Tracking 3 Jaeger Species Across 4 Oceans—and Into a Comic Book

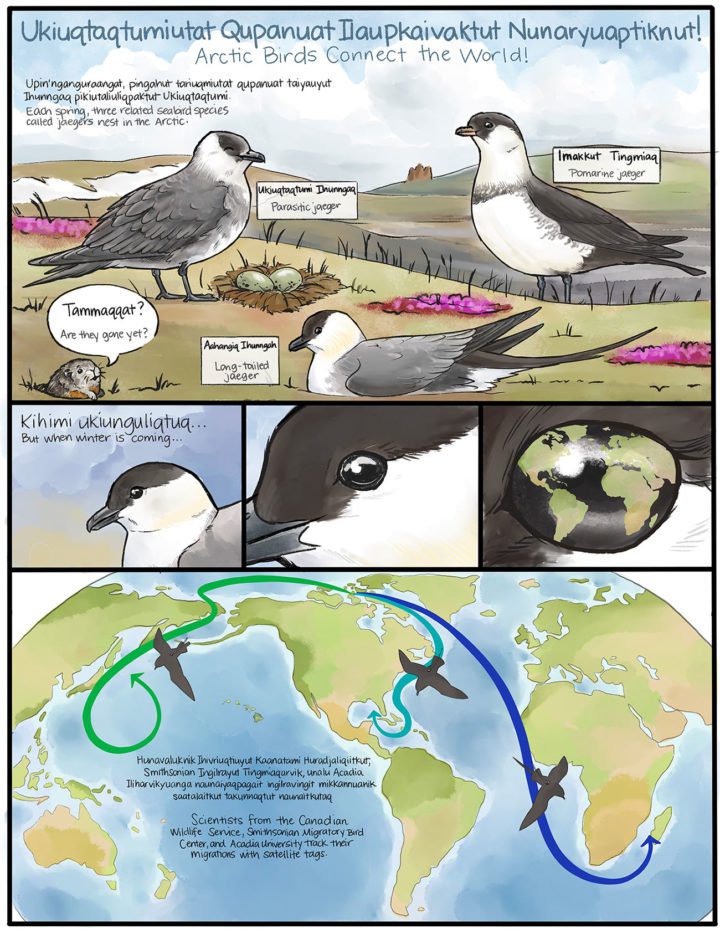

Jaegers nest in the Arctic and then fan out across the open ocean to spend winters stealing food from other seabirds. But until scientists with miniature satellite trackers got involved (along with one gifted comic artist), nobody had any idea just how far the intrepid birds traveled.

By Abby McBride

March 24, 2022

From the Spring 2022 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

It’s spring on the Canadian tundra at Nanuit Itillinga National Wildlife Area, and three kinds of jaegers appear out of nowhere, ready to start nesting.

Where in the world have these transoceanic-traveling seabirds been all year? Until recently, their movements were a mystery. But research published in the journal Ecology and Evolution in December 2021 revealed some answers from this High Arctic location in Nunavut where Pomarine, Parasitic, and Long-tailed Jaegers all come to breed.

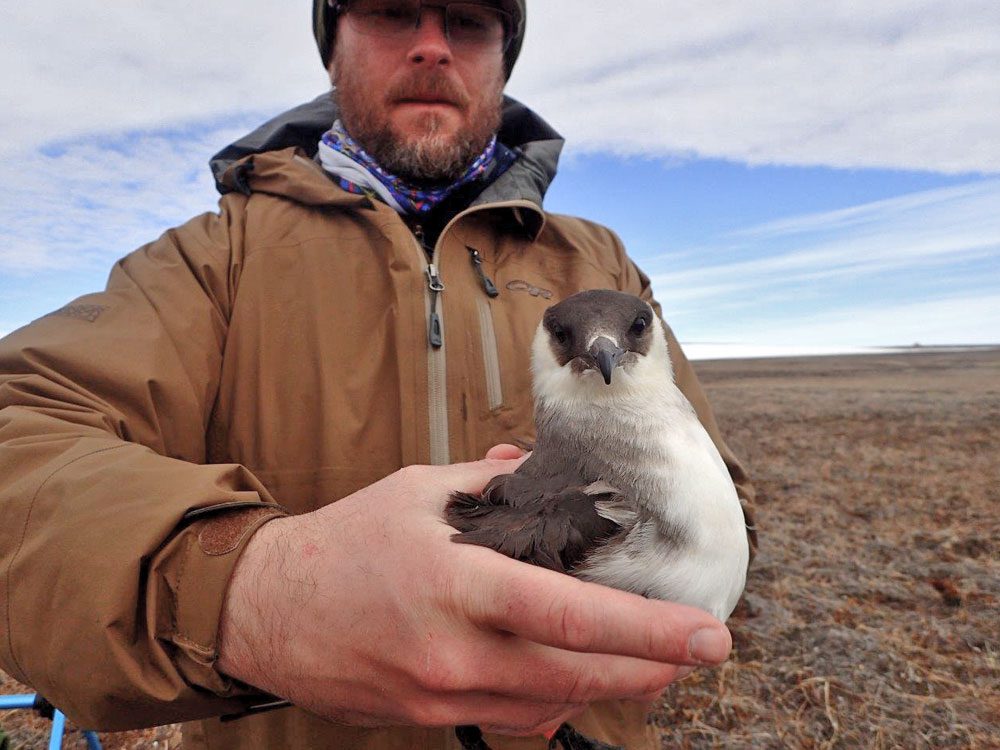

Jaegers are circumpolar breeders and these three species likely overlap at many nesting locations. But this spot is near a High Arctic science field station operated by the Canadian government, which provided Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center research scientist Autumn-Lynn Harrison with a ready base of operations for jaeger research. In the springs of 2018 and 2019, Harrison worked with the Canadian Wildlife Service to capture adults of each jaeger species at the nest and tag them with satellite transmitters. Watching the data stream in, her team discovered that the three jaegers spread out on three vastly different migratory journeys across four oceans.

“Jaegers aren’t the most appreciated birds in the Arctic,” says Autumn-Lynn Harrison, “[but] they are such beautiful birds on the wing. It’s hard not to fall in love with them.” Long-tailed Jaeger by Ian Davies/Macaulay Library.

A dark-morph Parasitic Jaeger. This bird was fitted with a satellite tag, about the same weight as two nickels. Photo courtesy of Don Cecile.

A Pomarine Jaeger—biggest, most formidable, and most enigmatic of the three jaeger species. Photo by Brian Sullivan/Macaulay Library.

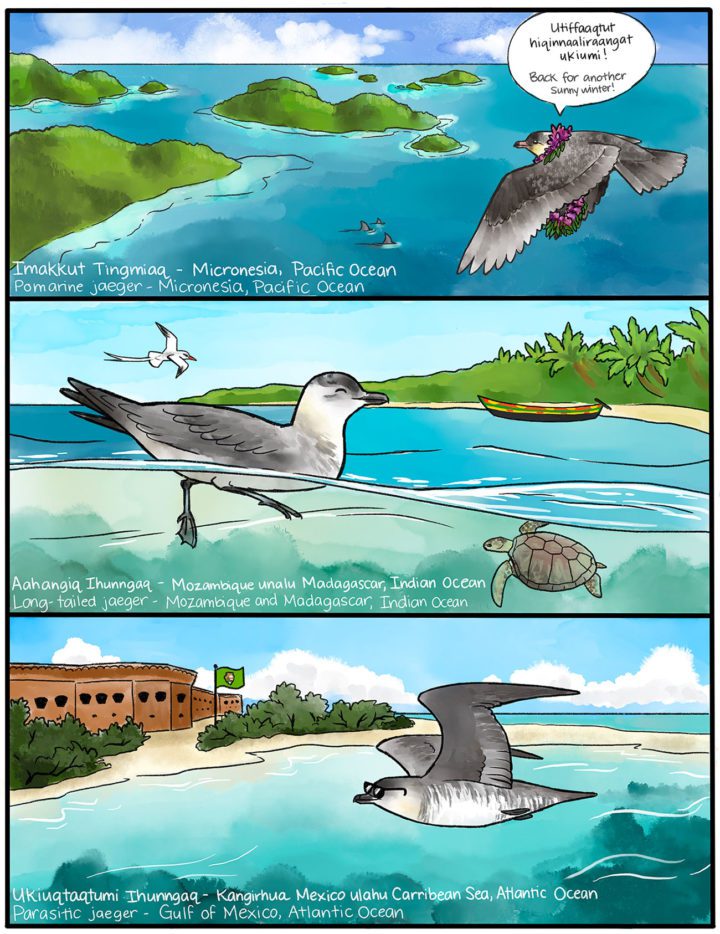

Communicating Science through Comics. When their jaeger research was accepted for publication, study authors Autumn-Lynn Harrison and Jennie Rausch decided to go beyond issuing a press release—they partnered with artist Laurel Mundy, whose charming comic-book illustration style could help give the jaegers an image makeover.

The comic was produced in five languages—the Arctic indigenous languages of Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun, along with English, French, and Spanish—so it could reach people across multiple continents within the expansive ranges of these roaming birds.

In addition to being released online, the “Arctic Birds Connect the World” comic will be printed and distributed to schools in Nunavut, as well as published in a full-length comic book to be distributed at the opening of the renovated Bird House at the Smithsonian National Zoo in fall 2022. Download the comic here.

Jäger is German for hunter, an apt name for these sleek gull-like birds when they’re on their breeding grounds, chasing down rodents and shorebirds. But for the rest of the year, jaegers are kleptoparasites of the high seas, stealing food from other seabirds to make their living. Jaegers have sprawling winter ranges across multiple oceans, so it was not at all obvious where they would go when they departed Nunavut.

“From the central High Arctic of North America, it’s energetically feasible that all three species could migrate west or east,” said Harrison. Based on previous tracking studies, she guessed that all the birds would head to the Atlantic Ocean.

According to the satellite-tracking data, two Long-tailed Jaegers set off east and went all the way across the Atlantic toward the west coast of Africa, with one of them continuing onward and curling around Cape Horn into the Indian Ocean. Two of their powerful, slightly larger cousins—the Parasitic Jaegers—began on the same eastward trajectory but split off and headed south along the east coast of North America, into the southern Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico.

And a single formidable Pomarine Jaeger—biggest and most enigmatic of the three species—threw a curveball by setting off in the opposite direction, west across the Arctic Ocean and into the Pacific toward Japan and Micronesia. It then roamed over the western North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, a nutrient-deficient area of the ocean that’s home to the infamous Western Pacific garbage patch.

“[This] was truly a surprise,” said Harrison, “and I’m going to take a closer look.”

Scientists in the jaeger migration study worked out of a science station in the High Arctic operated by the Canadian government. Here, a scientist holds a Parasitic Jaeger shortly before banding. Image courtesy Don Cecile.

Banding a Pomarine Jaeger on a remote landscape. Photo by Joel Edwards.

A Parasitic Jaeger being fitted with a satellite tag. Photo by Don Cecile.

The tags can operate for many months, revealing where these oceanic wanderers go when they leave their breeding grounds. Image courtesy Don Cecile.

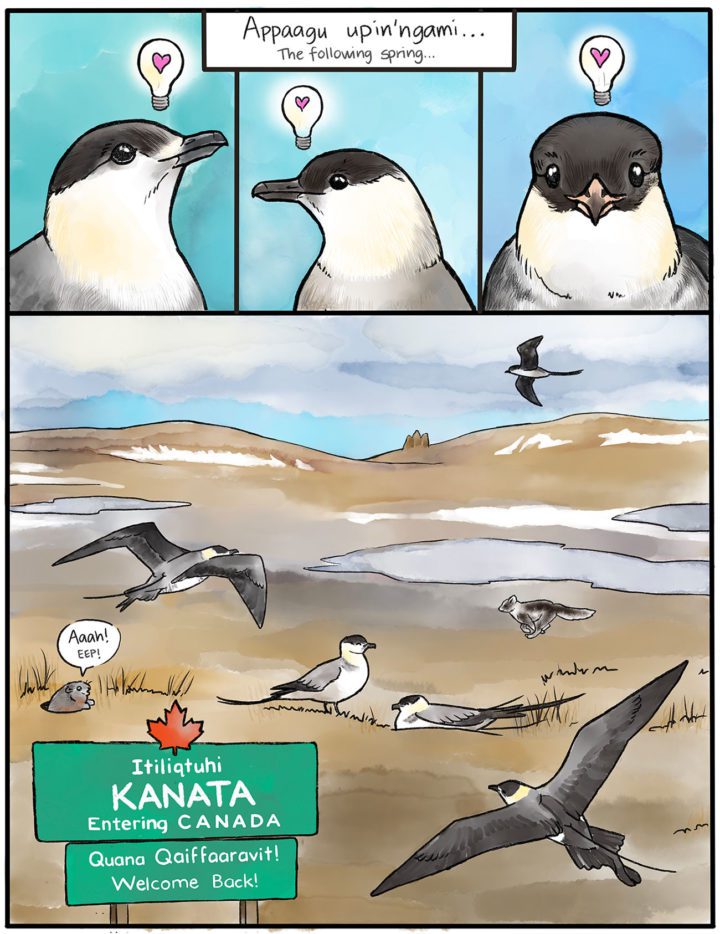

The following spring, when it came time to breed again, the smaller two jaeger species hurried back across the Atlantic and set up territories in Nunavut. Known for being faithful to their nest sites—a trait common to many seabird species—the Long-tailed and Parasitic Jaegers took slightly different routes on their return journeys but ended up right where they had started the previous year.

Not so the Pomarine Jaeger, a species known for its picky eating habits. Pomarines specialize on the brown lemmings whose populations boom and bust erratically around the Arctic. The elusive species has long been thought to breed nomadically, roaming in search of lemmings before choosing a place to nest.

“But before our study, there had never been a Pomarine Jaeger tracked through that period,” Harrison said.

As it turned out, the Pomarine Jaeger tagged by Harrison’s team went on a remarkable ramble. Instead of returning to Nunavut in the spring, the jaeger made a 157-mile overland journey across the Chukchi Peninsula of eastern Russia. Then it struck off west, “really, really far” along the north Siberia coast, Harrison said.

When it finally turned around and recrossed the Arctic Ocean to Canada, the wandering Pomarine went to Banks Island—more than 400 miles away from its breeding site the previous year. (Several days after it arrived, the transmitter stopped working.)

“I was really excited to see that track, and to see that they are really prospecting a huge area before they might settle somewhere,” said Dutch ecologist and jaeger expert Rob van Bemmelen, who spent his PhD years tracking jaegers from field sites in northern Norway and Sweden.

“We just had no idea how nomadic this bird was going to be, both over ocean and over land,” Harrison said. “There’s no way to follow that bird through that whole journey. So that’s what the satellite tag gives us.”

As of late January 2022, one of the jaegers from Nanuit Itillinga wearing a satellite-tag backpack—a Long-tailed Jaeger—was still transmitting a signal in its third year of tracking. The bird was last tracked flying off the coast of Africa from Mauritania to the Cape Verde islands, which “it hasn’t done before,” said Harrison.

Just the latest finding in a study full of new insights.

“We ended up with this really amazing story from just a few individuals,” Harrison said. “It’s just the beginning. We have a lot of future work planned, and it’s just been so special and exciting to get to still do discovery science.”

Abby McBride is a sketch biologist and science writer from Maine. She recently spent a year writing and illustrating stories about seabirds as a Fulbright–National Geographic Storytelling Fellow in New Zealand.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library