Battling a Green Glacier: How a Native Tree Became a Threat to Nebraska’s Grasslands

Is there such a thing as too many trees? In Nebraska—home of Arbor Day—ranchers are battling the inexorable march of redcedar trees across Sandhills grasslands that sustain both livestock and birdlife.

September 27, 2023

From the Autumn 2023 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Sarah Sortum has a photo of her grandparents receiving a conservation award in 1973 for planting trees across their ranch in the eastern Nebraska Sandhills.

“In my grandparents’ generation they were really encouraged by conservation programs to plant trees,” says Sortum, who now helps run that same family-owned acreage, known as the Switzer Ranch. “Remember, this is the Arbor Day state. That’s a way of life in Nebraska, planting trees.”

The trees, primarily native eastern redcedar, offer shade and visual relief from the unrelenting horizon of prairie. Their dense branches and evergreen needles provide a windbreak and natural snow fence to protect the homestead, and a virtual “outdoor barn,” in Sortum’s words, for calves in spring.

“Now we have these beautiful, mature cedar windbreaks, and they are valuable to us,” she says. “But now we have all this seed source.”

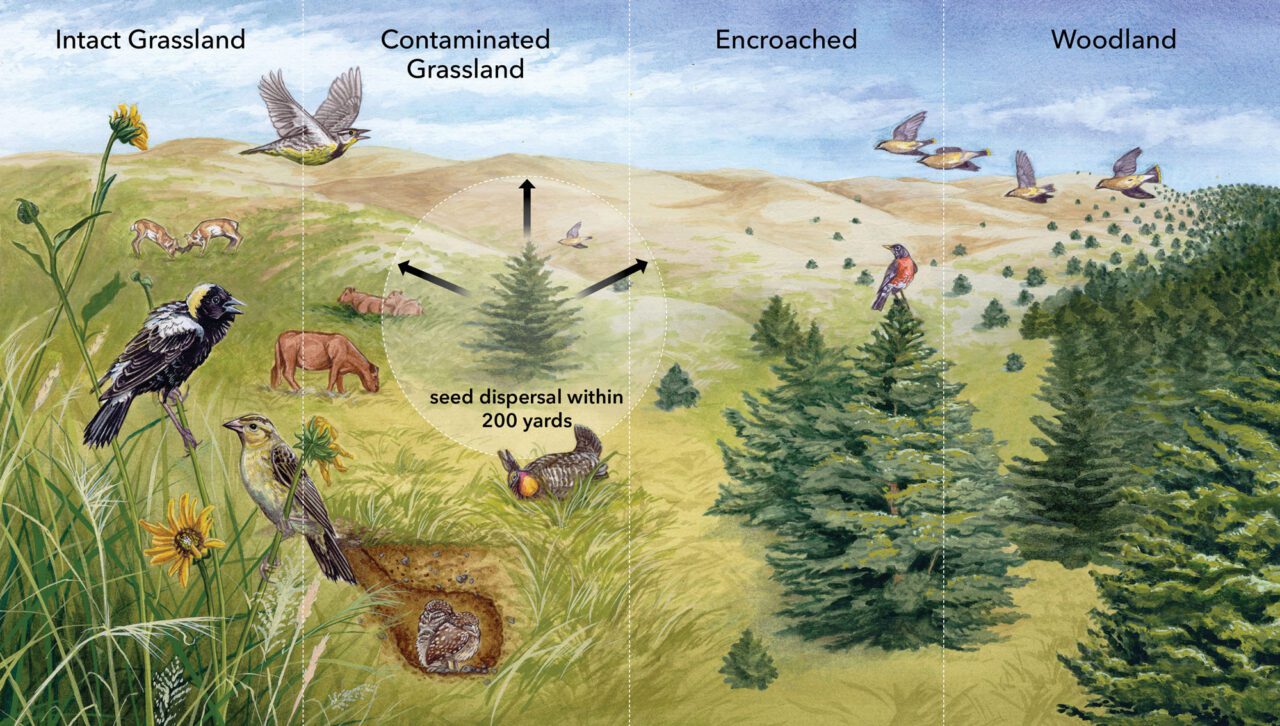

Research from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln shows that that seed source—the fully grown redcedars bursting with tiny cones at the ends of their evergreen branches—can propagate a wave of cedar seedlings that spread out a couple hundred yards away from the parent tree. Two generations after her grandparents planted them, those redcedars are spreading out from the homestead and windbreaks, creating an ungovernable front of woodland. And it’s not just the Switzer Ranch. The same thing is happening throughout the Sandhills—and across much of the central Great Plains.

The advancing wall of conifers, dubbed “the green glacier” by Oklahoma State University rangeland ecologist David Engle, threatens the very existence of grasslands—and grassland birdlife. According to Engle, the woody encroachment, as ecologists call it, “is changing endemic avifauna to an extent equivalent to that of the Pleistocene glaciation.”

In Nebraska’s Sandhills, the transformation is scaring the bejeezus out of ranchers, bird biologists, and everybody concerned that the conversion of grassland to woodland will eat up habitat for prairie wildlife, and doom the ranching way of life. Says Sortum, “The biggest common challenge we’ve got is the redcedar.”

The solution—or at least the resolution that ranchers and conservationists are aiming for—is a joint effort to use mechanical tree removal and prescribed fire to beat back the advance of trees and preserve land for cattle and prairie wildlife.

“We really see it as the biggest threat to the Sandhills ecosystem,” says Shelly Kelly, executive director of the Sandhills Task Force, a rancher-led organization that’s leading the fight against redcedar on private lands.

And in Nebraska, almost all land is private land. Without the help of landowners, Kelly says, nothing much will be able to protect ranching, the prairie, or grassland birds from the trees.

“Hard-pressed to find a single tree”

The Sandhills occupy roughly 20,000 square miles in north-central Nebraska, a quarter of the state. Formed as shifting, growing dunes of wind-driven sand, the hills stabilized as recently as 1,000 years ago and today are capped by mixed-grass prairie. Known by locals and ecologists as “choppy sands,” the low but steep hills are prone to slumping areas called “catsteps” and wind-caused “blowouts” of exposed sand.

The Sandhills border on arid—23 inches of annual precipitation in the east fading to 17 inches in the west, dry enough that the landscape teeters between prairie and woodland. Yet beneath all that sand and dry-prairie grasses lies the prodigious Ogallala Aquifer, one of the world’s largest stores of groundwater and source of about 30% of agricultural irrigation in the United States. And as a grassy biome, the vast Sandhills are globally significant—one of the largest remaining intact temperate grasslands in the world, according to Melissa Panella, manager of the Wildlife Diversity Program for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. According to the Commission’s state wildlife action plan, the Sandhills are a hotbed for the so-called Tier I at-risk Species of Greatest Conservation Need, including Baird’s Sparrow, Burrowing Owl, Ferruginous Hawk, Loggerhead Shrike, Short-eared Owl, Sprague’s Pipit, Whooping Crane, and Long-billed Curlew. In fact, the western Sandhills is one of the “last primary strongholds” of curlew, says Joel Jorgensen, nongame bird program manager for the Game and Parks Commission.

When European explorers first surveyed the land, hardly a tree could be found. “You could travel across the entire Sandhills without seeing a tree,” says Dillon Fogarty, researcher and program coordinator for working lands conservation at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. “They were tucked in on just a few stream banks.”

In those days, the force on the landscape keeping trees in check was fire—some set naturally by lightning, but most by busy humans with an eye toward game and land management. The earliest inhabitants of the Plains, says Fogarty, “actively shaped their environment to create an environment that they could thrive in.

“Indigenous groups have been using fire and shaping ecosystems for thousands of years. And our wildlife species in the Plains evolved with systems that burn frequently.”

As settlers and their government forced tribes such as the Pawnee, Lakota, and Plains Apache from the Sandhills, they also removed the aggressive use of fire to manage the landscape. In fact, the newcomers tried to prevent any fire at all. Under this new regime, the scrappy but fire-vulnerable eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) was able to venture out from the steep slopes and canyon walls along prairie streams and onto grasslands, where its attractive powder-blue seed berries were consumed and expelled by the likes of Cedar Waxwings and Yellow-rumped Warblers. Redcedars aren’t a fast-spreading invasive species in their own right; some 95% of a cedar’s seed production in a year falls within just 200 yards of the seed source, according to Fogarty’s research. But without fire to burn off their advances, the trees emerged from their refugia and spread across the prairie.

And that’s not all. Settlers unwittingly aided the destruction of the prairie by planting more trees—even making an organized effort of it. In the 19th century, J. Sterling Morton, a newspaper editor in Nebraska City and later secretary of the Nebraska Territory, enthusiastically promoted tree planting. After statehood, he proposed a holiday to encourage citizens to plant trees. On the first American Arbor Day on April 10, 1872, enthusiasts planted a million trees in Nebraska that day alone. For decades, civic organizations and government agencies continued to plant trees and promote tree planting.

It wasn’t a hard sell. The newcomers to the prairie (many settlers with European heritage were woodland people by ancestry) found comfort and practical uses for a few trees, from firewood to fence posts. As those trees have matured and produced seed, that 200-yard expansion radius of seeds and seedlings steadily expanded, generation by generation.

“So we have a significant part of the Plains now that is covered by trees and their seed dispersal,” Fogarty says.

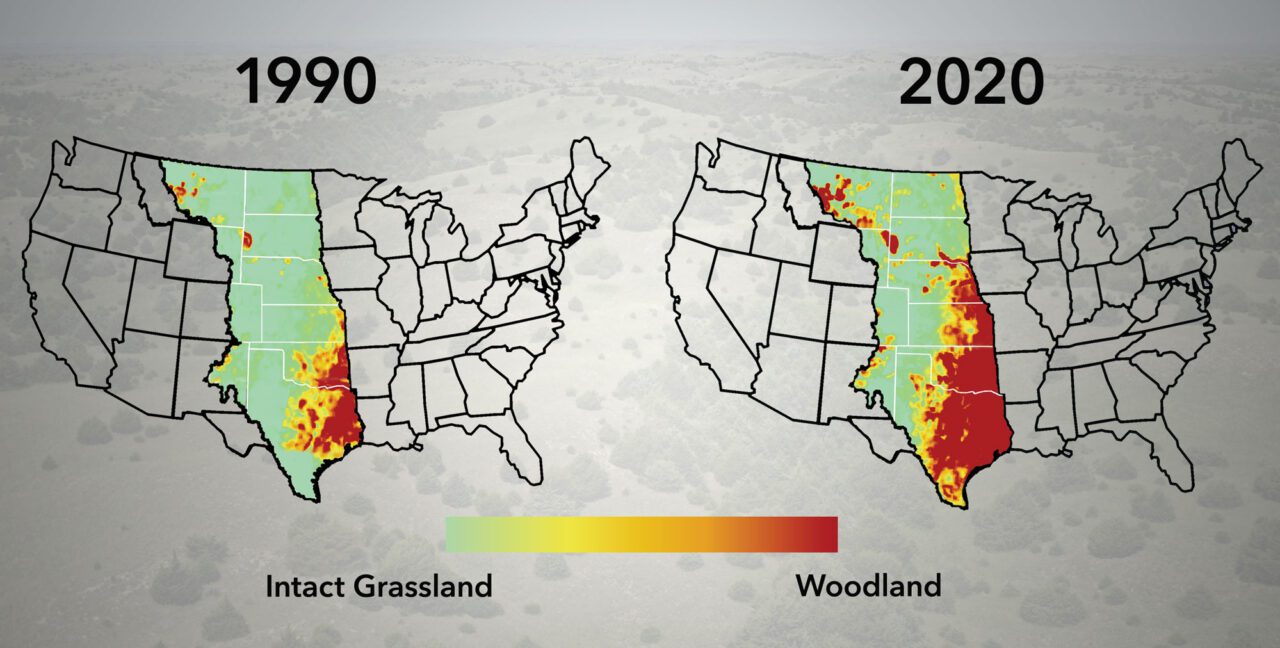

And that means the trees are on the move. According to 2022 research published in the Journal of Applied Ecology, tree cover has increased 50% across the rangelands of the western U.S. in the last 30 years. The creeping woodlands threaten open prairie, prairie wildlife species, and the ranching industry. They also increase the chances of uncontrollable wildfire.

In Nebraska specifically, nearly 8 million acres of intact grasslands are estimated to be at risk from woody encroachment, according to the Nebraska Great Plains Grassland Initiative of the federal Natural Resources Conservation Service.

“We’re losing the battle,” says Fogarty.“ As long as we’re having the trend of woody encroachment that’s continuing to increase…long term that means we’re not able to sustain our grasslands.”

“That’s sacrilegious in Nebraska”

Sarah Sortum’s great-grandfather and his brother first came to the Sandhills in the early 1900s as market hunters, shooting prairie-chickens and Sharp-tailed Grouse to ship by rail to restaurants in Omaha. The brothers decided to stay and homesteaded on adjoining sections of land.

“And we’ve been here ever since,” says Sortum. She grew up on the ranch, left awhile with her husband to manage a high-end guest ranch in Colorado, and then returned to join her older brother in the Sandhills.

Today the Switzer Ranch grazes beef cattle and operates a ranch-based tourism business called Calamus Outfitters. Coyotes, badgers, porcupines, bobcats, and both mule deer and whitetails roam the property. Sortum also frequently sees the classic birds of Great Plains grasslands: Grasshopper Sparrows, Bobolinks, Eastern and Western Meadowlarks, and various sandpipers and herons. Greater Prairie-Chickens and Sharp-tailed Grouse, descendants of the birds hunted by her great-grandfather, continue to occupy the ranch. The chickens stick to the low meadows and benches at the base of hills. The sharptails seek out the sparser grass, plum thickets, and patches of leadplant on the “big, choppy hills.” Sandhill Cranes sometimes fly over on migration, though they rarely land. Says Sortum, “That’s kind of how we mark our spring and fall.”

Two birds common now, but that Sortum rarely saw growing up, are Blue Jays and Northern Cardinals. Both species eat redcedar berries and thrive in the advancing woodlands. She says that 20 years ago, when a bunch of little trees started popping out of the pasture on her family’s ranch, “nobody really thought too much of it.”

“Nobody really got excited. And nobody went to cut them, because that’s sacrilegious in Nebraska,” says Sortum. “And so it got away from everybody. … All of a sudden you wake up one day and go, ‘Oh my goodness, this is starting to cut into my bottom line because look at how much grass I’ve lost.’”

Sortum wasn’t the only one caught by surprise.

“One of the things that has been a killer in the Sandhills and other parts of the Plains is a disbelief that woody encroachment can happen,” says Fogarty. “People in the conservation community and otherwise have long thought that the Sandhills is too dry, too sandy for encroachment, that it just couldn’t happen in that landscape.”

But that’s not true, he says: “Even in the western Sandhills, if we have a seed source, we have spread.”

“Bottom line is that we’re a prairie state”

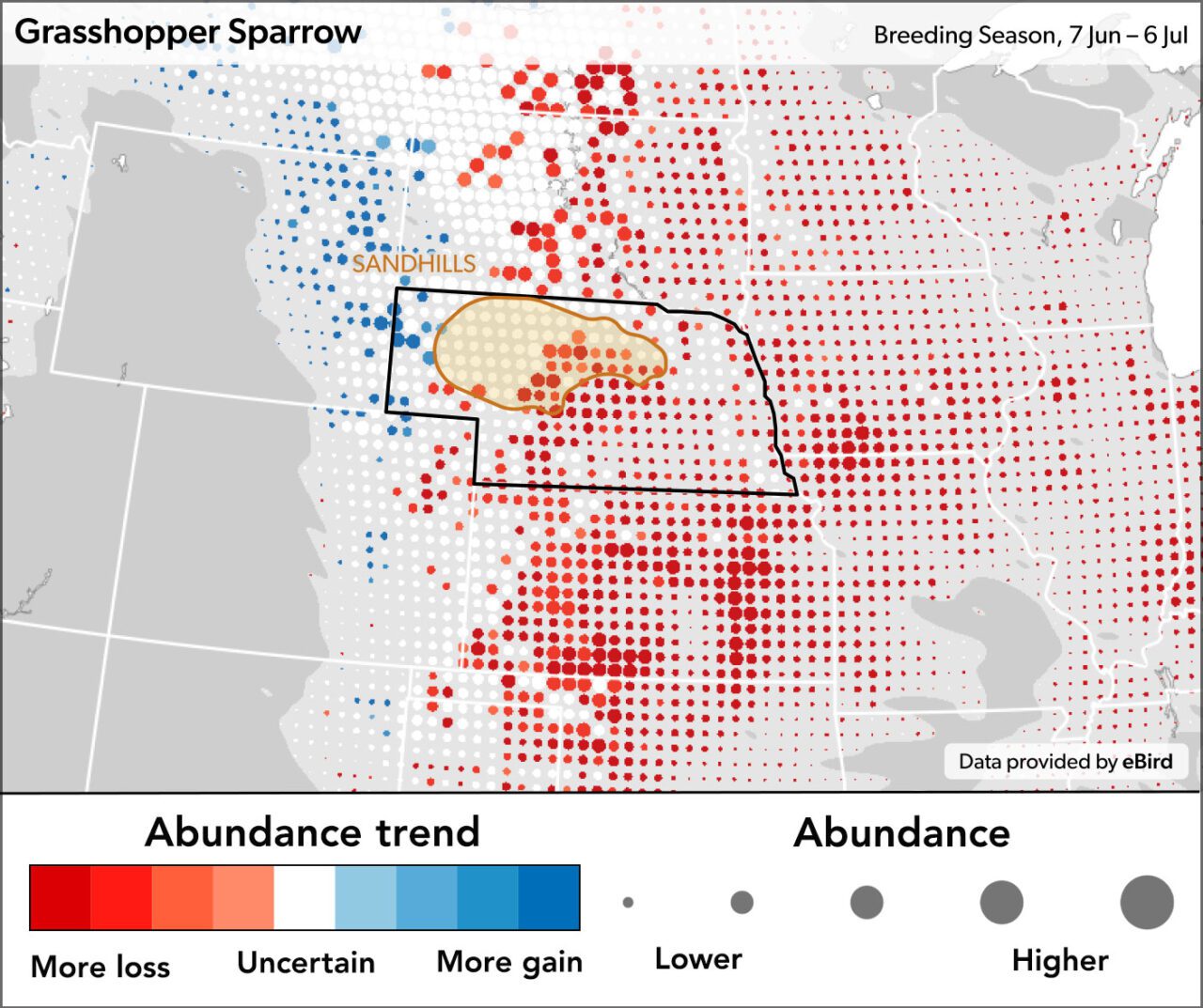

The loss of open prairie threatens a host of grassland birds, and the appearance of just a few trees per acre is enough to cause some bird species to disappear. According to various studies in the Sandhills and nearby grasslands, Grasshopper Sparrows are most abundant when the redcedar canopy is less than 10% by area, and they disappear entirely when woodlands cover a third of the area.

Across the continent, grassland birds are in crisis. In the landmark 2019 study published in Science that showed North America had lost 3 billion birds since 1970, grassland birds were by far the biggest losers—with a total population decline exceeding 50%.

According to Joel Jorgensen, the nongame bird program manager for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, the Sandhills and surrounding area are the best place to take a stand and spark a turnaround for grassland bird populations.

“I think the bottom line for me is we are a prairie state,” says Jorgensen. “If we’re going to conserve most of our grassland birds, this is the area, the Great Plains, where we need to focus that attention.”

But the loss of birds isn’t the only, or even the most important, concern of people living in the Sandhills. According to that 2022 study in the Journal of Applied Ecology, the 50% expansion of tree cover across U.S. rangelands—eating up an area of grasslands nearly the size of South Carolina—has cost livestock producers between $4 billion and $5 billion due to the loss of grass and forbs for forage.

If we’re going to conserve most of our grassland birds, this is the area, the Great Plains, where we need to focus that attention.

Joel Jorgensen, nongame bird program manager for the Game and Parks Commission

One of the authors of that study—Dirac Twidwell, a rangeland and fire ecologist at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln—says there are many other costs to people living in this region, too. For example, he points out how redcedar woodlands shelter animals such as white-tailed deer, turkeys, and coyotes that act as reservoirs and transporters of ticks, especially the lone star tick—a vector for several serious diseases that afflict humans.

And ironically, Twidwell says the absence of fire in Nebraska’s Sandhills can increase the risk of severe wildfires that endanger people and property, as woody tinder builds up on a marginally arid landscape.

The threats from redcedar are also creeping into state education funding. The Nebraska Board of Educational Lands and Funds, the largest landowner in the state, leases much of its acreage as rangelands for livestock grazing as a source for tens of millions of dollars every year that go into the general school fund.

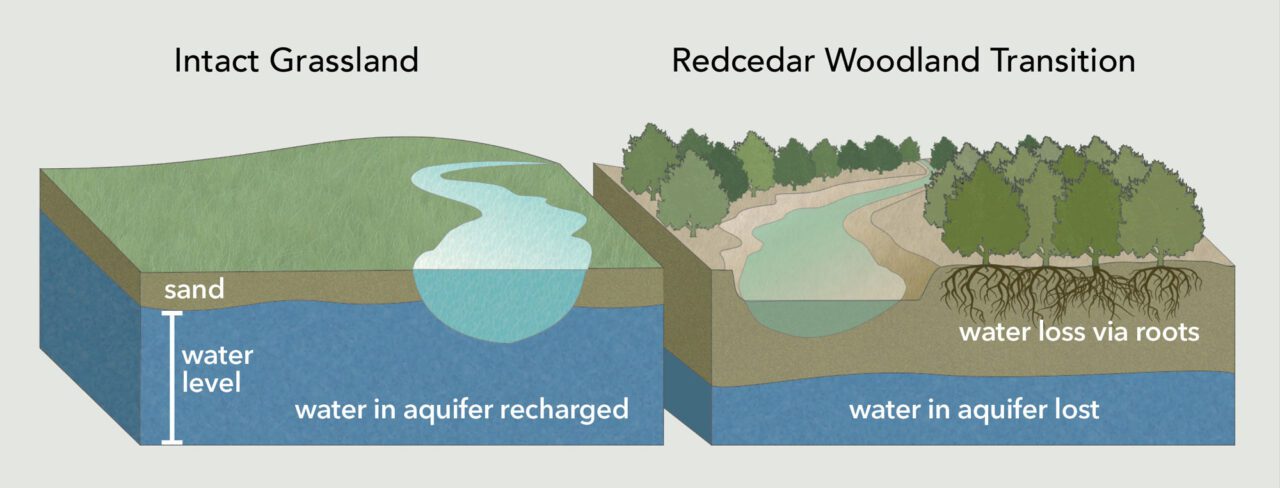

The redcedars even threaten the bountiful Ogallala Aquifer. Forests are thirstier than grasslands, sucking up surface and shallow groundwater.

“This affects every citizen that lives in the Great Plains,” says Twidwell.

The loss of forage and profitability from woody encroachment, he says, has a pernicious effect that accelerates the problem. Ranching survives on rather thin profit margins, and when profits decline, the circumstances are ripe for ranchlands to be converted into other land uses, such as row-crop agriculture or development. The overall effect is the loss of grass, the loss of grazing, and the loss of a vanishing prairie ecosystem with vulnerable wildlife communities.

Says Twidwell, “What we’re seeing is entire ecosystem collapse, [with] surprising consequences in ways nobody would expect.”

“No way to get on top of it”

Once Sarah Sortum and her family realized redcedar was claiming their range, they attacked with chainsaws, handsaws, loppers, and even a skid-steer in an attempt to destroy the invading trees.

“There was absolutely no way we could get on top of it, and it was also quite expensive,” she says. “That’s why we turned to prescribed fire, which was really hard for my dad, because, culturally, he grew up where fire was very scary and bad.”

At the outset, Sortum says her family was on their own with undertaking prescribed burns. They didn’t know where to turn for advice and support, except the rural volunteer fire department—and even they didn’t want to help at first.

“We asked if they would come out and help, and almost everybody on the fire department did not want us to do our fire,” says Sortum.

“But they came out and helped anyway,” she says. “They weren’t really in favor of it, but they’re good neighbors.”

Soon after those first burns were completed, the neighbors around the Switzer Ranch property took notice of what grew back in the blackened, charred pastures—thick grass and wildflowers, without trees.

“It didn’t take long for our neighbors to look over the fence to see what it looked like, and they go, ‘Oooh, that looks pretty good!’” Sortum says. “They asked us if we would help them burn.”

Her family has continued to burn several hundred acres every spring, so that any given acre gets fire every 10 to 12 years. Sortum says she’s impressed by the benefits to resident birds.

“Especially those first two years after a fire, there’ll be a few more forbs that come up than normal … the flowering plants that draw in the bugs,” Sortum says. “When I go to those areas, I swear those prairie-chickens and the grouse, they march their broods into those areas in late July and early August, and that’s where they raise those chicks.”

Related Stories

Greg Gehl is another Nebraska rancher who, like Sortum, was stunned to discover that redcedar was poised to overtake his grazing lands in the eastern Sandhills.

“We realized all of a sudden, we’re losing grass!” Gehl says. “Taxes don’t go down. Fixed costs don’t go down. So where do we have to make that back up? We’ve got to get rid of the cedars!”

As Gehl became more concerned, he got in touch with Ryan Lodge, the Sandhills working lands coordinator for Pheasants Forever, a nonprofit conservation group that works for the protection and rehabilitation of grassland habitat for prairie game birds. Though employed by Pheasants Forever, Lodge works in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service office in the town of Neligh, where he helps landowners connect with various grant-supported and government cost-share programs, such as conservation incentive programs funded through the federal Farm Bill. Lodge helped Gehl develop a plan to beat back the trees and open up his grassland.

“What it amounts to is you get a more holistic approach to management,” says Gehl. “So when cows do good, wildlife does good.”

Gehl began by shredding and cutting and piling trees. Then he introduced prescribed fire to the ranch.

“Originally we had a fire department that was dead set against burns,” he says. But redcedar changed a lot of attitudes. “Over a 10-year period, we went from a fire district with two stations that didn’t own a torch, wouldn’t do a burn. We now own six torches and do multiple burns a year.”

These days, Gehl is promoting fire as a necessary and constant tool for managing rangelands.

“We are going to have to burn every year,” he says. “That’s just a fact of life now. That’s the most economical control. It’s amazing: People who were dead set against it, they have evolved into helping.”

According to Gehl, prescribed fire offers ranchers a way forward through the thicket of woody encroachment, whether their chief concern is for birds or ranching.

“As the birds leave, so does the grazing,” says Gehl. “For me the birds and the wildlife are secondary, staying alive is primary. But if we can provide a total, healthy ecosystem, then everybody is happy. Everybody should be able to survive on that.”

And there’s evidence that the burns are working. In the Loess Canyons—a different prairie landform of bluffs, ridges, and steep gullies just south of the Sandhills—landowners have been battling trees for two decades. According to Fogarty’s research at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, as fire killed redcedars and reduced the extent of woodlands, grassland bird species diversity increased across 65% of the Loess Canyons—and some bird populations are rebounding dramatically (Northern Bobwhite are up 200%).

“Grassland birds are responding,” says Fogarty. “It’s pretty impressive what they’re doing there.”

“What’s good for the ranch is good for the wildlife”

According to Ryan Lodge at Pheasants Forever, the changing tide of bringing ranchers on board to fight cedars is the key to keeping grassland habitats on the ground in Nebraska.

“Nothing happens without landowner buy-in,” Lodge says. “I mean, Nebraska is 97% privately owned. We can have all the money and all the programs in the world, but if we don’t have landowner buy-in, we don’t do anything. They are our biggest partner. They make this happen.”

To foster more of those types of partnerships, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission has a team of more than 20 employees working with ranchers to fund habitat work, primarily redcedar removal, through a combination of state and federal money (much of it coming through the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act, which is funded through taxes on the sale of firearms). The Game and Parks Commission works with various partners including The Nature Conservancy, Northern Prairie Land Trust, and the Santee Sioux Nation. But most of the tree removal and grassland restoration occurs on private land, says commission wildlife biologist T. J. Walker.

“Ultimately the landowners are going to be the ones who are going to win this battle,” says Walker. “We’re trying to help them get ahead of it, but they are the ones who are going to have to maintain it and keep on top of it down the road.”

Alongside the Game and Parks Commission, the Sandhills Task Force—a rancher-led group—is securing grants for cost-share programs, providing technical advice, and helping ranchers find reliable contractors for removing and controlling the spread of trees. According to Shelly Kelly, the task force director, it all starts with changing entrenched attitudes about fire.

“A lot of the ranchers believe that fire is a four-letter F-word in the Sandhills, and that we should not have any fire, so we work really hard on that fire side to educate people about prescribed burning,” Kelly says. “That it’s very different from wildfire, and that in some areas it’s really the best answer for controlling this.”

The task force teams up with The Nature Conservancy to develop prescribed burn plans and train landowners in using fire. A wildlife biologist is involved in developing each burning plan to make sure “all of our projects have a wildlife focus,” says Kelly.

“We are blessed to live in an area where what’s good for the ranch is good for the wildlife,” she says. “The prairie-chickens and the grassland birds need open and intact grasslands. The same way with the cows.”

And according to Kelly, the fate of the prairie depends on that relationship between ranchers and grasslands: “If we lose our land stewards, we’re going to lose the stewardship that goes along with them.”

Sortum agrees. If ranchers don’t succeed in preserving the prairie, she doesn’t know who will step up. Battling redcedar has become “part of how we do business now.” Without the vested interest of ranchers in keeping the grasslands open, no other group will be willing or able to spend the money needed to fight a constant battle with trees.

“That’s my real big concern. If the land use changes and it doesn’t make sense for people to stay on top of the problem, they’re going to let it go and it’s going to turn into a forest instead of a grassland,” she says. “It’s in our best interest to keep it a grassland.”

About the Author

Freelance writer Greg Breining is a frequent contributor to Living Bird. He writes about wildlife, the environment, health, and science.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library