Some Chickadees Are Bilingual—But Why?

By Jack Connor April 15, 2008

The first scientist to report bilingual singing in chickadees seems to have been James Tanner, who reported the phenomenon in a 1952 article in The Auk: “Black-capped and Carolina chickadees in the Southern Appalachian Mountains.”

“In the early morning of April 18, 1949, in the Great Smoky Mountains at an elevation of about 2,800 feet, I heard a chickadee rapidly repeating a fairly typical Carolina song, and then suddenly it switched to a typical black-capped song, pitched much lower,” wrote Tanner. “It continued this song as it moved rapidly up the slope. From subsequent observations and collections of birds in that area, I suspect it was a young Black-capped Chickadee that had wintered at the elevation or lower in company with Carolina Chickadees.”

Tanner is best known today for his study of the rarest of the rare, the Ivory-billed Woodpeckers at Louisiana’s Singer Tract in the late 1930s. A decade later, he spent three winters and springs (1948 to 1950) in the mountains of Tennessee pursuing two of North America’s most common birds and helped to spark an investigation that continues today.

If you have birded on either side of the 1,500-mile-long boundary running from northeastern New Jersey to southwestern Kansas, which ostensibly separates the ranges of our two most look-alike chickadees, you have probably considered the same questions as Tanner: “Do [black-caps and Carolinas] intermingle and perhaps interbreed? If [not], what factors operate to keep them separate?” If you have spent enough time inside the narrow zone where their ranges overlap and both species are possible, you may even have heard chickadees whose songs were hard to place. Is that a black-cap, a Carolina, or both?

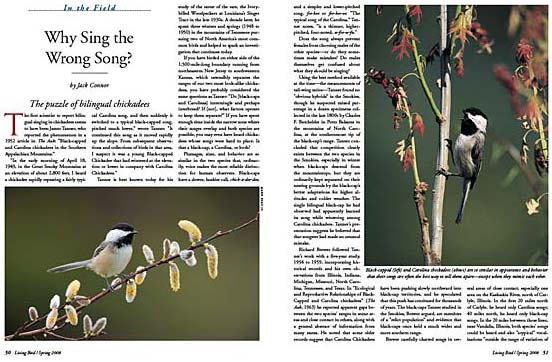

Plumages, sizes, and behavior are so similar in the two species that, ordinarily, voice makes the most reliable distinction for human observers. Black-caps have a slower, huskier call, chick-a-dee-dee, and a simpler and lower-pitched song, fee-bee or fee-bee-ee. “The typical song of the Carolina,” Tanner notes, “is a thinner, higher-pitched, four-noted, se-fee-se-fu.”

Does the song always prevent females from choosing males of the other species—or do they sometimes make mistakes? Do males themselves get confused about what they should be singing?

Using the best method available at the time—the measurements of tail-wing ratios—Tanner found no “obvious hybrids” in the Smokies, though he suspected mixed parentage in a dozen specimens collected in the late 1800s by Charles F. Batchelder in Potts Balsams in the mountains of North Carolina, at the southernmost tip of the black-cap’s range. Tanner concluded that competition clearly exists between the two species in the Smokies, especially in winter when black-caps descend from the mountaintops, but they are ordinarily kept separated on their nesting grounds by the black-cap’s better adaptations for higher altitudes and colder weather. The single bilingual black-cap he had observed had apparently learned its song while wintering among Carolina chickadees. Tanner’s presentation suggests he believed that that songster had made an unusual mistake.

Richard Brewer followed Tanner’s work with a five-year study, 1954 to 1959, incorporating historical records and his own observations from Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas. In “Ecological and Reproductive Relationships of Black-Capped and Carolina chickadees” (The Auk, 1963) he reported apparent gaps between the two species’ ranges in some areas and close contact in others, along with a general absence of information from many states. He noted that some older records suggest that Carolina Chickadees have been pushing slowly northward into black-cap territories, and he speculated that this push has continued for thousands of years. The black-caps Tanner studied in the Smokies, Brewer argued, are members of a “relict population” and evidence that black-caps once held a much wider and more southern range.

Brewer carefully charted songs in several areas of close contact, especially one area on the Kaskaskia River, north of Carlyle, Illinois. In the first 20 miles north of Carlyle, he heard only Carolina songs; 40 miles north, he heard only black-cap songs. In the 20 miles between those lines, near Vandalia, Illinois, both species’ songs could be heard and also “atypical” vocalizations “outside the range of variation of either [species].”

Brewer suspected the abnormal singing came from hybrids, and he labeled the area (and an area in Missouri where he found the same pattern) a “hybrid zone.” If we think of song as primarily a courtship device, then a male singing the “wrong” song may seem confused about his identity—as if his instincts have been cross-wired by mixed parentage. Brewer also noted, however, several instances where presumed pure-bred males of the two species responded to each other as rivals, including singing their own songs back and forth at each other “in a vocal duel that seemed identical to those of intraspecific nature.”

Rodman Ward and Dorcas A. Ward followed Brewer’s work with a five-season study of their own, 1963 to 1969, and reported their results in “Songs in Contiguous Populations of Black-capped and Carolina chickadees in Pennsylvania” (The Wilson Bulletin, 1974). The Wards had the significant advantage of tape recording and playback and used it well. Their analysis of an area along the border of Berks County and Chester County closely paralleled Brewer’s analysis in Illinois and Missouri. Only Black-capped Chickadee songs were recorded in Berks, north of the border; only Carolina Chickadee songs were recorded a dozen or more miles south of it. In between, in northwest Chester County and an adjacent area of Lancaster County, they recorded the songs of both species, as well as abnormal songs and also “duality”—individuals singing songs of both species, as Tanner’s 1949 male had done.

The Wards’ playbacks confirmed Brewer’s sense of intraspecific rivalry: within the area of contact, individual males responded aggressively to both songs. North and south of that area, each species apparently ignored recordings of the other.

Was Brewer correct in suggesting that the odd singers were hybrid birds?

“Although hybridization is perhaps the most likely cause for vocal anomalies,” the Wards concluded, “we would like to raise [the possibility] that the two species could be responding to contact by developing some degree of vocal convergence and mimicry. We admit the evidence for this theory is scant, but we feel it deserves some attention.”

More than 30 years of subsequent research has added several twists to this story, but apparently both ideas—Brewer’s idea that hybrids are numerous in the contact zone and the Wards’ that vocal convergence and mimicry are factors—have been proven correct.

Young chickadees raised in the contact zone hear both species’ songs around them, and because songs reflect learning (“nurture”) at least as much as genetics (“nature”), the birds can grow up to sing and respond to either or both songs. We should remember also that male song is generally intended as much to intimidate males as to attract females. This is especially true in chickadees because pairs apparently form in winter before singing starts. Perhaps, bilingual males hold an advantage in intimidation compared with other males in the contact zone.

In the last decade or so, the puzzle has grown even more complicated as blood samples and biochemical analysis (looking at mitochondrial DNA, among other things) have demonstrated that hybrids are very numerous in the contact zone, and more sophisticated recording has demonstrated that both aberrant and dual singing are very frequent there. A number of investigations have also found that the contact zone is moving steadily northward, as Carolinas and hybrids replace populations of pure-bred Black-capped Chickadees—at a speed of nearly a mile a year in some areas. Robert Curry and his students at Villanova University have recently re-examined the area in Berks, Chester, and Lancaster counties in Pennsylvania, where the Wards found a hybrid zone in the 1970s. Today, they discovered, you will hear only Carolina Chickadee songs there.

Space limits the discussion of these and many other related developments. For more details, see Curry’s excellent overview, “Hybridization in Chickadees: Much to Learn from Familiar Birds” (The Auk, 2005), or the new book, Ecology and Behavior in Chickadees and Titmice, edited by Ken Otter (Oxford University Press, 2007).

This puzzle should especially intrigue amateur observers because our own reports can become valuable data. The lines of the “contact zone” are much better known nowadays than they were in the 1960s and 1970s, and if you live in any midlatitude state from Kansas east, you should be able to find information on the Internet about how close the line currently stands to your favorite birding spots. You can also participate outside the contact zone—especially in areas north of it—by recording songs and the number of chickadees you find in your backyard or the nearest woodlot. See www.ebird.org for easy ways to record and compile your finds.

What’s that, you say? You have only Black-capped Chickadees in your neighborhood? Keep an ear out. Carolina Chickadees—and their hybrid offspring—have been moving northward for at least half a century and possibly since the last Ice Age. They are almost certainly headed in your direction.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library