Seeing More Hawks in Your Yard? It’s Not Your Imagination

By Marc Devokaitis

March 7, 2019

From the Autumn 2019 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Raptors—especially Cooper’s Hawks and Sharp-shinned Hawks—have become a familiar presence at urban and suburban feeders around North America. But it wasn’t always this way.

In a 2017 retrospective of Project FeederWatch results, we noted that Cooper’s Hawks increased their presence fourfold at FeederWatch sites over the past two decades. The agile accipiters occurred at just 6% of feeders in 1989, but by 2016 had increased to around 25% of feeders. Cooper’s Hawks have historically been thought of as a rural species, picking songbirds from branches in surprise attacks in the woodlands and forests. But one clear factor in the surge of FeederWatch reports has been their expansion into suburban and urban areas.

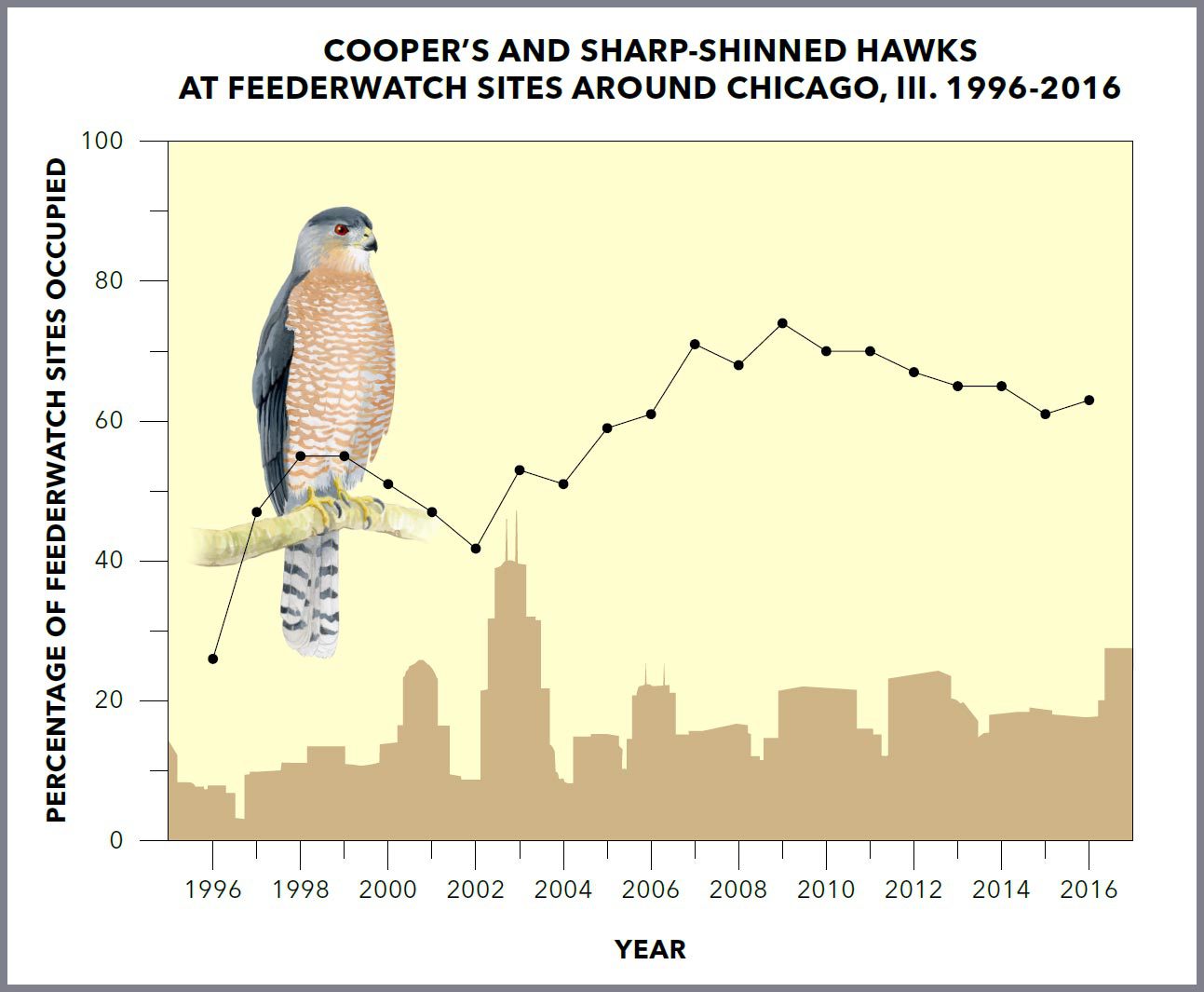

Scientists from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology took these results and went further, trying to find out what might be behind these increases. They looked at 21 years of Project FeederWatch data (1996–2016) from winters in the greater Chicago area, a period in which accipiter sightings increased from 26% to more than 60% of all feeders.

The results, published in November 2018 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, suggest that the main reason Cooper’s Hawks (as well as their petite doppelgangers, Sharp-shinned Hawks) have spread into these new environments is an increase in prey availability.

The team went into the study thinking that areas with more tree cover, fewer paved surfaces, and more prey availability would see an increase in hawks—basically, the image of a leafy suburban neighborhood with room for both songbirds and hawks. In the early years of the data, this held true, and hawks were less likely to occur in heavily urbanized areas with more paved surfaces. But then something interesting happened.

Eventually, hawks moved into (and stayed in) moderately or heavily urbanized areas, provided there was enough prey. (The researchers calculated prey abundance using Project Feederwatch data.) By the end of the study period, hawks were actually somewhat more likely to occur in places with fewer trees.

The researchers speculated that since the FeederWatch data represent the winter months, when hawks were not nesting, their primary concern was finding prey rather than nesting habitat. Since landscapes with fewer trees often have higher human populations, they might have higher numbers of bird feeders as well. By attracting and concentrating feeder birds, these areas might provide the best winter food resources for hawks as well as songbirds.

This sounds like good news for hawks, but does it mean backyard feeders are becoming more dangerous for songbirds? Emma Greig, project leader for FeederWatch, says that it’s complicated.

“As the authors point out, previous studies have shown that a lot of the birds that these hawks are taking in urban areas are invasives such as pigeons and starlings – so that could actually help native species.” Greig points out that many of the native prey species for these hawks—American Goldfinches, Dark-eyed Juncos, Northern Cardinals, and Mourning Doves, for example, all have stable populations.

“It doesn’t mean you should just let a predator wreak havoc at your feeder for weeks on end…sometimes taking a feeder down to discourage frequent attacks is a good strategy,” Greig says. “At the same time, regular visits from Cooper’s Hawks and sharpies aren’t necessarily a bad thing.” And when you’re out and about—even if you’re downtown—keep an eye out for a slim, long-tailed shape gliding inconspicuously through streets and parks. It could be one of these newly numerous urban accipiters.

Available for everyone, American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library

Reference: McCabe, J.D. et al. (2018). Prey abundance and urbanization influence the establishment of avian predators in a metropolitan landscape. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 285 (1890).

All About Birds

is a free resource

funded by donors like you