at dawn and headed into the mountains, driving through miles and miles of pine forest, interspersed with small pastures and farm fields. I was struck by the fact that very few of the pine trees were especially tall or old, unmistakable evidence of the pervasive impact that logging

At a particularly fine patch of forest, Sheri and Tom stopped the van, and we piled out with our binoculars at the ready. The songs and calls of the birds brought back memories of my visits to southeastern Arizona, not too surprising, since we were only a couple hundred miles south of the border. I listened to the clear, whistled José María of a Greater Pewee, the soft yelping of an Elegant Trogon, and the silly peeps and chirps of a flock of Pygmy Nuthatches. Flocks of Mexican Chickadees, Bridled Titmice, and Olive Warblers flitted through the pines. Painted Redstarts chased insects in the oaks.

And then I heard the laughter. It was an odd thing to hear in the middle of the forest, reminding me of a distant band of revelers heading home after an all-night celebration—a raucous, happy sound. “Thick-billed Parrots!” Sheri shouted. We scanned in every direction, but the forest was too dense and the birds too far to permit a view. Later that day, Sheri and Tom took us to a patch of dead and dying aspens where the parrots gather each afternoon before heading off to roost. Dozens of emerald-green Thick-billed Parrots adorned the trees. They talked and squabbled, preened each other, climbed up and down the branches and, in general, brought a welcome touch of mayhem to the stolid forest. As the light began to fade and parrots headed off to roost, I thought about their precarious existence—the continued logging of the pine forests, the poachers, the mysterious migration they would undertake in a few months—and I wondered whether their laughter would still be heard 50 years from now.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library