Birding with Technology in the Year 2025: Our Predictions

By Peter Hart and Steve Kelling, with Jessie Barry, Brian Sullivan, and Chris Wood; Illustrations by Virginia Greene

January 9, 2020From the Winter 2020 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

At the dawn of the 2020s, a computer-science pioneer and an eBird inventor took a road trip through Silicon Valley to explore the future of birding—and see what new Birding Tech might be out within the next five years.

The first two decades of the 21st century were marked by rapidly advancing technology that radically changed people’s everyday experiences, including the birding experience.

That clunky, hard-copy field guide for bird identification is now a field guide app on your phone with an array of audio files, video clips, and photo galleries. Or, you can just ask your phone what that bird is—artificial intelligence has advanced to the point where the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Merlin app can identify bird photos for you.

Meanwhile, the guessing game of when birds on migration might arrive is a thing of the past. The Cornell Lab’s BirdCast project now scans the night skies via the nation’s Nexrad radar network and conjures up localized bird-migration forecasts via a magic mix of machine learning, cloud computing, and big-data analytics.

None of this was imaginable in the year 2010. Which got us to thinking…what unimaginable things are on the horizon as we roar into the 2020s?

To get a peek, we embarked on a road trip into Silicon Valley, where the future is being invented now, to ask tech innovators what birding might be like by the end of this decade. We talked to two dozen Silicon Valley insiders, including research and innovation executives at Google, IBM, and Facebook; three Stanford computer scientists; and the gaming pioneer who helped bring the world Candy Crush.

Spoiler alert—we quickly discovered that no one in Silicon Valley thinks they can see 10 years out. “Anything more than around five years, you’re just guessing,” they said. OK then, change of plans—what will birding be like by the year 2025?

The answers to that question already exist. Because as science fiction writer William Gibson once said: “The future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed.” In other words, any tech that will become widely adopted within five years has already been invented today. It just hasn’t hit the mainstream yet.

In our 24 interviews, we heard predictions that the smartphone is well on its way to becoming a miniaturized supercomputer. Moore’s Law (named after semiconductor pioneer and former Intel CEO Gordon Moore) states that tech devices with integrated circuits will continue to double in computing power every two years. While most heavy-duty computing is done via the cloud today, someday soon smartphones will be capable of high-performance computing all by themselves. We also heard loud and clear that social media and gaming will be even more dominant forces in how people interact, with each other and with organizations.

These and other tech drivers could reshape the birding experience for birders who use their smartphone. Sorry, we’re probably not headed into a Jetsons Age with personalized rocket packs for self-guided, high-elevation airborne birding within the next five years. But your smart binoculars may have a digital readout that IDs a bird for you. Your smart bird feeder might upload its own bird checklist. Your eBird checklists could feed a real-time conservation-monitoring algorithm that dims the lights in big cities—and saves more migrating birds.

By the Year 2025, Birding Could be the Latest Addictive Gaming Craze

Gaming has gone way beyond Playstation and Xbox. Anybody with the Starbucks app could now be a gamer who races out over a lunch break to chase stars that add up to real-world discounts on lattes. The world of gaming is creeping into our everyday lives, and gaming motivations are driving social behavior. What if gaming came to birding?

In the future, there could be gaming rewards for the digital birder, too. Whereas today there are Top 100 eBird leaderboards for every state, the eBird motivations of the 2020s could be more personalized.

Games to Make You a Better Birder

Many foreign-language learning apps such as Duolingo already offer incentives and status symbols as encouragements to advance to higher levels. What if eBird offered rewards for skills and accomplishments—a badge for a lifer bird, or an encouraging note for the first seasonal sighting of a migratory species? (“Way to go, that’s your first Yellow-rumped Warbler this spring!”) FitBit tells users when to get up and move around to meet their goals for steps. What if eBird gave you a gentle nudge to go on a birding streak and upload checklists 10 days in a row?

Perhaps eBirders could even personalize the goals they want to achieve, from mission-oriented conservation birding (targeting IUCN Red List vulnerable birds) to more esoteric pursuits, such as birding for phylogenetic diversity (looking for a Wrentit along the West Coast, the only member of its family in the entire Western Hemisphere). More refined metrics for rewarding a birder’s proficiency and effort could encourage masses of birders to up their birding game and upload more data.

Games to Organize Competitive Birding

How about a friendly game of birding? Fantasy football uses tech to bring friends together in computer-generated leagues that score data based on real-world results. With a little co-opting of gamesmanship from the world of fantasy sports, merged into the digital mechanisms for recording and tracking bird counts, the tech could be developed that would enable birders to compete in leagues organized online—but based on the birds that players actually see outdoors. (An early, single-player version of fantasy birding already exists.)

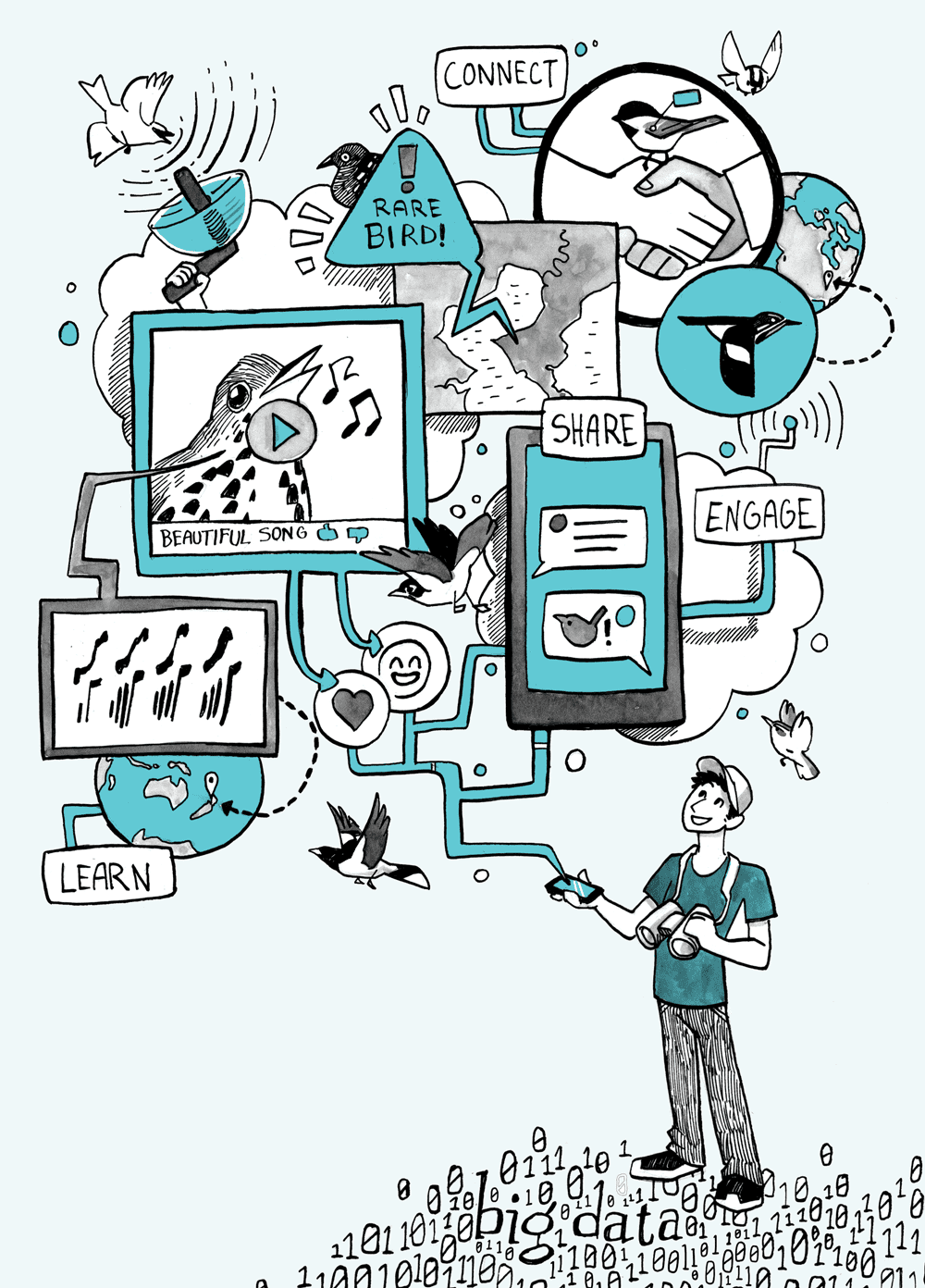

By the year 2025, birding could become a social-media movement

Tech diffusion is a term for the global spread of technology. Smartphones have spread far and wide and are the primary, and often only, way for people to access the internet in much of Asia, Africa, and India. And many apps can be customized for local languages and dialects. The eBird mobile app is now available in 27 languages, and Merlin covers more than 100 countries around the world.

At the same time, nearly half of the world’s 7-billion-plus people are on social media—with more than 2 billion users on Facebook, and more than a billion each on YouTube, Instagram, and WhatsApp.

Imagine a world where the global force of social media and the burgeoning network of eBird and Merlin users are integrated. It’s a world where Birding Tech connects birders in a social media–sharing experience, and where scientists can connect with birders to make special requests for the data they need.

eBird Becomes a Sharing App

The eBird checklist of the future could be a lot more than one person’s bird sightings. What if you had the choice to make eBird a virtual venue for sharing successes and aspirations with fellow birders, cheering others on and comparing notes for tomorrow’s birding adventures? Birders could coordinate in real time in the field, sharing rare bird alerts when and where birders can make immediate use of them.

A social media–enabled eBird could facilitate team birding, in which birders band together (in effort, if not physically) to broadly cover an area and record their own birding blitzes. Global Big Day (which recruited nearly 20,000 birders in a single, global birding effort last October) could be every day…birders working together, encouraging and sharing experiences.

eBird Offers a Most-Wanted List for Scientific Research

The beauty of eBird is that it works for birders and scientists alike—a handy digital checklisting tool for the former, a big-data treasury about birds for the latter. But what if eBird made it possible for scientists to make special requests, soliciting more information about rare sightings or species that are the subjects of in-progress research? What if eBird could talk back to users?

If an eBird checklist contained a species of particular research interest, perhaps the eBird app could solicit the user to tell scientists more. (What was your bird doing? What did the surrounding habitat look like?) Or upon opening up their eBird app in the morning, users could be greeted with a list of “GoFindMe” birds—a most-wanted list of species needed to support current scientific studies. With such a mechanism, researchers and wildlife agencies could direct birding effort toward the needs of science and conservation.

By the year 2025, AR* and AI** will combine for a more powerful birding experience

*augmented reality **artificial intelligence

Augmented reality is different from virtual reality. VR is the Oculus goggles that transport you to an alternate, digital world (like a zombie-infested wasteland in a VR video game). AR is Google Glass—you still see the actual world around you, but your view is augmented with data readouts and digital displays.

Google Glass didn’t catch fire in its first iteration, but it didn’t go away. The tech just needs a bit more time to mature (and the glasses need to be a bit less goofy). Silicon Valley is hard at work on developing AR that adds helpful information displays to your view of the real world, fueled by artificial intelligence technology that can interpret what you’re seeing. Consider the Google Translate app’s viewfinder, which can morph the image of a Spanish-language restaurant menu into English. Now imagine how AR could be applied to a birder’s-eye view.

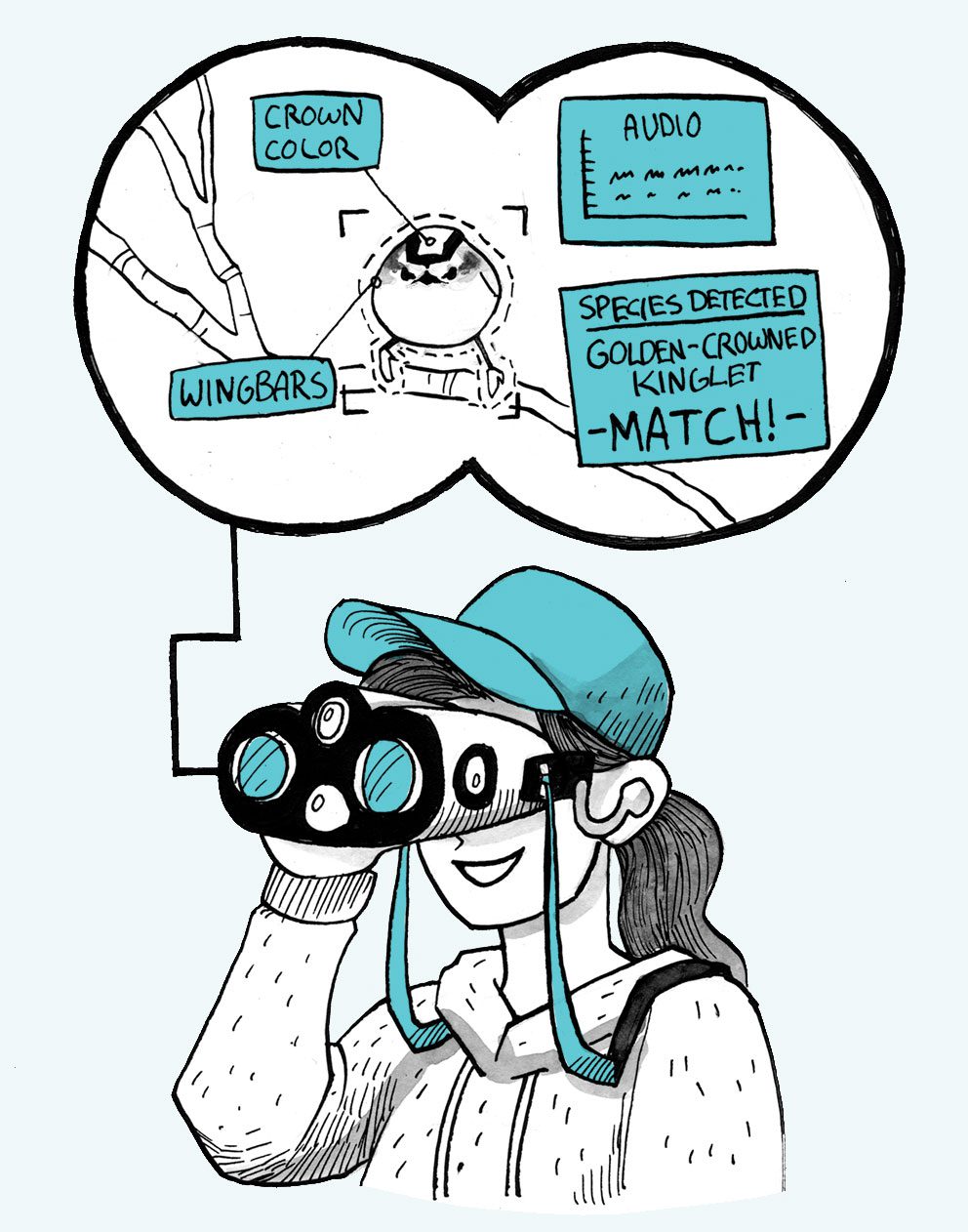

Smart Binoculars That Suggest a Bird ID

Optics with AI-powered bird ID via a smartphone connection are coming soon (see more about the Swarovski’s Digital Guide in sidebar). As a next step, this tech could be infused directly into binoculars. Imagine locating a bird in your binos, and then seeing a list of species names pop up beside your bird in the viewfinder based on the bird’s size, shape, color, and recent eBird sightings in the area.

AI-Powered Apps That Transform Your Smartphone Into a Birding Coach

With artificial intelligence tied to a user’s life list and GPS coordinates on their eBird app, a smartphone could soon be a handheld birding guru. Heading out to bird the fall migration on a mid-autumn morning? Your smartphone could send you a push notification with a primer for IDing confusing fall warblers, customized for species seen recently near you on eBird. Or better yet, you may be able to slip your smartphone into “bird guide” mode—imagine if Merlin could act like Amazon’s Alexa and autonomously listen for and interpret ambient sounds, picking up bird calls and telling the user what species the app is hearing.

For vacationing birders, the Merlin app can already generate a list of the bird species that you’re mostly likely to see after you step off the plane. In the future, Merlin might go a step further by offering you customized species ID tutorials, audio birdsong quizzes, and recommendations on where to go to find new life-list birds in your vacation spot.

AI-powered Birding Tech for the smartphone could also lessen the learning curve for beginning birders. Traditionally, getting started in birding meant finding a mentor to teach the keys of bird ID. But a merger of AI and online education could pull that mentoring process into an app that uses tech to make new birders successful on their own, without the constraints of finding a more experienced birder or hiring a guide.

By the year 2025, smart devices could identify birds on their own

And not just identify birds, but upload their own bird checklists—and provide complete environmental reporting on air quality, climate tracking, and more.

Birds are widely touted as indicator species, barometers of the health of our environment. If loons are seen on a lake, the water is presumably clean and prey fish populations are likely to be healthy.

Birders, then, act as an environmental monitoring network by reporting checklists on the presence and absence of birds—data that can tell scientists something about the environmental conditions in the places where the birds were seen.

Another popular axiom in Silicon Valley is Metcalfe’s Law, named after Robert Metcalfe, a visionary computer engineer who was one of the pioneers of creating the internet in the 1970s. Metcalfe posited that the value of a network increases with the square of its participants. With more than 500,000 eBird users spread across every nation in the world, the eBird data-reporting network is primed to become the biggest, and therefore most valuable, environmental monitoring network (if it isn’t already).

At the same time, technologies are rapidly advancing in other areas of environmental monitoring—particularly in shrinking the monitoring tech. Air-quality monitoring devices that can measure particulates down to 2.5 micrometers in diameter (small enough to be viewable only by an electron microscope) are now available in handheld models. Cornell University experiments with ChipSat technology are going even smaller, using thumbnail-sized sensor chips embedded in collars fitted around the necks of cows to measure air quality in dairy barns on upstate New York farms.

The same kinds of innovations in hardware technology connected to the eBird network could launch another era of rapid expansion for eBird deployment, with smart devices monitoring birds autonomously via artificial intelligence—and ChipSat-like sensors enabling an all-in-one environmental monitoring device that captures data on birds, air, climate, and more.

Smart Bird Feeders Could Turn the Backyard Feeder Into a Data-Monitoring Station

Smart refrigerators can look inside your fridge, see what ingredients you have for dinner, and recommend a recipe. Smart weather stations are now tracking rainfall, UV levels, air pressure, humidity, wind speeds, and even generating hyper-localized weather forecasts out of a single home’s backyard.

Are we that far away from the era of the “smart bird feeder”?

The following technologies already exist: remote digital cameras that autonomously capture photos, continuous audio-recording devices that capture almost every sound within several hundred meters, and AI software that can autonomously identify and categorize visual and audio data.

Put all that tech into a backyard feeder, and the smart bird feeder of the future might be able to tell you which bird species ate your bird seed today, and which nocturnal migratory birds were heard flying over your house last night.

Connect that smart bird feeder to your home’s Wi-Fi network, and your feeder full of sunflower seeds is now empowered to upload its own eBird checklists—or text you an alert when a new species shows up.

Integrate the other tech that’s already in today’s smart backyard weather stations, and the data flow from a smart bird feeder could go beyond reporting on birds to include air quality (monitoring smog or wildfire smoke) and climate tracking.

Robo-Birders Could Roll Out To Autonomously Survey Birds Across The Entire World

The same smart bird-feeder tech of the future could be deployed into a drone or other mobile device.

Such a machine (call it a “robo-birder”) could detect (visually or via audio) more species than ever possible by humans conducting bird surveys. It could gather other ambient environmental data as well, such as air quality or climate data. And it could go anywhere—into the most remote or least hospitable places on Earth.

The Australian bush country, the African Sahara—many of the world’s least-birded areas could be within the reach of a roving robo-birder that could upload data into the eBird network.

By the year 2025, birding could be a force for rapid-response data reporting and real-time conservation

So far we’ve discussed the possibilities for technology to improve the experience for birders and optimize the data flow for scientists engaged in conservation.

But what if tech could directly benefit birds by speeding up the decision-making process in conservation?

“Governments do not work at Moore’s Law’s speed,” said one of the Silicon Valley sages we interviewed. But technology does.

Advances in the real-time aggregation and analysis of big data about bird sightings—and the delivery of that data stream directly to authorities with the power to make conservation decisions–could fast-track the process from seeing birds to saving birds.

Birder-Powered Reporting Could Dim the Lights in Big Cities on a Big Migration Night

Building operators in Houston and Pittsburgh are already monitoring BirdCast forecasts for evenings of heavy overall bird migration, when lights should be dimmed to reduce building collision risks. The next step is to refine that bird migration-data reporting further, perhaps using eBird-powered algorithms to detect when smaller but significant flocks of particular species are passing through an urban area—such as the sparrows, warblers, and thrushes that are most susceptible to building strikes. This collision risk–mitigation model could also be applied in other areas, such as powering down wind turbines on high-migration nights.

The Future of Birding Tech Depends on Birders and Data

Will any of these Birding Tech possibilities become reality by 2025…or ever? Only time will tell. But the predictions we offer largely depend not on Silicon Valley, but on birders.

Specifically, they depend on the data that birders are willing to share. It took millions of eBird checklists to empower the AI tech that enables Merlin to identify a bird anywhere in the United States. It will take many millions more citizen-science contributions to keep advancing birding technology.

We presented you with some possibilities for the Birding Tech of the future. You, the birder, can help make that future a reality.

About the Authors:

Peter Hart, a Silicon Valley artificial intelligence and robotics pioneer, serves on the boards of the Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Steve Kelling has led the development of eBird since its inception and is codirector of Avian Population Studies at the Cornell Lab.

Cornell Lab project leaders Jessie Barry (Merlin), Brian Sullivan (Birds of the World), and Chris Wood (eBird) have been involved in developing eBird and associated applications since the early 2000s.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library