Female Birds-of-Paradise Go For Complex Males

By Kathi Borgmann and Pat Leonard

December 17, 2018From the Winter 2019 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Male birds-of-paradise are world famous for their showmanship—their wildly extravagant plumage, their complex vocal arrangements, and their shape-shifting dance moves. They’ve starred in their own prime-time TV documentary, been splashed across the pages of National Geographic Magazine, even amazed museum-goers in a traveling exhibit that drew big crowds as it toured the nation.

New research published in the journal PLOS Biology suggests for the first time that everything in those theatrical breeding displays by the males is driven by one thing: the female. It’s female preferences for a combination of looks and moves that drive the evolution of the extreme physical and behavioral trait combinations observed in the birds-of-paradise.

A team led by Cornell Lab of Ornithology postdoctoral researcher Russell Ligon examined almost 1,000 video clips and 200 audio clips from the Cornell Lab’s Macaulay Library of natural history media, along with nearly 400 specimens from New York City’s American Museum of Natural History, to analyze the richness and diversity of the colors, dancing, and sounds of breeding displays by male birds-of-paradise.

Their results suggest that female birds-of-paradise evaluate multiple aspects of a male’s breeding display at once. The females don’t just consider how great the male looks, but also how well he sings and dances. Female preferences for certain combinations of these traits—such as electric-blue feathers displayed during a promenade around the forest floor, or elaborate plumes flared out during an excited bout of hopping and high-volume squawking—result in what the researchers call a “courtship phenotype,” or a bundle of physical and behavioral traits during breeding displays.

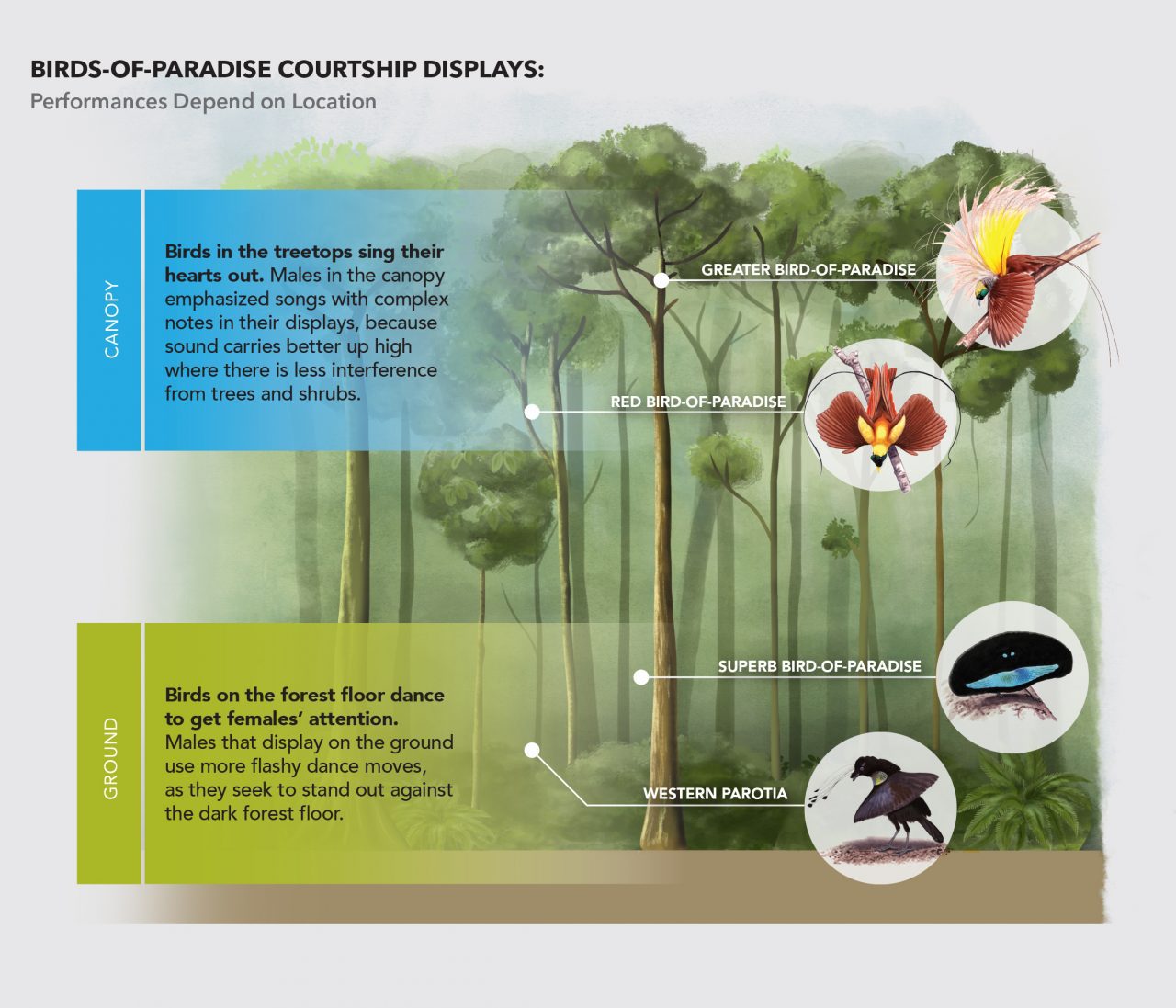

Ligon and his colleagues also discovered that where a male performs his breeding displays seems to affect the behavior in the display. “Species that display on the ground have more dance moves than those displaying in the treetops,” said Edwin Scholes, study coauthor and Cornell Lab Birds-of-Paradise Project research leader. “On the dark forest floor, males may need to up their game to get female attention.”

On the other hand, males in the treetops sang more complex notes during their displays, because sound carries better up high where there is less interference from trees and shrubs. But their dances were less elaborate—perhaps a nod to the risks of dancing on a wobbly branch.

There are 40 known species of birds-of-paradise, mostly found in New Guinea and northern Australia. This unique and isolated family of birds had the opportunity to evolve outlandish male breeding displays thanks to the absence of mammalian competitors. Since the birds didn’t have to worry about fighting over fruit with monkeys and squirrels, females could spend more time choosing a mate. More time spent evaluating mates pushes males to stand out from others, whether through voice, feathers, or dance.

This research stands out as the first to suggest that it is the combination of physical and behavioral traits that enables elaborate plumages and behaviors to evolve in the first place. Because females choose males based on more than one characteristic, Ligon says, evolution favored “fancier and fancier males.”

Reference:

R. A. Ligon, C. D. Diaz, J. L. Morano, J. Troscianko, M. Stevens, A. Moskeland, T. G. Laman, and E. Scholes III. 2018. Evolution of correlated complexity in the radically different courtship signals of birds-of-paradise. PLOS Biology.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library