Where Do Migrants Go in Winter? New Models Provide Exquisite Detail

By Gustave Axelson; Illustrations by Jillian Ditner

January 4, 2021Every year, migratory birds in the North disappear. The next generation of eBird species distribution models shows precisely where they go in greater detail than ever before.

From the Winter 2021 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Part of the magic of migratory birds is their annual disappearing act—one autumn day there might be an oriole in a treetop, and the next day it’s gone, not to be seen again until spring.

Back in the 17th century, scientists had lots of ideas about where birds go during winter in the Northern Hemisphere, including one theory that they migrate to the moon. Today we know Neotropical migratory birds are intercontinental travelers, chasing summer as they leave the North for the warmer weather and longer days of the New World tropics.

Birders in the U.S. and Canada are accustomed to saying that birds spend the winter down south, but because the seasons are reversed on either side of the equator, scientists prefer to use the term nonbreeding season. An ornithologist’s year is comprised of four parts: prebreeding (spring) migration, breeding season, postbreeding (fall) migration, and the nonbreeding season.

But not all parts of a bird’s annual cycle are created equal. A Baltimore Oriole may spend five months from November to March in its nonbreeding-season range, more than twice as long as they live in their breeding range.

Scientists may not believe birds are moon travelers anymore, but for most of the 20th century they had only vague notions of where birds go on migration. In the old printed field guides, range maps showed Baltimore Orioles overwintering anywhere from Mexico to Colombia. For the past 15 years, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s eBird Science team has been hard at work on the next generation of range maps. Through advances in big-data supercomputing, eBird is melding the observations of 120,000 birders with NASA satellite imagery to show precisely where birds go during all four parts of their annual cycle—including a nonbreeding-season map that shows most Baltimore Orioles overwintering in the core of Central America.

These eBird maps hold answers to one of humankind’s age-old questions: Where did the birds go? As it turns out, that oriole could now be at a backyard fruit feeder eating bananas, bringing joy to a family in Costa Rica as it gains strength for the journey back north.

Forest Birds of the North Become Forest Birds of the South

Though Neotropical migratory birds fly thousands of miles south during the nonbreeding season, they are often seeking climatic niches and habitat conditions similar to the places they left up north.

Prothonotary Warbler

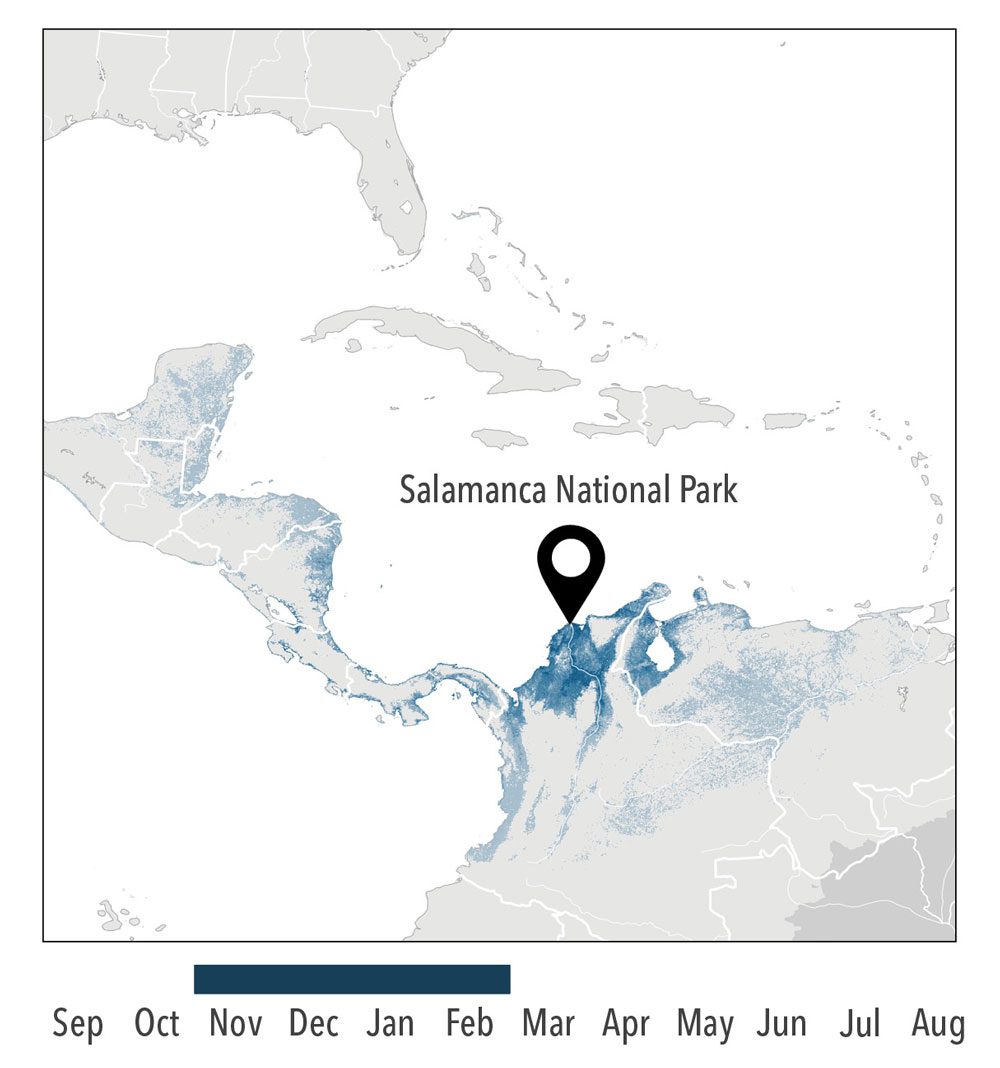

Prothonotary Warblers (Protonotaria citrea) like one kind of habitat—wet forests—and they seek it out wherever they are from the breeding to the nonbreeding seasons, whether flooded woodlands in the southeastern U.S.A. (they’re called “swamp warblers” in Georgia and the Carolinas) or mangroves in Panama and South America.

But these warblers don’t act the same in both places. While conducting field research in mangrove forests and lagoons along Colombia’s Caribbean coast, scientists observed up to 240 prothonotaries gathering together at nocturnal communal roosts. These birds space out on their breeding grounds up north, where males aggressively defend territories and densities can be as low as three warblers per 100 acres. But on their overwintering grounds where they sometimes roost at night, an acre of nonbreeding habitat can contain more than 10 times as many warblers as an acre of breeding habitat.

A prothonotary treasure trove along the Colombian coast

Research using geolocators has shown that Prothonotary Warblers from Virginia, South Carolina, Arkansas, Ohio, and Louisiana fly south to northern Colombia and the Magdalena River Valley for the nonbreeding season. Salamanca National Park, which is filled with coastal mangrove forests, contains the largest known abundance with up to 48,000 overwintering prothonotaries, or 3% of the entire global population in a single spot.

Source: L. Bulluck et al. (2019). Habitat-dependent occupancy and movement in a migrant songbird highlights the importance of mangroves and forested lagoons in Panama and Colombia. Ecology and Evolution.

Yellow Warbler

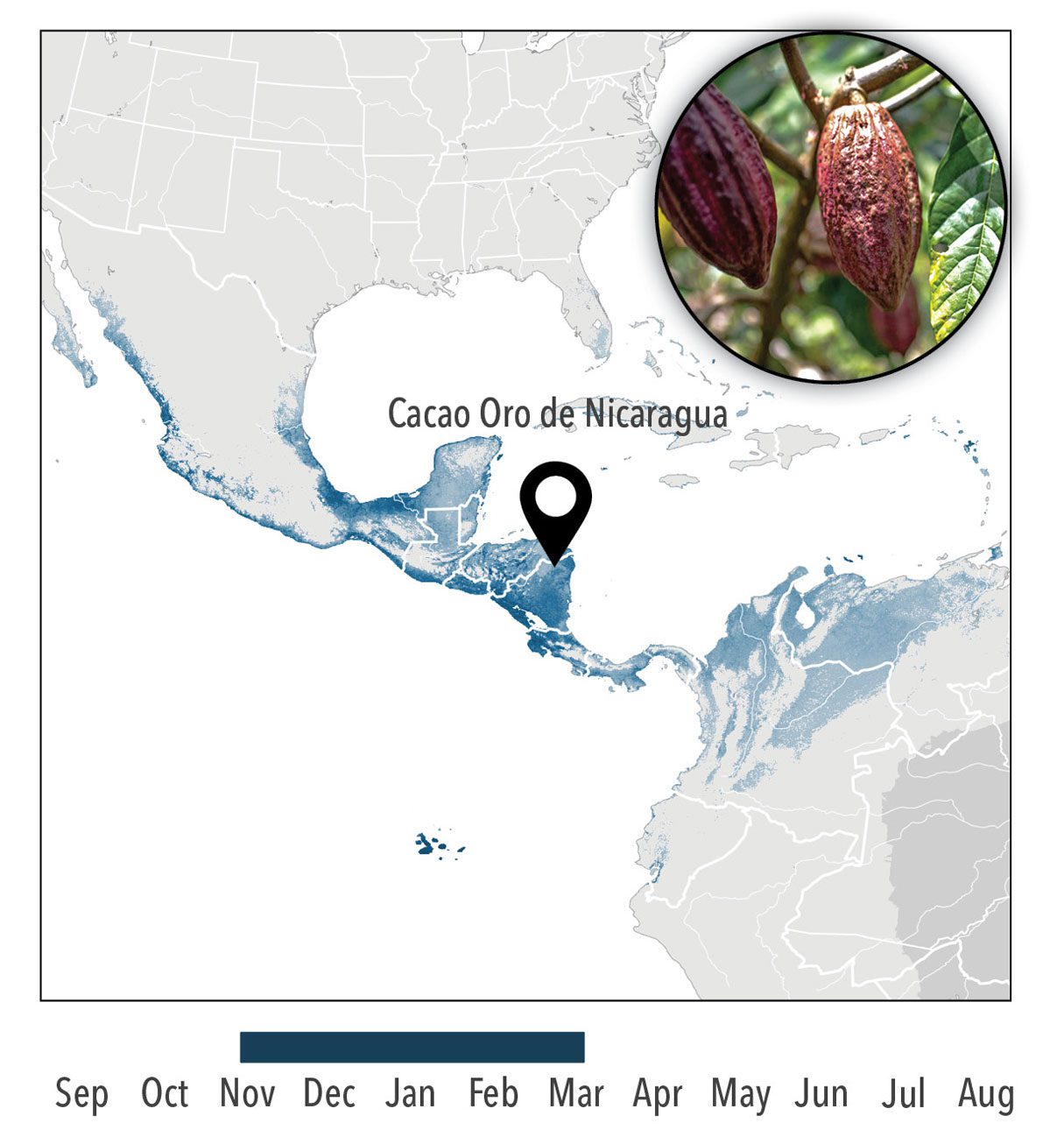

Yellow Warblers (Setophaga petechia) have an expansive breeding range from Alaska to the southern Appalachians. During the nonbreeding season, Yellow Warblers cram into an overwintering range that’s much smaller. eBird data analysis shows that millions of Yellow Warblers—13% of the global population—overwinter in Nicaragua, where they’re often found in shade-coffee farms and other agroforestry operations.

Growing chocolate on farms that also feed warblers

Cacao Oro de Nicaragua is a cocoa plantation in Nicaragua that’s home to tens of thousands of overwintering Yellow Warblers. After the farming lands were devastated by hurricanes, the Cacao Oro farm was founded as a large-scale agroforestry model to rehabilitate more than 3,000 hectares (or almost 7,500 acres). By 2022, Cacao Oro will harvest about 4,000 metric tons of UTZ-certified sustainable cocoa, while restoring forest cover and employing local indigenous workers.

American Redstart

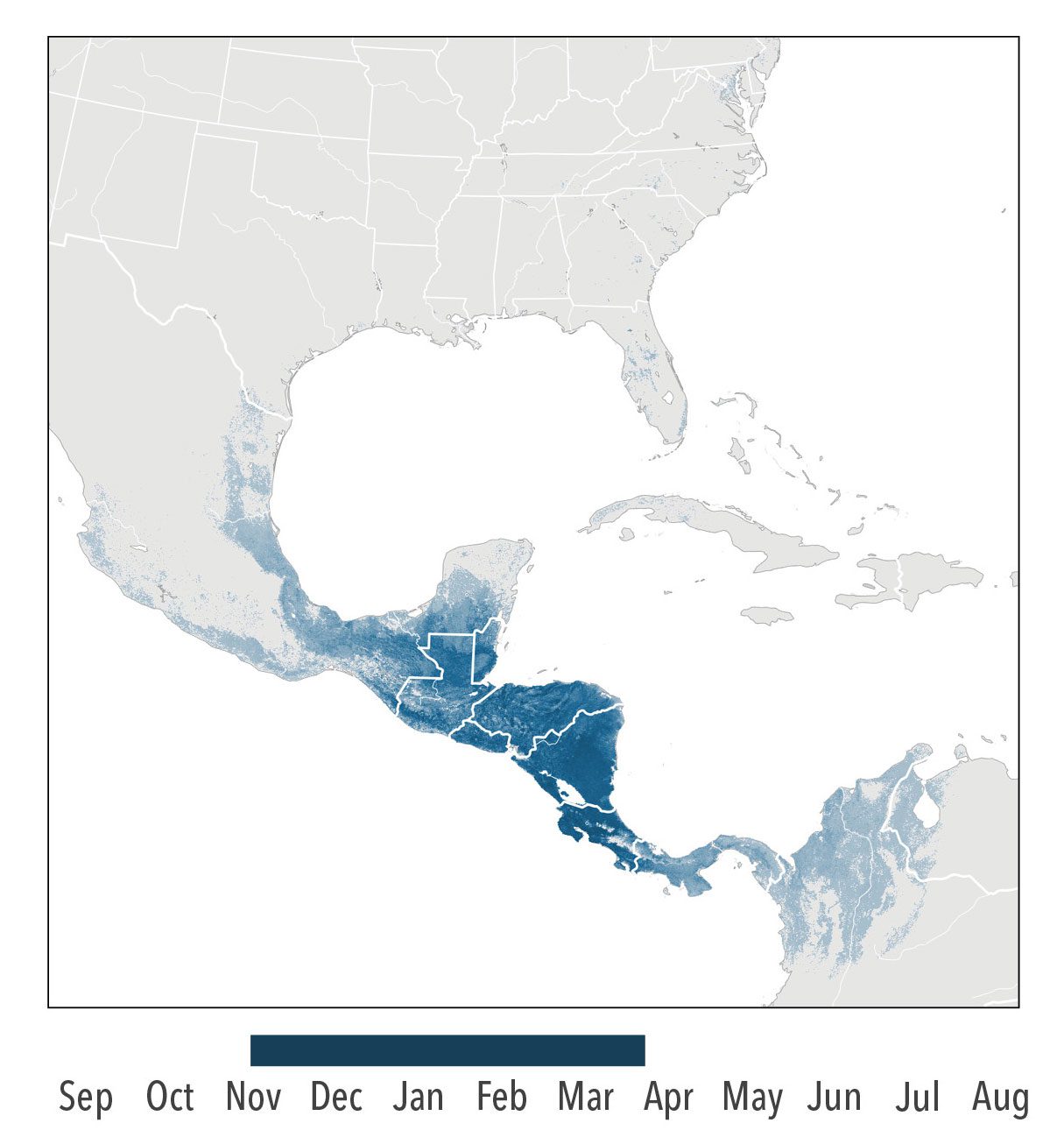

On their fall migration south, hordes of American Redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla) launch themselves off the coasts of Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana to fly across hundreds of miles of open water in the Gulf of Mexico until they find land again on the Yucatan Peninsula. eBird data analysis shows that about a third of the global population of American Redstarts overwinters in the Yucatan regions of Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala.

Warblers among Mayan ruins

The Mayan Forest is the largest tract of forest left in Central America, home to 21 species of migratory warblers from November through March—including one-tenth of the world’s American Redstarts. In 2017, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology partnered with the Mexican government and the Wildlife Conservation Society to launch a community bird-monitoring and conservation project here. The research shows that cleared cattle pastures can be restored to forest and support migratory birds within just a few years.

Blackpoll Warbler

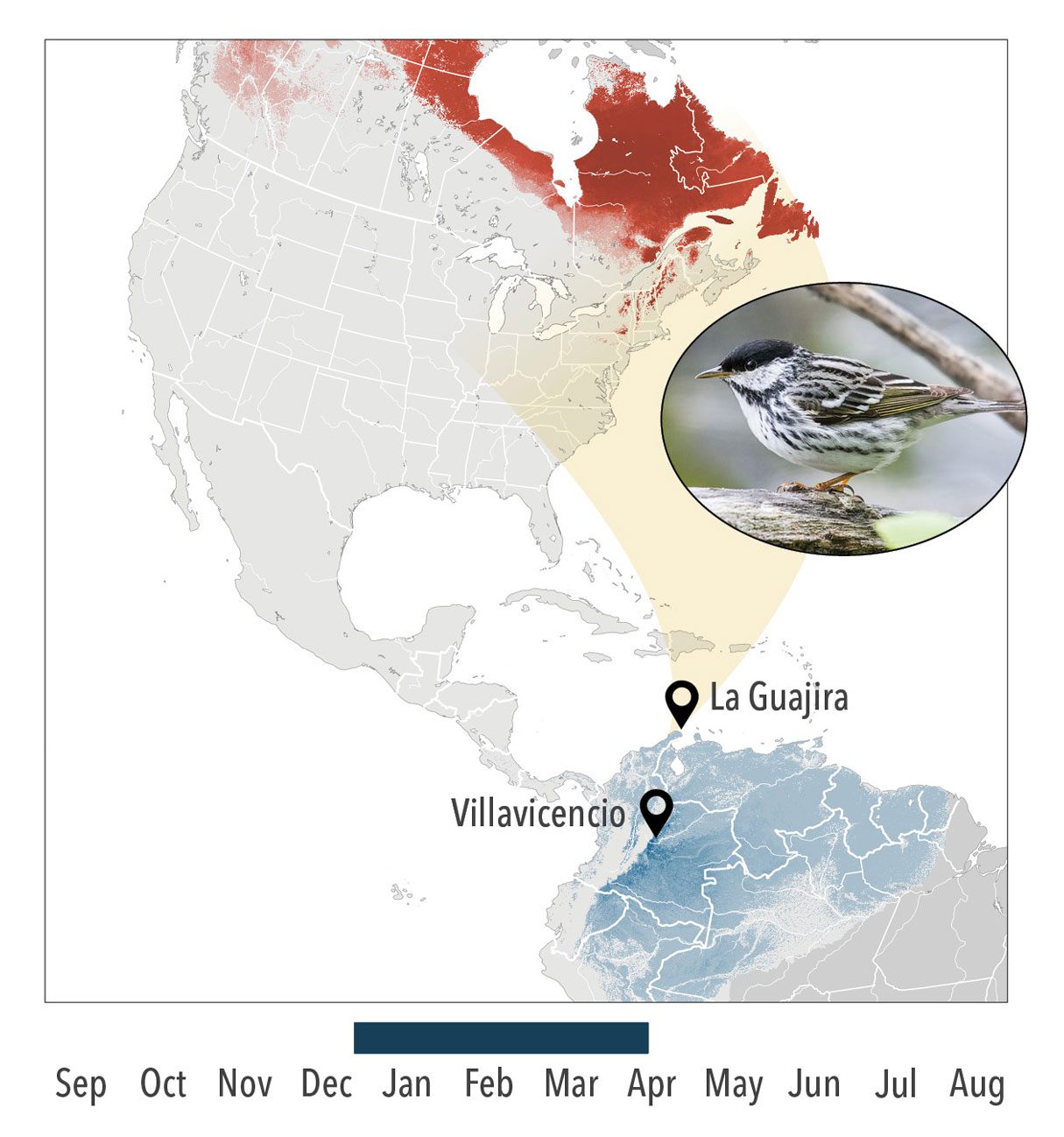

In their annual migrations between northern North America and South America, these long-distance athletes fly more than 20,000 km (or 12,500 miles)—enough to earn a free trip in some airline frequent-flyer programs.

Though Blackpoll Warblers (Setophaga striata) breed all across North America from Alaska to the Canadian Maritimes, they cluster into northern South America for the nonbreeding season. These four months are crucial to each Blackpoll Warbler’s survival, as it’s among the forests of the Andes Mountains and Orinoco and Amazon River basins that they’ll feed and pack on weight to fuel the journey back to their boreal forest breeding grounds.

La Guajira Peninsula on Colombia’s northern coast is the first place many Blackpoll Warblers touch down after an incredible 1,800-mile flight south off the Atlantic Coast. It’s the longest recorded overwater journey of any songbird. When the Blackpolls arrive they’re emaciated, but they quickly fatten back up, growing their body mass by 20% in just a few days by gorging on caterpillars. The timing of the Blackpolls’ arrival is synced with a rainy season in La Guajira, which spawns a furious green-up of trees—and a corresponding profusion of caterpillars. Migration-weary Yellow-billed Cuckoos and Prothonotary and Connecticut Warblers also join in with the Blackpolls to feast on caterpillars.

A warbler fueling station in the foothills of the Andes

Scientists have documented Blackpoll Warblers increasing their body mass by 40% at the end of the nonbreeding season by feeding in the foothills around the city of Villavicencio, a mix of native forests and plantations for citrus fruits and cacao (for chocolate). A study showed that the weight Blackpoll Warblers put on here fueled nonstop northward flights of more than 2,700 km (or 1,600 miles) to Cuba, Florida, even South Carolina—more than half their spring migration back to Canada.

Sources: N. Bayly et al. (2020). There’s no place like home: tropical overwintering sites may have a fundamental role in shaping migratory strategies. Animal Behaviour; C. Gomez et al. (in review). Migratory connectivity then and now. Proceedings of the Royal Society B; N. Bayly and K. Rosenberg. (2020). Discovery of a vital link in the marathon migration of the Blackpoll Warbler. Partners in Flight.

Baltimore Oriole

Orioles are a backyard feeder favorite for North American birders in summer. Set out an orange half and happy orioles will gorge like kids on ice-cream sundaes. Where do the bright-orange birds get their sweet tooths? During the five months of their nonbreeding season in Central and South America, their diet includes foraging on orange and banana trees. So when they get back north to their breeding grounds, the orioles look for their favorite tropical fruits.

On their overwintering grounds in Central America, Baltimore Orioles (Icterus galbula) are common visitors to shade-coffee farms. The orioles arrive just as the coffee berries are turning red. When the farmers see the orange-and-black birds in the trees, they know it’s time to harvest the coffee.

Backyard bird in the North and South

About 55% of the entire population of Baltimore Orioles overwinters in El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, where they are welcome visitors in backyards. In Costa Rica people set out fruit on wooden platforms, and the return of this colorful bird every year signals the coming of the dry season.

Sources: K. Sparrow et al. (2017). Conditions on the Mexican moulting grounds influence feather colour and carotenoids in Bullock’s Orioles. Ecology and Evolution.

Bullock’s Oriole

Baltimore and Bullock’s Orioles used to be considered the same species (called the “Northern Oriole”). But today scientific research has shown that they are two different birds, with Bullock’s Orioles (Icterus bullockii) having a distinct DNA profile and different breeding range in the West.

Like their eastern cousins, Bullock’s Orioles can be seen on coffee farms during their nonbreeding season, though their overwintering range is farther northwest than that of Baltimore Orioles. Bullock’s Orioles were frequently seen during bird surveys on shade-coffee farms in the state of Chiapas in southern Mexico.

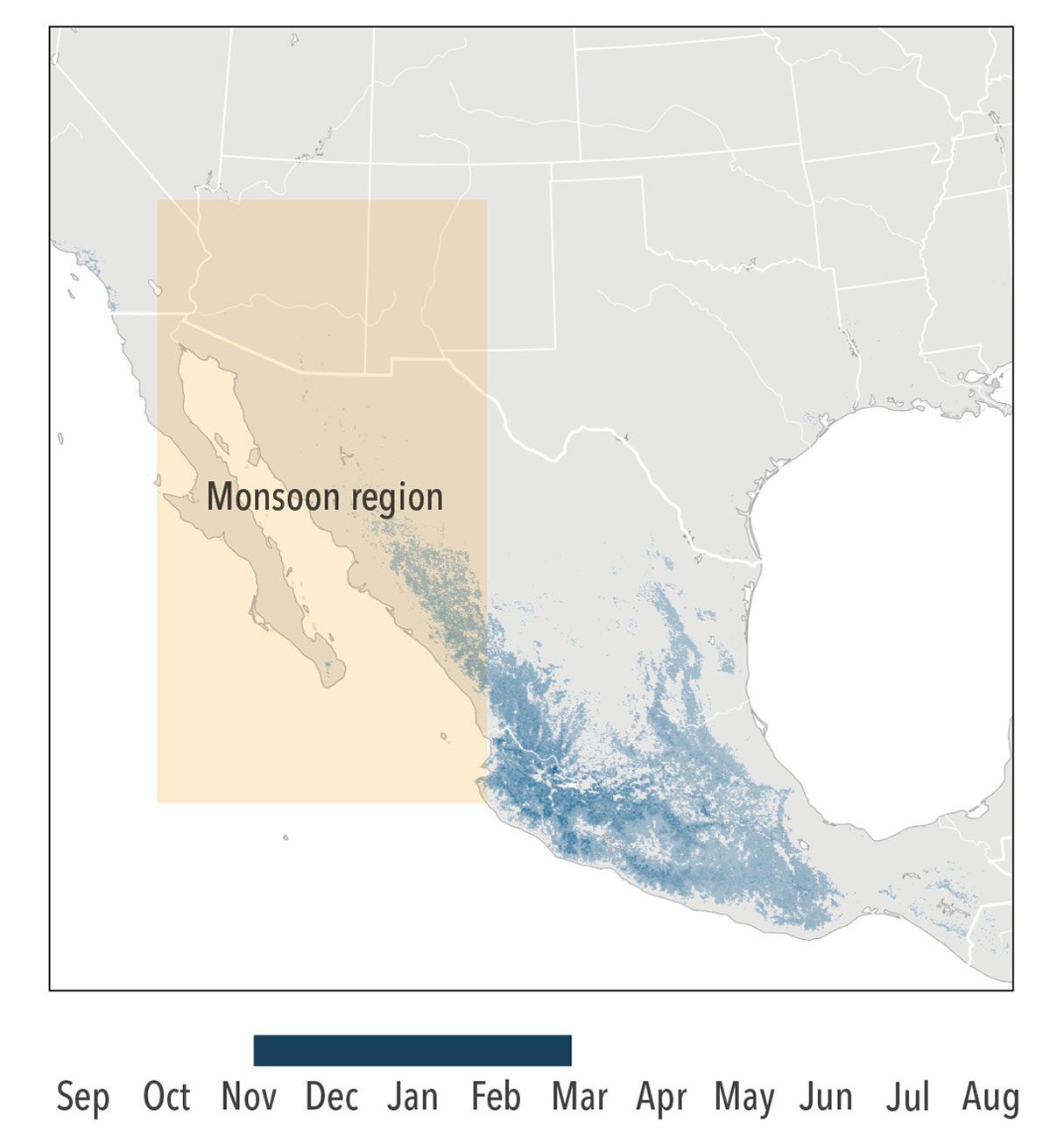

A pit stop for Mexican monsoons makes for brighter feathers

Bullock’s Orioles make a two-part migration south in autumn. First, they stop off along the southwestern U.S. border and northern Mexico to take advantage of the monsoon season. Whereas most songbirds molt on or near their breeding grounds, Bullock’s Orioles grow new feathers during this mid-migration stopover. Recent research has shown that where the orioles settle and what they eat during their molt period in Mexico is directly associated with plumage coloration. It appears that birds with a more plant-based diet (likely eating fruits rich in red or orange carotenoids) are able to produce more colorful plumage. The now-flashier orioles then continue on as far as Guerrero and Oaxaca in southern Mexico for the five months of their nonbreeding season.

Epic Journeys

Raptors and shorebirds make the longest seasonal migrations down the Americas.

Broad-winged Hawk

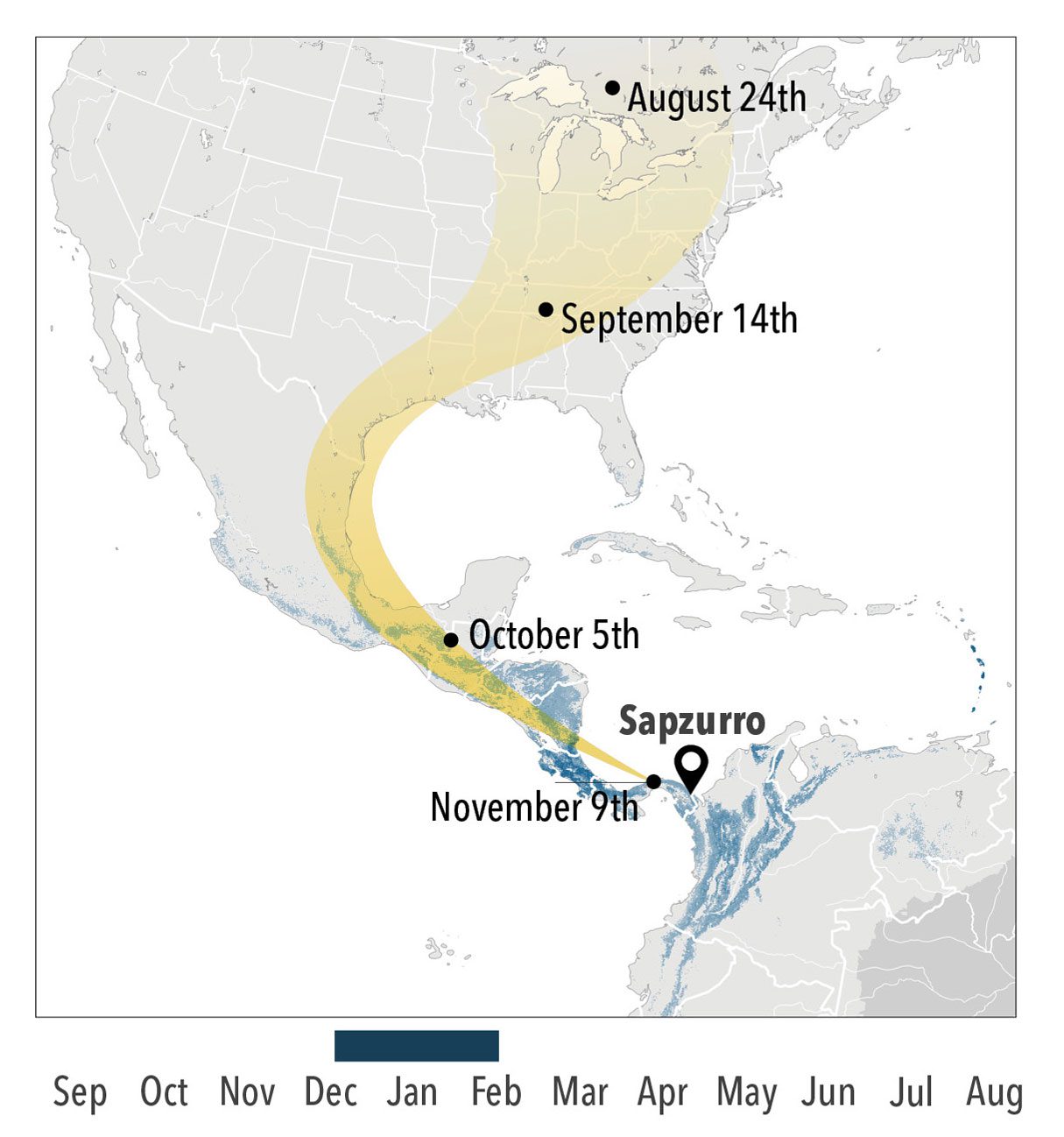

Each fall, spectacular kettles of Broad-winged Hawks (Buteo platypterus) by the hundreds are a prime attraction at hawkwatch sites in Pennsylvania and Minnesota. But their numbers and densities grow even higher as they continue farther south, funneling down the narrowing hourglass landform of Central America and joining with other species to form massive migratory flocks of hawks by the tens of thousands—what’s been called a “river of raptors” flying through Veracruz, Mexico, and Panama.

Scientists have used satellite transmitters to track Broad-winged Hawks as they traveled from Canada all the way down to overwintering grounds in the Andean forests of Colombia and Bolivia—a trip of more than 4,000 miles, completed in increments of about 70 miles per day.

Above a small Colombian fishing village, one of the world’s busiest raptor highways

The little border town of Sapzurro, where Panama meets Colombia, is one of only six places in the world where more than half a million migrating raptors have been counted in a single season. Sapzurro lies near the Darien Gap, so-called because its rugged jungle is the only gap in the Pan-American Highway that runs from Alaska to Chile. The isthmus here is only about 100 miles wide, and according to bird surveys conducted by the nonprofit science group SELVA, almost 140,000 Broad-winged Hawks passed above Sapzurro in the fall of 2012.

Source: N. Bayly et al. (2014). Migration of raptors, swallows and other diurnal migratory birds through the Darien of Colombia. Ornitologia Neotropical.

Broad-winged Hawk, adult plumage by Dan Brown/Macaulay Library.

A kettle of hawks in Sapzurro. Photo by Nick Bayly.

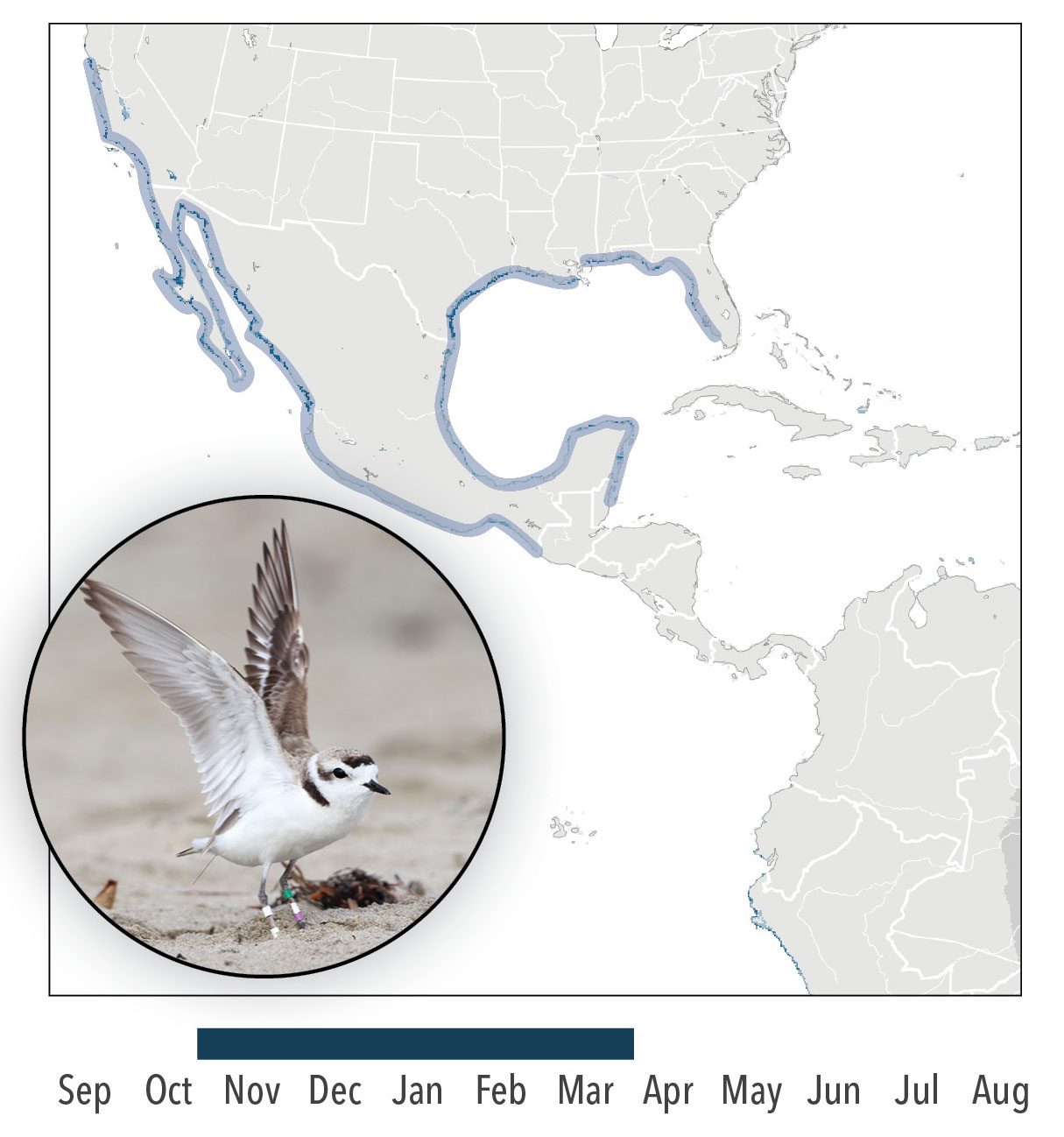

Snowy Plover

Snowy Plover (Charadrius nivosus) breeding populations are scattered along the Pacific and Gulf coasts, with a few inland breeding groups at alkaline or saline lakes and reservoirs. In the nonbreeding season, Snowy Plovers cluster along the coasts of southern California, Texas, and Mexico. The Pacific Coast population of Snowy Plovers is protected under the U.S. Endangered Species Act due to habitat loss along beaches.

Return of the plovers

In the 1990s, Snowy Plovers were extirpated from the beaches around Ensenada, Mexico, on the Baja Peninsula. Mexican biologist Jonathan Vargas started a program in 2017 to bring the Snowy Plovers back. In 2019, Vargas joined the Cornell Lab’s Coastal Solutions Fellows program and worked with local conservation groups to convince the city council to implement policy regulations that protect shorebird habitat. With fencing installed around plover areas on the beaches and teams of people keeping watch against ATVs and disturbance, the Snowy Plovers returned. In the last two years, more than 50 plover nests have hatched more than 150 chicks. More than 80 banded plovers from southern California have been documented overwintering there.

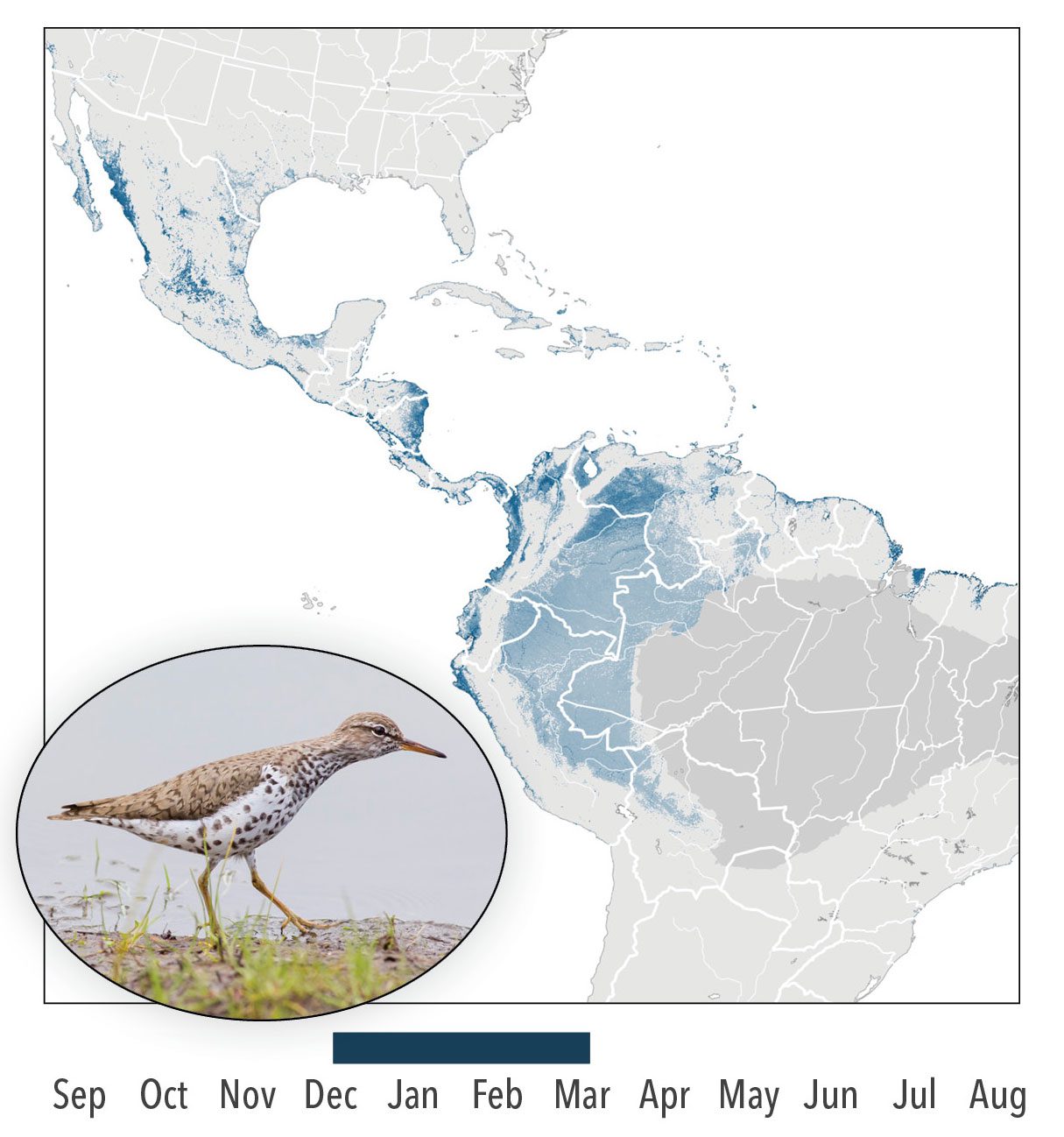

Spotted Sandpiper

The dapper Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularius) is a common bird in both hemispheres. It’s the most widespread breeding sandpiper in North America, and one of the most wide-ranging overwintering shorebirds in South America, from coastal beaches and mangroves to the Amazon Forest interior.

Sandpipers on the Amazon

The best time to count birds in South America is August to April, as that’s when breeding birds there are singing and migratory birds from North America have taken up residence for their nonbreeding seasons. Ken Rosenberg, a Cornell Lab conservation scientist, says Spotted Sandpipers were common birds during his survey expeditions deep into Peruvian rainforests. “Traveling by boat through the remotest tributaries of the Amazon River, Spotted Sandpipers were a familiar sight,” says Rosenberg. “We flushed Spotted Sandpipers along the sandy riverbanks at every bend in the river.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library