A Golden Plan to Turn Around the Golden-winged Warbler’s Decline

By Gustave Axelson

April 15, 2013

Henry Streby crept back from the little nest cup woven among the grasses with a cloth bag in his hands. From inside the bag came an urgent buzzing sound—they were Golden-winged Warbler nestlings, calling for help.

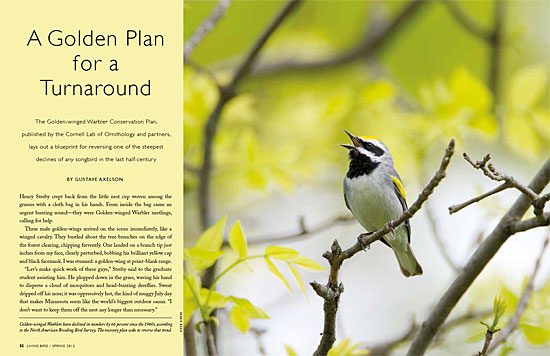

Three male golden-wings arrived on the scene immediately, like a winged cavalry. They bustled about the tree branches on the edge of the forest clearing, chipping fervently. One landed on a branch tip just inches from my face, clearly perturbed, bobbing his brilliant yellow cap and black facemask. I was stunned: a golden-wing at point-blank range.

“Let’s make quick work of these guys,” Streby said to the graduate student assisting him. He plopped down in the grass, waving his hand to disperse a cloud of mosquitoes and head-buzzing deerflies. Sweat dripped off his nose; it was oppressively hot, the kind of muggy July day that makes Minnesota seem like the world’s biggest outdoor sauna. “I don’t want to keep them off the nest any longer than necessary.”

Reaching into the bag, Streby gingerly pulled out a tiny nestling. Not yet golden, it had dark-olive plumage with faint yellow wingbars. The baby golden-wing squirmed and peeped in Streby’s hand as he flipped it on its back and gently threaded a pair of minuscule elastic bands around its delicate little legs. He was outfitting the bird with a nano-sized radio transmitter backpack. After fledging, the bird would carry the pack and contribute data to Streby’s research for a University of Minnesota study on Golden-winged Warbler breeding in the Tamarac National Wildlife Refuge.

“Done. How’s that fit?” Streby asked the little golden-wing. In his hands, he held a piece of treasure, a thus-far successfully raised young-of-the-year, a little plus sign in the bigger picture of a species suffering a massive subtraction—one of the biggest population declines of any songbird over the past 45 years.

At about 400,000 breeding individuals, Golden-winged Warblers have one of the smallest populations of any landbird not on the Endangered Species list, though that may be about to change. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) is currently considering listing the species. Minnesota has the highest remaining density of golden-wings, about half of the global population, which is why the USFWS is funding Streby’s research project.

“They want to know what’s going well here, what habitats they’re using, and how they’re surviving, so they can apply that knowledge throughout the golden-wing’s range,” Streby said.

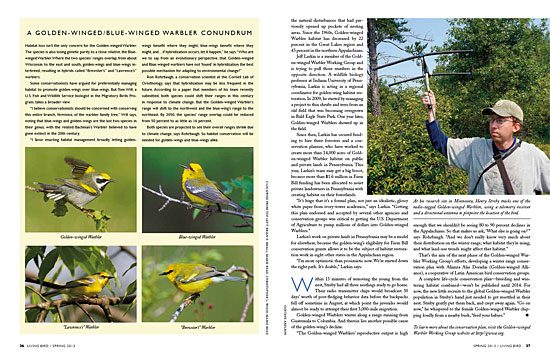

His work is part of a much larger effort by the Golden-winged Warbler Working Group, a consortium of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and 140 other universities, government agencies, and conservation groups, all dedicated to studying and saving this dwindling species. Golden-wings have declined in numbers by 66 percent since the 1960s, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The Appalachian Mountains regional population has nearly been extirpated (down 98 percent).

A final Endangered Species listing decision may be several years off, but the Golden-winged Warbler Working Group isn’t waiting to move forward on a recovery plan with a bold goal—stopping the decline, and increasing the bird’s population 50 percent by the year 2050.

“If the Golden-winged Warbler is the patient and we’re the doctors, our goal is to keep it out of intensive care,” says Cornell Lab conservation scientist Ron Rohrbaugh, a working-group leader. “We don’t want to wait around for others to act, because then it could be too late.”

Earlier in the day I had tagged along with Streby as he chased a golden-wing fledgling through aspen-oak woods with a thick understory of hazel brush. For decades the species was thought to be an early successional specialist, a creature living solely in open shrubby areas. But this bird had led us into a dense thicket. Streby crashed and bushwhacked, pausing every minute or so to hold up what looked like a mini–TV antenna, part of his radio telemetry unit. Beep-beep-beep—the unit let Streby know his antenna was pointed directly at the tiny juvenile warbler wearing a transmitter. But all we could see was brush.

Then above us, an immature golden-wing flew to a branch. Streby made a mark in his notebook. Every day for the past three summers, Streby and his crew of college student assistants have made these rounds to locate tagged birds and verify they’re still alive. We were about to leave when something else hopped up on a nearby branch, a brown-streaked bird about twice the size of the warbler.

“Check it out, Ovenbird,” Streby said. “The literature says that never the two shall meet, Ovenbird and Golden-winged Warbler.”

But they actually might hang out together in mature forests quite a bit. Streby’s telemetry tracking data show that even though Golden-winged Warblers are often born and raised in nests in open shrubby habitat, they tend to seek cover soon after fledging. He thinks mature forests with dense understories offer better protection from predators such as hawks. “

It’s not that they’re mature forest specialists, or early successional specialists, but they’re diverse forest birds,” Streby said.

That was one of the major findings of the Golden-winged Warbler Working Group’s extensive research initiative—these birds require a mosaic of forest ages. The group’s research started in 1999 with a Cornell Lab atlas project to map golden-wing distribution across its eastern North American range. In 2008, a more focused, follow-up research effort analyzed site-specific golden-wing habitat characteristics at eight study areas from Minnesota to New York and south to Tennessee.

The group’s research findings were rolled into a Golden-winged Warbler Conservation Plan, published in 2012, which includes 11 sets of localized land management instructions for creating golden-wing habitat. The plan thinks big—with goals to create an additional one million acres of habitat, resuscitate the Appalachian Mountains subpopulation by doubling its number of breeding adults, and add another 200,000 individual golden-wings to the total population, all by the middle of this century.

“We have the science to back this up, now it’s a matter of translating our science into managing habitat,” says Rohrbaugh. “We asked ourselves, ‘What do we need to do to get the population back to a healthy, sustainable level?’ And we ended up with a goal to get the population back to about where it was in the 1980s.”

The plan hopes to reverse the attrition of golden-wing habitat. Historically, periodic disturbances would create habitat—wildfires or flooding from beaver dams created patchwork shrubby openings amid a largely forested landscape. The early 20th century was good to golden-wings, when settlers cleared forest openings for settlement and farming. But as the century wore on, many cleared areas succeeded back into forests. And humans prevented the natural disturbances that had previously opened up pockets of nesting areas. Since the 1960s, Golden-winged Warbler habitat has decreased by 22 percent in the Great Lakes region and 43 percent in the northern Appalachians.

Jeff Larkin is a member of the Golden-winged Warbler Working Group and is trying to pull those numbers in the opposite direction. A wildlife biology professor at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Larkin is acting as a regional coordinator for golden-wing habitat restoration. In 2009, he started by managing a project to thin shrubs and trees from an old field that was becoming overgrown in Bald Eagle State Park. One year later, Golden-winged Warblers showed up in the field.

Since then, Larkin has secured funding to hire three foresters and a conservation planner, who have worked to create more than 14,000 acres of Golden-winged Warbler habitat on public and private lands in Pennsylvania. This year, Larkin’s team may get a big boost, because more than $1.6 million in Farm Bill funding has been allocated to assist private landowners in Pennsylvania with creating habitat on their forestlands.

“It’s huge that it’s a formal plan, not just an idealistic, glossy white paper from ivory-tower academics,” says Larkin. “Getting this plan endorsed and accepted by several other agencies and conservation groups was critical to getting the U.S. Department of Agriculture to pump millions of dollars into Golden-winged Warblers.”

Larkin’s work on private lands in Pennsylvania may be a model for elsewhere, because the golden-wing’s eligibility for Farm Bill conservation grants allows it to be the subject of habitat restoration work in eight other states in the Appalachian region.

“I’m more optimistic than pessimistic now. We’re started down the right path. It’s doable,” Larkin says.

Within 15 minutes of removing the young from the nest, Streby had all three nestlings ready to go home. Their radio transmitter chips would broadcast 30 days’ worth of post-fledging behavior data before the backpacks fell off sometime in August, at which point the juveniles would almost be ready to attempt their first 3,000-mile migration. Golden-winged Warblers winter along a range running from Guatemala to Colombia. And therein lies another possible cause of the golden-wing’s decline.

“The Golden-winged Warblers’ reproductive output is high enough that we shouldn’t be seeing 80 to 90 percent declines in the Appalachians. So that makes us ask, ‘What else is going on?’ ” says Rohrbaugh. “And we don’t really know very much about their distribution on the winter range, what habitat they’re using, and what land-use trends might affect that habitat.”

That’s the aim of the next phase of the Golden-winged Warbler Working Group’s efforts, developing a winter range conservation plan with Alianza Alas Doradas (Golden-winged Alliance), a cooperative of Latin American bird conservation groups.

A complete life-cycle conservation plan—breeding and wintering habitat combined—won’t be published until 2014. For now, the new little recruits to the global Golden-winged Warbler population in Streby’s hand just needed to get resettled in their nest. Streby gently put them back, and crept away again. “Go on now,” he whispered to the female Golden-winged Warbler chipping loudly from a nearby bush, “feed your babies.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library