Why Do We Feed Birds—and Should We? A Q&A With the Experts

By Pat Leonard and Darien Fiorino

December 18, 2018

From the Winter 2019 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

In his book The Birds at My Table: Why We Feed Wild Birds and Why It Matters, Australian scientist Darryl Jones takes a deep dive into the history of the practice, its phenomenal growth, and some of the reasons we do it. We talked with Jones about some of the most basic questions about feeding birds: Is it good for birds? What are the risks? And what do people get out of it? To round out the conversation, we also asked Emma Greig, who leads the Lab’s own Project FeederWatch, and consulted the 2015 book Feeding Wild Birds in America, by Paul Baicich, Margaret Barker, and Carrol Henderson, as a reference.

Darryl Jones, author of The Birds at My Table. Image courtesy of the author.

Emma Greig, project leader for Project FeederWatch. Image by Daniel Hooper.

Jones's book The Birds at My Table explores the motivations of people who feed birds and the effects of the hobby.

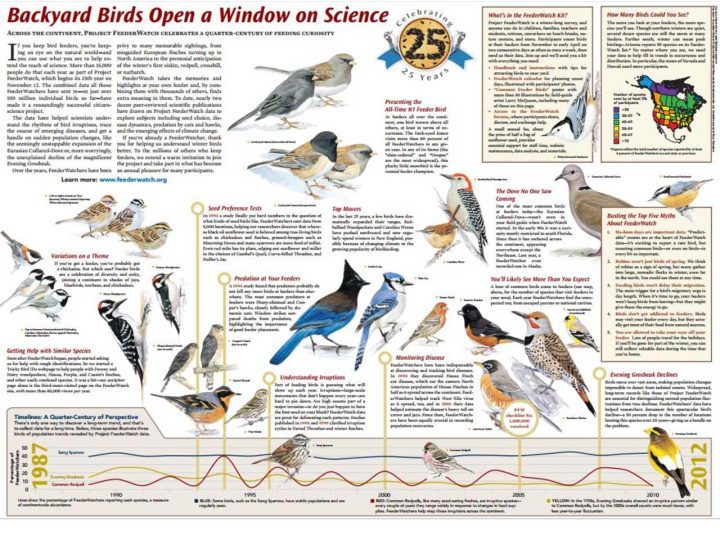

Over the project's 30+ year history, FeederWatch data has helped uncover many unexpected patterns in bird distribution. This poster outlines some of the most important.

Q: In the book, you say we know very little about feeding wild birds.

Darryl Jones: It absolutely astounded me. When I first started looking into this I thought I could just read the “300 papers about bird feeding” [that I assumed must exist], but there was just nothing there. It’s this funny global activity that’s practiced privately by millions and millions of people. Nobody actually thinks about it at the big scale—you just concentrate on your feeder in your yard.

Emma Greig, Project FeederWatch leader: There aren’t very many papers on the consequence of feeding birds, but FeederWatch has been thinking about this since the 1970s when the program started. That was the idea: here you’ve got millions of people staring out their window, super invested in the birds that are coming to their backyards already. So the enthusiasm is already there. All you need is to provide a little extra training or guidance to take that enthusiasm and turn it into meaningful data. [Since then, more than 30 studies have been published using FeederWatch data to get at some large-scale questions. Some of the most interesting discoveries are summarized on this 2011 poster and in this 2017 article.]

Is organized feeding of wild birds a relatively recent phenomenon?

Jones: At first, it was pretty much a casual, do-it-yourself activity—tossing out food scraps or leftover grain. Bird feeding at the scale we see now didn’t really take off until the early 1980s when it became possible to go into a pet food or hardware store and buy all these specialized items for feeding wild birds. It was primarily the [cage bird industry starting to] sell to people to feed to wild birds.

Editor’s note: According to Feeding Wild Birds in America, Thoreau was tossing old corn out his back door in the mid-1800s at Walden Pond. Feeding birds became more widespread by the late 1880s, when Florence Merriam Webster published Birds Through an Opera Glass, one of the first popular field guides, and promoted the use of modern bird feeders. By the mid-1890s, bird feeding had spread across most of America, but it wasn’t until the 1980s that bird feeding was commonly practiced year-round.

How big is the bird-feeding industry?

Jones: It’s utterly gigantic. The latest figure I’ve got is that $4 billion a year is spent on feeders and primarily on seed, in the United States alone. It’s probably similar across the whole of Europe. The people I spoke to within the industry say it’s still growing but it is slowing down—which probably means that pretty much anyone who could possibly have a feeder has one now. [According to Feeding Wild Birds in America, the U.S. market for bird feed was $4 billion in 2012, with another $970 million spent on feeders and other accessories.]

Greig: [People get into] bird feeding as they have the time and money to invest in bird feeders and bird seed. So, even if the number of people [right now is] saturated, who those people are is going to be changing. So continuing to spread good messages about how to feed birds safely and how to learn as much as you can from the hobby I think is worthwhile.

Is feeding wild birds a good thing?

Jones: There are many examples of how birds are benefiting from feeding—no question at all that they are more likely to survive winter if they get fed. [Some] species that may be having a hard time, especially in an urban environment, benefit from the food they find in people’s yards.

Greig: Some of the good aspects are that there are studies showing that feeding birds increases survival during particularly harsh conditions. So, in the dead of winter when there’s snow covering everything and it’s super super cold, birds benefit from being able to come to feeders and being able to get some suet or black oil sunflower seeds, something nice and fattening.

But these are species, typically, that are used to having ephemeral food sources. I like to point out that there is no reliable food source for most birds so they’re used to flying around trying to seek food knowing that they can’t ever really count on anything. Birds know how to plan for that. The way to think about feeders is really that it’s a supplement.

One thing that we are noticing in some [feeder] species—it’s a super interesting pattern—is that their ranges are expanding north. We’re seeing this in things like Red-bellied Woodpeckers, Carolina Wrens, Anna’s Hummingbirds. So they’re starting to occur in places they didn’t occur before and they’re moving into colder locations. It’s very possible that supplementary feeding has something to do with that.

What’s the biggest risk from feeding wild birds?

Jones: The most serious issue is the spread of disease. If a bird is infectious, [visiting a feeder is] the ideal way to spread it. But people are not going to stop feeding, nor should they. We need to take the responsibility of having a feeder much more seriously and minimize the risk of spreading disease.

That’s why the book is called The Birds at My Table. If you’re inviting friends over, you want to make sure that everything’s right. Now that we realize the scale and implications of feeding wild birds—it’s not just my own feeder in my own backyard any more—it’s part of a network across the whole landscape, so we have to take responsibility for what we’re doing.

Greig: Some of the potential cons: there are things such as increased transmission of disease because you have animals all coming to one place. Increased threat of predation, again because you have these potential prey items coming to one location, so if you’re a hawk, you may figure out “Ooh that’s where I want to go to get my lunch.” People having pet cats that are hanging out around feeders. Feeding often takes place around houses so there’s this increased potential for birds to hit windows.

So keeping your feeders clean, offering decent food, keeping your cats indoors, putting feeders a safe distance from windows. Those are very simple steps that anyone who feeds birds can take.

Why do people feel so deeply about feeding birds?

Jones: That’s probably the most fascinating [question] of all—it’s so much more complex than I ever imagined. A lot of people feel that we humans have done so much damage to the environment and therefore to birds, that they want to give something back—which is a pretty serious, profound activity. Others just really want to learn about birds and feeding brings them up close. And that leads to this whole area where interacting with nature can lead to increased psychological, physical, and spiritual well-being. If that’s the case, bird feeding is one of the most intimate, immediate kinds of interaction with nature that you can have.

Greig: I suspect that it’s a desire, if not a need, to connect with the outdoors and with nature and with other living creatures. Feeding birds allows people to do that in a really easy way, because they are coming to you. These animals are coming right to your window. Also, when you are contributing your observations to a really large data set, your little observations take on a life of their own. This activity that you love is a part of something bigger.

Should we stop feeding wild birds?

Jones: Not at all. This is a noble activity—we just need to do it with the birds in mind. Most of our motivation is human motivation—we want to feel good about it. That’s fine. As long as we also do it with the birds’ well-being in mind. It would be dreadful if we found out that an activity that we get so much enjoyment out of was actually harming birds in any way, so that’s why we have to utterly minimize the risk of disease. We just have to accept the responsibility for what we’re doing and continue to enjoy it.

Greig: I think on balance, feeding is a good thing. Do it responsibly. Collect some data along the way. The more [people] who are paying attention to what is happening in their yard and doing something like FeederWatch, the better. That’s how we’ll know how things are changing.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library