A Sense of History, a Question of Conservation

By David S. Wilcove

From the Summer 2014 issue of Living Bird magazine.

July 15, 2014

With conservation dollars more scarce than ever, how do we decide which species to save?

As the actress Gloria Swanson once observed, “Life is 95 percent anticipation.” I would quibble with her arithmetic, but there is no doubt that planning for a trip can be almost as enjoyable as the trip itself. So when some friends and I decided to visit New Guinea, we spent a lot of time thinking about the birds we hoped to see. Four species topped our list: Blue Bird-of-Paradise, King-of-Saxony Bird-of-Paradise, Southern Crowned-Pigeon, and Wattled Ploughbill.

The first two, at least, should come as no surprise to anyone familiar with the avifauna of New Guinea. The island is renowned for its birds-of-paradise, many of which sport spectacular colors and feathered “ornaments” of various sizes and shapes. The Blue Bird-of-Paradise in particular is a magnificent animal, with its velvet-black head, sky-blue wings, and delicate lacework of gold and blue feathers across its back. The male King-of-Saxony Bird-of-Paradise sports two outrageously long, odd-shaped feathers that extend from either side of its head, which it can twirl around like antennae during displays.

And most bird watchers, I think, would share our enthusiasm for the Southern Crowned-Pigeon, one of four species of giant, powder-blue pigeons with lacy crests that inhabit the lowland forests of New Guinea. Vulnerable to overhunting, they have disappeared near most settled areas, so finding one requires a trip to the more remote, unsettled parts of this already remote region.

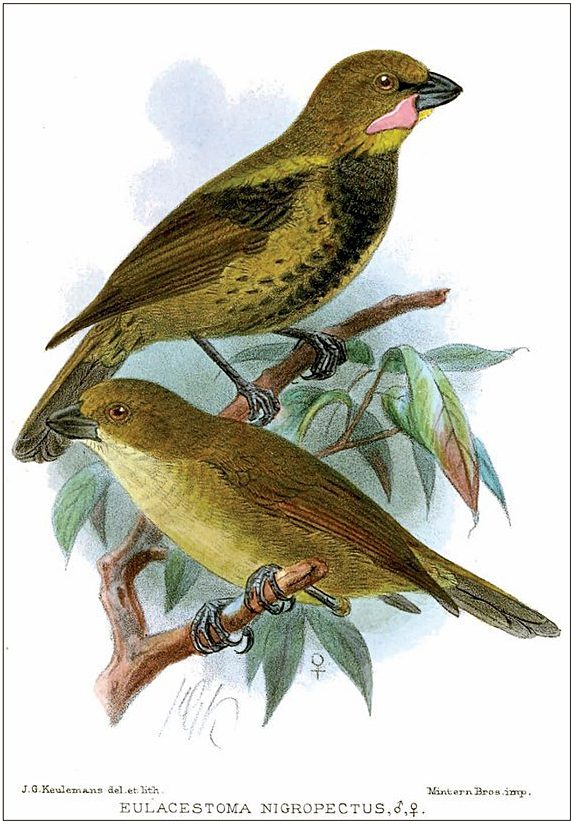

But the Wattled Ploughbill? Why would we care about seeing a sparrow-sized green-and-black bird whose only notable feature is two pink fleshy wattles hanging from either side of its face? The answer has to do with the bird’s evolutionary distinctiveness. Ornithologists have long puzzled over where to “place” the ploughbill. Some considered it to be an odd member of the whistler family (Pachycephalidae), a heterogeneous group of small to medium-sized songbirds that occur in Southeast Asia, Australia, New Guinea, and various islands in the central and south Pacific. Others have more or less thrown up their hands and labeled it a bird of “uncertain affinities.”

Over the past decade, however, the explosive growth of molecular systematics, which uses DNA sequencing to deduce genetic relatedness, has revolutionized our understanding of the evolution and diversification of the different types of birds. Most bird watchers are at least vaguely aware of this revolution, if only because it has resulted in a major reshuffling of the birds in their field guides, pushing the loons farther into the interior pages, yanking the falcons away from the hawks and depositing them closer to the songbirds, and turning the last few pages of tanagers, cardinals, buntings, and the like into a strange new jumble. It’s confusing to be sure, but it’s also fascinating.

As a consequence of molecular systematics, quite a few avian “oddities” that were previously placed somewhat uncomfortably into existing families are now thought to be long-isolated lineages that deserve to be recognized as such. In the case of the Wattled Ploughbill, the data suggest it is not all that closely related to the whistlers. Rather, it forms a distinct and lonely branch within a cluster that includes crows, birds-of-paradise, and monarch flycatchers. Indeed, it is so different that it probably deserves to be in its own family, which is precisely why we were so keen to see it. Like most bird watchers, we are drawn to birds not solely for their beauty or rarity, but also for their amazing diversity. Seeing representatives of the different bird lineages, whether they are puffins, parrots, or painted-snipes, is part of the joy of bird watching.

This aesthetic sensibility also has important parallels in conservation. Given the finite resources available for conservation, decision-makers such as the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service or BirdLife International must decide how best to allocate scarce dollars for saving endangered species. A simple rule of thumb would be to allocate the most money to the species with the greatest risk of extinction—to the rarest of the rare. But that approach quickly runs afoul of a set of practical considerations: How likely is the species to respond to conservation efforts? How expensive will it be to acquire the habitat, reduce the pollution, or do whatever is necessary to save the species? And, most importantly, what are the opportunity costs associated with protecting a particular species—i.e., which endangered species will not be helped because we have decided to dedicate our money to this one?

This last question, in turn, forces us to think more about what we aspire to protect when we protect endangered species. Is our goal to protect as many species as possible or to protect as much of earth’s evolutionary history as possible? The two goals do not necessarily result in the same set of priorities. This issue, which has been on the minds of conservation scientists for a number of years, was elegantly discussed in a 1990 paper entitled “Taxonomy as Destiny,” by Oxford ecologist Robert M. May.

May took as his starting point the strange, iguana-like reptiles called tuataras. Native to New Zealand, the two surviving species of tuataras represent the sole surviving members of an ancient order of reptiles, the Rhyncocephalia. In the world of reptiles, they are roughly as distinctive as kiwis or mousebirds are in the world of birds. Moreover, both species of tuataras are endangered, largely as a result of predation by non-native animals introduced to New Zealand. Of course, there are plenty of other endangered reptiles in the world, some much more so than the tuataras. May posed the question of whether we should value, say, the yellow-lipped grass anole, a critically endangered Anolis lizard, as much as either tuatara, given that there are hundreds of species of Anolis lizards, most of which are quite common. Losing either tuatara, he argued, would represent a loss of much more of reptilian evolutionary history than the loss of any Anolis lizard.

Now let’s consider two of the United States’ rarest birds: Northern Spotted Owl and California Condor. In terms of genetic distinctiveness, the condor is the clear winner, because it is the only member of its genus and it belongs to a small family (the New World vultures, or Cathartidae). The Northern Spotted Owl, on the other hand, represents one subspecies of one species in a genus containing about 16 species in a rather large family. As a branch of avian evolutionary history—a twig, really—it is not highly significant. But, as everyone knows, this endangered subspecies was instrumental in the protection of millions of acres of the last ancient forests of the Pacific Northwest. Thousands of species have surely benefited from our efforts to save the Northern Spotted Owl. (In all fairness to the condor, it too has been the catalyst for protecting some beautiful wilderness areas that harbor thousands of species.) In addition to absolute rarity and evolutionary distinctiveness, therefore, we might want to consider the ancillary benefits of protecting a particular species, including the other species that are likely to benefit from our actions. In that respect, both the condor and Northern Spotted Owl are effective “umbrella species”: protecting their habitat confers benefits to many other species.

There is also the matter of beauty, which we also value a great deal. It is difficult to imagine not doing everything possible to save the Whooping Crane, for example, regardless of how evolutionarily distinctive it is or how many other species stand to benefit from its conservation. Moreover, who knows how many people have been inspired to think about and support conservation thanks to this charismatic bird? Such benefits are hard to quantify but important nonetheless.

If I seem indecisive about the merits of these different approaches to determining conservation priorities, it’s because I am. Difficult choices need to be made, but no one approach to making them strikes me as inherently superior to all the others. The U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service uses a formula to determine its priorities for recovering endangered species, assigning each species points based on the urgency of the threats, the potential for the species to be recovered, and its taxonomic distinctiveness. It’s a reasonable approach, although one can easily think of additional criteria that could be added.

Returning to New Guinea, my friends and I found the Blue Birdof-Paradise near Mount Hagen, and it was every bit as beautiful as we imagined. We could not have asked for a finer look, as one perched out in the open in a nearby tree, calling incessantly, for more than an hour. The King-of-Saxony Bird-of-Paradise kept its distance, but through a telescope we were nonetheless able to see the pint-sized male twirl around its remarkable head plumes. The Southern Crowned-Pigeon required a little more effort to find—an all-day boat trip down the Fly River, which we spent scanning the riverbanks until a crowned-pigeon finally flushed from the ground and perched in a low tree.

Perhaps appropriately, the obscure Wattled Ploughbill gave us the hardest time of all. Despite several days of intense searching, we did not stumble upon it until the last afternoon, when we finally spotted a male quietly moving through the understory. The pink cheek wattles were bigger and brighter than expected, but it was otherwise, well, a little oliveand-black bird—a little olive-and-black bird with a history all its own.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library