Can We Save the Birds of Bonkro, Africa?

By George Oxford Miller

July 15, 2013

The village of Bonkro in Ghana has no city limits sign to welcome us, and doesn’t need one—a horde of excited kids runs to greet us. After an hour’s drive down a rutted, red-dirt two-track road, scarred with potholes, we reach the small settlement of mud houses. Fifty or more yelling, jumping, laughing children surround our van and scramble alongside as we bump into the village. They pose for photos and crowd around to see themselves on our tiny camera screens. A woman dressed in the brightly patterned fabric popular throughout Africa watches the commotion with amusement as she stirs a pot of gari, a cassava mush, over an open fire. Soon most of the village wanders up to see the visitors.

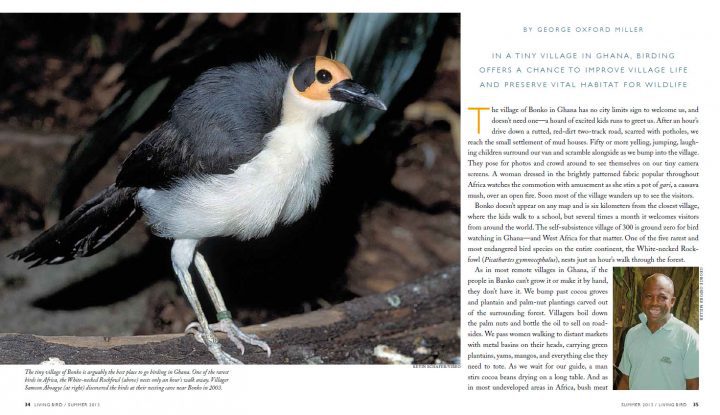

Bonkro doesn’t appear on any map and is six kilometers from the closest village, where the kids walk to a school, but several times a month it welcomes visitors from around the world. The self-subsistence village of 300 is ground zero for bird watching in Ghana—and West Africa for that matter. One of the five rarest and most endangered bird species on the entire continent, the White-necked Rockfowl (Picathartes gymnocephalus), nests just an hour’s walk through the forest.

As in most remote villages in Ghana, if the people in Bonkro can’t grow it or make it by hand, they don’t have it. We bump past cocoa groves and plantain and palm-nut plantings carved out of the surrounding forest. Villagers boil down the palm nuts and bottle the oil to sell on roadsides. We pass women walking to distant markets with metal basins on their heads, carrying green plantains, yams, mangos, and everything else they need to tote. As we wait for our guide, a man stirs cocoa beans drying on a long table. And as in most undeveloped areas in Africa, bush meat provides an important supplement to the chickens and goats that freely roam the village lanes.

Bonkro borders a large section of government-owned forest with a fairly intact canopy and a healthy bird population. In Ghana, 80 to 90 percent of canopy forest has been converted into farmland. Intact rainforest with pristine emergent canopy and understory layers of tree cover survives only in national parks and protected reserves. Like the U. S. Forest Service in America, the government grants licenses for logging in the remaining forests. During two weeks of birding in remote areas, we often had to step aside as forest giants with six-foot-diameter trunks rolled past on logging trucks.

In a few minutes, our local guide, Samson Aboagye, joins us. In 2003, the young man made a life-changing discovery in the nearby forest.

“I was hunting for bush meat and saw some beautiful birds that I had never seen before,” he says as we start down the path. “I know all the birds, I just don’t have names for them, but these were new. Seven, eight, nine, ten of them came by on their way to roost for the night.”

Samson alerted a Ghana Wildlife Department biologist, who observed the birds and verified their identification. Earlier that year, one had been trapped at the protected Subim Forest Reserve in the Brong-Ahafo Region. Before these two sightings, Picathartes gymnocephalus hadn’t been seen in Ghana since the 1960s and was considered extinct in the country.

Disjunct populations of Picathartes live in the semi-deciduous Upper Guinean rainforest that extends a few hundred kilometers inland from the coast in Sierra Leone, Guinea, Liberia, Ivory Coast, and Ghana. Designated a Biodiversity Hotspot by Conservation International, the region harbors more than 700 bird species, including 15 endemics. This rich variety of birdlife adds an exciting bonus for birders who come to Ghana primarily to see the White-necked Rockfowl.

Little is known about the habitat requirements, food preferences, reproduction, or life history of the birds. Studies indicate that they typically lay two eggs in the rainy season, but an average of only 0.44 nestlings survive per nest, which suggests that depressed populations would be slow to recover. BirdLife International estimates the world population at between 2,500 and 10,000. In a 2007 Earthwatch report, only 18 pairs were observed in 22 colonies in the Ghana study area.

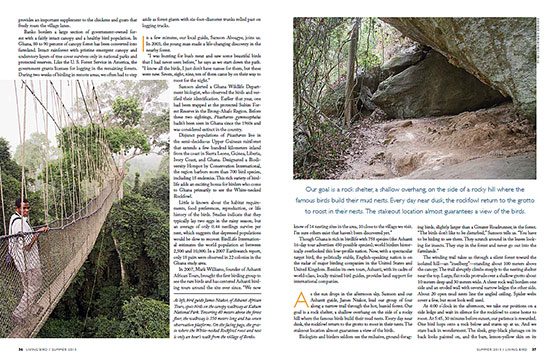

In 2007, Mark Williams, founder of Ashanti African Tours, brought the first birding group to see the rare birds and has centered Ashanti birding tours around the site ever since. “We now know of 14 nesting sites in the area, 10 close to the village we visit. I’m sure others exist that haven’t been discovered yet.”

Though Ghana is rich in birdlife with 758 species (the Ashanti 16-day tour advertises 450 possible species), world birders historically overlooked this low-profile nation. Now, with a spectacular target bird, the politically stable, English-speaking nation is on the radar of major birding companies in the United States and United Kingdom. Besides its own tours, Ashanti, with its cadre of world-class, locally trained bird guides, provides land support for international companies.

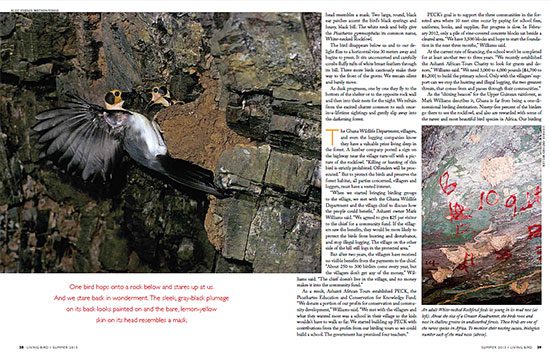

As the sun drops in the afternoon sky, Samson and our Ashanti guide, James Ntakor, lead our group of four along a narrow trail through the hot, humid forest. Our goal is a rock shelter, a shallow overhang on the side of a rocky hill where the famous birds build their mud nests. Every day near dusk, the rockfowl return to the grotto to roost in their nests. The stakeout location almost guarantees a view of the birds.

Biologists and birders seldom see the reclusive, ground-foraging birds, slightly larger than a Greater Roadrunner, in the forest. “The birds don’t like to be disturbed,” Samson tells us. “You have to be hiding to see them. They scratch around in the leaves looking for insects. They stay in the forest and never go out into the farmlands.”

The winding trail takes us through a silent forest toward the isolated hill—an “inselberg”—standing about 100 meters above the canopy. The trail abruptly climbs steeply to the nesting shelter near the top. Large, flat rocks protrude over a shallow grotto about 10 meters deep and 30 meters wide. A sheer rock wall borders one side and an eroded wall with several narrow ledges the other side. About 20 open mud nests line the angled ceiling. Spider webs cover a few, but most look well used.

At 4:00 o’clock in the afternoon, we take our positions on a side ledge and wait in silence for the rockfowl to come home to roost. At 5:45, 30 minutes before sunset, our patience is rewarded. One bird hops onto a rock below and stares up at us. And we stare back in wonderment. The sleek, gray-black plumage on its back looks painted on, and the bare, lemon-yellow skin on its head resembles a mask. Two large, round, black ear patches accent the bird’s black eyerings and heavy, black bill. The white neck and belly give the Picathartes gymnocephalus its common name, White-necked Rockfowl.

The bird disappears below us and to our delight flies to a horizontal vine 30 meters away and begins to preen. It sits unconcerned and carefully combs fluffy tufts of white breast feathers through its bill. Three more birds cautiously make their way to the front of the grotto. We remain silent and barely move.

As dusk progresses, one by one they fly to the bottom of the shelter or to the opposite rock wall and then into their nests for the night. We refrain from the excited chatter common to such once-in-a-lifetime sightings and gently slip away into the darkening forest.

The Ghana Wildlife Department, villagers, and even the logging companies know they have a valuable prize living deep in the forest. A lumber company posted a sign on the highway near the village turn-off with a picture of the rockfowl. “Killing or hunting of this bird is strictly prohibited. Offenders will be prosecuted.” But to protect the birds and preserve the forest habitat, all parties concerned, villagers and loggers, must have a vested interest.

“When we started bringing birding groups to the village, we met with the Ghana Wildlife Department and the village chief to discuss how the people could benefit,” Ashanti owner Mark Williams said. “We agreed to give $25 per visitor to the chief for a community fund. If the villagers saw the benefits, they would be more likely to protect the birds from hunting and disturbance, and stop illegal logging. The village on the other side of the hill still logs in the protected area.”

But after two years, the villagers have received no visible benefits from the payments to the chief. “About 250 to 300 birders come every year, but the villagers don’t get any of the money,” Williams said. “The chief doesn’t live in the village, and no money makes it into the community fund.”

As a result, Ashanti African Tours established PECK, the Picathartes Education and Conservation for Knowledge Fund. “We donate a portion of our profits for conservation and community development,” Williams said. “We met with the villagers and what they wanted most was a school in their village so the kids wouldn’t have to walk so far. We started building up PECK with contributions from the profits from our birding tours so we could build a school. The government has promised four teachers.”

PECK’s goal is to support the three communities in the forested area where 10 nest sites occur by paying for school fees, uniforms, books, and supplies. But progress is slow. In February 2012, only a pile of vine-covered concrete blocks sat beside a cleared area. “We have 3,500 blocks and hope to start the foundation in the next three months,” Williams said.

At the current rate of financing, the school won’t be completed for at least another two to three years. “We recently established the Ashanti African Tours Charity to look for grants and donors,” Williams said. “We need 3,000 to 4,000 pounds [$4,700 to $6,200] to build the primary school. Only with the villagers’ support can we stop the hunting and illegal logging, the two greatest threats, that comes from and passes through their communities.”

As the “shining beacon” for the Upper Guinean rainforest, as Mark Williams describes it, Ghana is far from being a one-dimensional birding destination. Ninety-five percent of the birders go there to see the rockfowl, and also are rewarded with some of the rarest and most beautiful bird species in Africa. Our birding adventure began in the 360-square-kilometer Kakum National Park, near Cape Coast, with an early-morning jaunt high above the rainforest canopy. The rope walkway, attached to 65-metertall emergent trees, stretches for 350 meters with seven platforms.

“Kakum is the only remnant rainforest in the area,” park biologist Eric Adu tells us. “All four forest layers—emergent, canopy, understory trees, and groundcover—are intact. We have over 300 species of birds, 8 species of antelopes, 600 species of butterflies, and 240 forest elephants.”

As the morning light brightens the forest, birds soar over our heads and under our feet. African Pied Hornbills, the bully-boys of the treetops, chase a Black-winged Oriole from a tree, then turn their attention to a giant squirrel, which scampers back into its hole in a trunk. The pterodactyl-like silhouette of the hornbills soaring against the hazy sky becomes the icon for our African adventure. During our trip, we see eight of the nine hornbill species in the area.

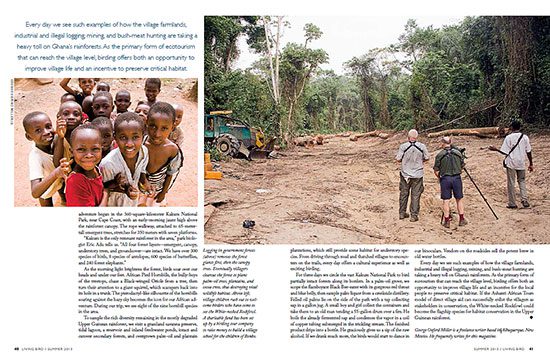

To sample the rich diversity remaining in the mostly degraded Upper Guinean rainforest, we visit a grassland savanna preserve, tidal lagoon, a reservoir and inland freshwater ponds, intact and cutover secondary forests, and overgrown palm-oil and plantain plantations, which still provide some habitat for understory species. From driving through mud and thatched villages to encounters on the trails, every day offers a cultural experience as well as exciting birding.

For three days we circle the vast Kakum National Park to bird partially intact forests along its borders. In a palm-oil grove, we scope the flamboyant Black Bee-eater with its gorgeous red throat and blue belly, then sample palm liquor from a creekside distillery. Felled oil palms lie on the side of the path with a tap collecting sap in a gallon jug. A small boy and girl collect the containers and take them to an old man tending a 55-gallon drum over a fire. He boils the already fermented sap and condenses the vapor in a coil of copper tubing submerged in the trickling stream. The finished product drips into a bottle. He graciously gives us a sip of the raw alcohol. If we drank much more, the birds would start to dance in our binoculars. Vendors on the roadsides sell the potent brew in old water bottles.

Every day we see such examples of how the village farmlands, industrial and illegal logging, mining, and bush-meat hunting are taking a heavy toll on Ghana’s rainforests. As the primary form of ecotourism that can reach the village level, birding offers both an opportunity to improve village life and an incentive for the local people to preserve critical habitat. If the Ashanti African Tours model of direct village aid can successfully enlist the villagers as stakeholders in conservation, the White-necked Rockfowl could become the flagship species for habitat conservation in the Upper Guinean rainforest.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library