View from Sapsucker Woods: Grinnell’s Mantra Rings True on a Peruvian Mountain

By John W. Fitzpatrick

December 20, 2018

From the Winter 2019 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Two years ago I described in this column my emotional return to a Peruvian mountain ridge where I had worked 30 years earlier. Back in the 1980s, my Field Museum colleagues and I carefully documented abundances and elevational limits for hundreds of bird species found along that forested mountain transect. In 2016, with recent Cornell PhD student Ben Freeman and others, we relocated our 1985 base camp and survey route up the mountain. In 2017, Ben and several colleagues mist-netted and censused birds from the lowlands to the ridgetop, taking care to repeat our earlier protocols as faithfully as possible. The sobering results of this resurvey were recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal and are summarized in a story in this issue.

It would be fair to ask if Ben’s “escalator to extinction” is an isolated case, perhaps reflecting unmeasured habitat perturbations affecting a few bird distributions on a mountaintop. Indeed, scientists avoid drawing conclusions from a small sample size. To the contrary, Ben compared historical and modern elevations for more than a hundred of the most common species on this mountain and found pervasive upslope shifts that were independent of body size, foraging stratum, or diet. Moreover, the scale of these shifts corresponded remarkably with those predicted for a region where average temperature had risen almost half a degree Celsius since 1985.

The extirpations documented in the paper received many media headlines—the team could not find eight of the mountaintop bird species we surveyed 30 years ago—but another striking pattern in their data was even more illuminating. Most of the upper-elevation species that still existed on the mountain had declined considerably in abundance. Shockingly, for example, our most commonly mist-netted species near the mountaintop in 1985 (Russet-crowned Warbler, Myiothlypis coronata) is now limited to the very top of the ridge and declined by more than 70 percent. With shrinking ranges and declining numbers, upper-elevation bird species grow ever more vulnerable to local disappearance. In contrast, species occurring farther down the slope on average have not experienced declines, and many actually increased in abundance as their upper elevational limits moved higher. What will be their fate decades from now?

Ben’s 2017 resurvey was not his first rodeo. Two heroic resurveys that he and his wife, Alexa, conducted in New Guinea in 2012 also documented astonishing upslope shifts. That work signaled the urgent need to test for the global generality of the pattern, because tropical mountains harbor more species than any other terrestrial environment on earth. If these “escalators” are occurring at tropical latitudes everywhere, then biodiversity loss from climate change will be far more rapid and pronounced than originally modeled.

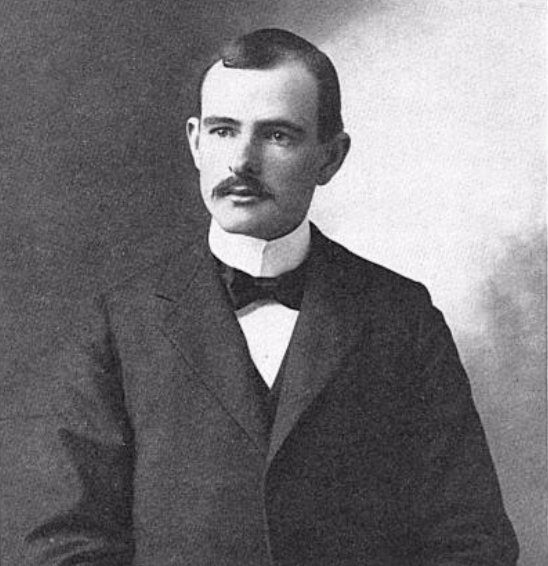

It is clear that more resurveys are in order now, given their importance in understanding the complex biology set in motion by climate change. The catch is that we cannot go back in time to gather “before” data. Resurveys are only informative where well-documented distribution and abundance data already exist from an earlier era, and these are rare. An extraordinary recent example is the comprehensive resurvey of California valleys and mountains traversed a century ago by the legendary naturalist Joseph Grinnell, who famously emphasized meticulous record-keeping and thorough documentation.

Ben Freeman is scouring the world for more resurvey opportunities. His search constitutes a clarion call about the importance of carefully documenting species distributions, movements, abundances, and population trends—right now. Today’s present is tomorrow’s past, and the world is changing more rapidly than ever. Our Field Museum team did not imagine in the early 1980s that our data—gathered for other purposes— could help reveal globally significant impacts of climate change. None of us can predict what the data we carefully gather and archive today will help reveal decades or centuries from now. What we can and must do is adhere to Grinnell’s commitments: document nature extensively and in detail and ensure that future generations will have access to what we are encountering today.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library