Short Distance Migrants Have More Flexibility in Response to a Spring Heat Wave

By Pat Leonard

March 21, 2016

Weather is a wild card for travelers. If you’re heading to the local park or taking a day trip, it’s easy enough to adjust your plans if the weather turns bad or even improves. But for longer journeys, scheduled far in advance, it’s a roll of the dice as to whether you’ll enjoy balmy weather or end up taking in the sights from beneath a soggy umbrella. We may be philosophical about a less-than-perfect trip. However, for some long-distance migratory birds, the consequences of extreme weather may be severe.

“Up until recently most climate-change work has focused on changes in average temperature,” explains Cornell Lab of Ornithology scientist Frank La Sorte, lead author of a new study published in the journal Ecosphere. “People are starting to realize that birds and other animals may respond to the extremes more than to the average. An extreme event means a significant departure from the long-term norm, and climate change may result in an increase in the number and intensity of extreme weather events.”

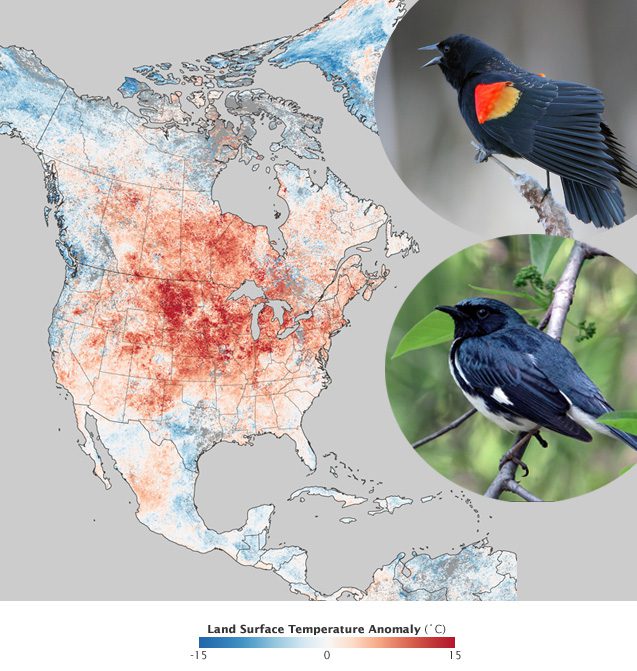

Think back to March 2012. You might recall that it was very warm with temperatures a good 10 degrees higher than usual across much of the United States and Canada. The jet stream blocked a mass of warm air and held it in the center of the continent all month—an area called the mid-latitudes. During the past century there have been only three events as extreme as the March 2012 heat wave, according to the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia.

La Sorte and colleagues looked at the responses of 353 bird species to this extreme March weather using data collected through the eBird online checklist program from 2010 through 2014. They also examined data from satellites that detect the greening and productivity of plants on the Earth’s surface. The analysis showed that 21 migratory bird species responded strongly to the warming and early greening in March 2012 and they were reported to eBird in greater numbers. They were mostly short-distance migrants such as the American Robin and Red-winged Blackbird (see complete list).

“During the warm spell everything greened up,” says La Sorte. “Short-distance migrants responded to the flush of resources in March and they benefitted from it to a certain degree.”

Because the unseasonable warmth affected a wide region, short-distance migrants likely could detect it from their wintering locations and move in to take advantage of the early greening. Thousands of miles farther south, long-distance migrants had no way to detect the unusual weather.

“Long-distance migrants have different cues that tell them when to migrate in spring, such as changes in day length that correspond to changes in hormones that prompt migratory behavior—they cannot react to distant extreme weather events over the short term,” says La Sorte.

After the March warmth, April turned cold again, resulting in lower plant productivity during July and August. Long-distance migrants were most negatively affected by this—the study found 32 species with lower-than-expected numbers during the summer of 2012. These included Black-throated Blue Warbler and White-throated Sparrow.

“The majority of the species we looked at for the study did not show a strong response to the March weather event or the subsequent decrease in summer plant productivity,” says La Sorte. “Our takeaway from this is that, yes, extreme weather does have an impact, but the number of species affected may be limited. The short-distance migrants, if they react at all, seem much more adaptable to variation in local conditions, whereas the more rigid migration schedules of long-distance migrants may place them at a distinct disadvantage.”

Additional work and analysis on other extreme weather events may bring scientists closer to understanding possible climate change effects on migratory birds.

“We know long-distance migrants cannot react in the short term to extreme weather events, but that leads to the question, what about over the long term?” says La Sorte. “If the frequency and intensity of these events increases, the negative implications documented in this study may intensify, but the exact outcome remains unclear. Bird watchers provide a valuable source of information to address this question when they submit their observations to eBird.”

Reference

Frank A. La Sorte, Wesley M. Hochachka, Andrew Farnsworth, André Dhondt, Cornell Lab of Ornithology; and Daniel Sheldon, University of Massachusetts and Mount Holyoke College. The implications of mid-latitude climate extremes for North American migratory bird populations. Ecosphere. March 2016.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library