Tongass: Birding the World’s Largest Temperate Rainforest

Story and photographs by Tim Gallagher

January 15, 2011

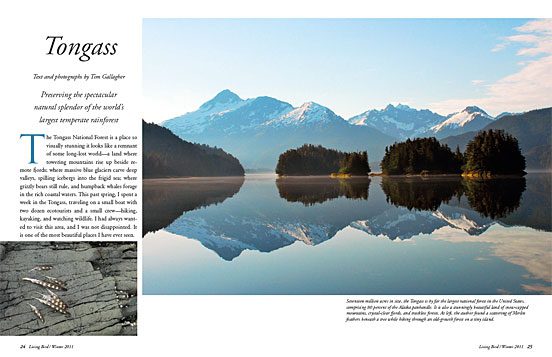

The Tongass National Forest is a place so visually stunning it looks like a remnant of some long-lost world—a land where towering mountains rise up beside remote fjords; where massive blue glaciers carve deep valleys, spilling icebergs into the frigid sea; where grizzly bears still rule, and humpback whales forage in the rich coastal waters. This past spring, I spent a week in the Tongass, traveling on a small boat with two dozen ecotourists and a small crew—hiking, kayaking, and watching wildlife. I had always wanted to visit this area, and I was not disappointed. It is one of the most beautiful places I have ever seen.

At 17 million acres in size, the Tongass is by far the largest national forest in the United States. It comprises the bulk of Alaska’s panhandle—the long, slender southeasternmost stretch of Alaska extending down the northwest edge of British Columbia. Set aside by Theodore Roosevelt through a presidential proclamation in 1902, it was originally called the Alexander Archipelago Forest Reserve but was renamed the Tongass National Forest in 1907. It has since been expanded several times and now comprises about 80 percent of the state’s panhandle. The area was named after the Tongass group of the native Tlingits, who traditionally lived near Ketchikan, in the southern part of the panhandle. Some 75,000 people live in the Tongass National Forest—most of them in cities such as Juneau (Alaska’s state capital), Sitka, and several other communities—but the vast majority is a wilderness where eagles, bears, wolves, whales, sea lions, and other wildlife abound.

The Tongass contains the northern section of the famed Inside Passage—a nearly 1,000-mile-long sea route where vessels can travel from the Puget Sound area all the way along the British Columbia coast to the northern part of the Alaska panhandle at Skagway in relatively calm waters, protected from the open sea by numerous islands. Not surprisingly, it is a popular destination. About a million people visit the Tongass each year, mostly traveling on cruise ships, some of which carry several thousand passengers.

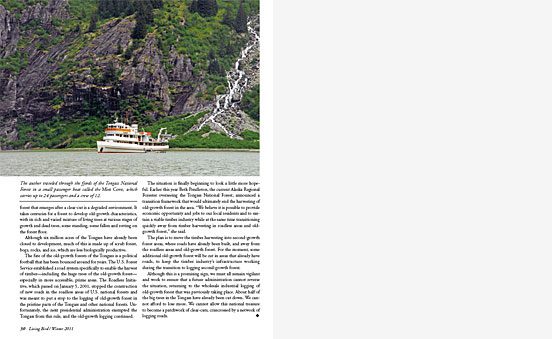

I was more interested in traveling in a way that would have less impact on the environment and provide a more intimate experience than a cruise ship, so I opted to take a small-boat voyage with The Boat Company—a nonprofit educational organization that runs two small passenger boats (one 145 feet long, the other 157 feet long) on weeklong ecotours through the Tongass. (For more information, call toll-free 877-647-8268 or visit their website.) Each boat accommodates only 24 passengers and 12 crew members, so it was easy to anchor in quiet coves each night—where larger vessels are not even allowed—and use the boat as a base from which to go kayaking or to hike on the islands.

Being a lifelong, dyed-in-the-wool bird fanatic, I went to the Tongass hoping to see a lot of fascinating birdlife, but the other animals proved to be just as interesting as the birds. The call would go up from passengers and crew instantly whenever a whale spouted or some porpoises came alongside, bounding out of the water, and we’d all spill out onto the deck, scrambling to get a good view of whatever was out there—humpback whales, Steller’s sea lions, a grizzly bear foraging along the shore of a remote island, or perhaps a distant group of mountain goats, appearing as tiny white dots on a lofty alpine meadow. I was never disappointed, whether the object of interest was a bird, a land animal, a marine mammal, or the spectacular scenery, which was everywhere. Of course, there were plenty of birds. Bald Eagles were especially abundant. We watched them soaring majestically above us, foraging along a lonely beach, or sometimes just perched in some dark green spruces, their brilliant white heads gleaming from miles away. We also saw plenty of Pigeon Guillemots, Tufted Puffins, and Cassin’s Auklets, as well as Marbled Murrelets, which nest in the massive ancient trees of the old-growth forests.

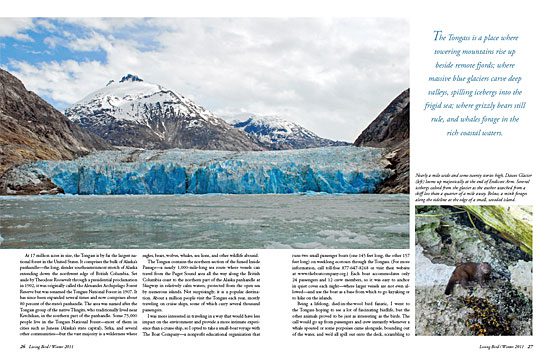

One thing I had hoped to accomplish on this trip was to locate a nesting pair of “Black” Merlins (Falco columbarius sukleyi)—the dark northern race of this tiny falcon, which breeds only in the Pacific Northwest. I have found the nests of two other races of North American Merlins as well as European Merlin nests in Britain and Iceland, so I had high hopes. Alas, although I did walk across several small islands searching for the birds and listening for their distinctive calls, I failed to find a nest. The only trace of a Merlin I found was a few scattered flight feathers amid a pile of waterfowl feathers at the base of a tree, probably a favorite feeding perch of a Peregrine Falcon or other raptor.

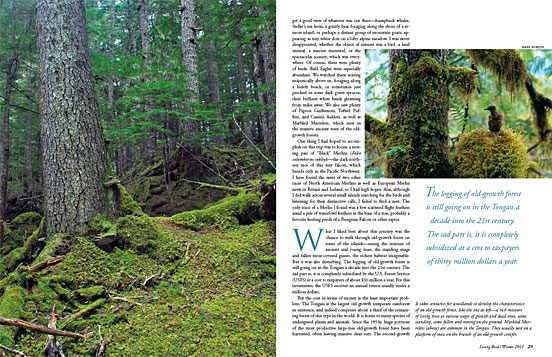

What I liked best about this journey was the chance to walk through old-growth forest on some of the islands—seeing the mixture of ancient and young trees, the standing snags and fallen moss-covered giants, the richest habitat imaginable. But it was also disturbing. The logging of old-growth forest is still going on in the Tongass a decade into the 21st century. The sad part is, it is completely subsidized by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) at a cost to taxpayers of about $30 million a year. For this investment, the USFS receives an annual return usually under a million dollars.

But the cost in terms of money is the least important problem. The Tongass is the largest old-growth temperate rainforest in existence, and indeed comprises about a third of the remaining forest of this type in the world. It is home to many species of endangered plants and animals. Since the 1950s, huge portions of the most productive large-tree old-growth forest have been harvested, often leaving massive clear-cuts. The second-growth forest that emerges after a clear-cut is a degraded environment. It takes centuries for a forest to develop old-growth characteristics, with its rich and varied mixture of living trees at various stages of growth and dead trees, some standing, some fallen and rotting on the forest floor.

Although six million acres of the Tongass have already been closed to development, much of this is made up of scrub forest, bogs, rocks, and ice, which are less biologically productive.

The fate of the old-growth forests of the Tongass is a political football that has been bounced around for years. The U.S. Forest Service established a road system specifically to enable the harvest of timber—including the huge trees of the old-growth forest—especially in more accessible, prime areas. The Roadless Initiative, which passed on January 5, 2001, stopped the construction of new roads in the roadless areas of U.S. national forests and was meant to put a stop to the logging of old-growth forest in the pristine parts of the Tongass and other national forests. Unfortunately, the next presidential administration exempted the Tongass from this rule, and the old-growth logging continued.

The situation is finally beginning to look a little more hopeful. Earlier this year Beth Pendleton, the current Alaska Regional Forester overseeing the Tongass National Forest, announced a transition framework that would ultimately end the harvesting of old-growth forest in the area. “We believe it is possible to provide economic opportunity and jobs to our local residents and to sustain a viable timber industry while at the same time transitioning quickly away from timber harvesting in roadless areas and old-growth forest,” she said.

The plan is to move the timber harvesting into second-growth forest areas, where roads have already been built, and away from the roadless areas and old-growth forest. For the moment, some additional old-growth forest will be cut in areas that already have roads, to keep the timber industry’s infrastructure working during the transition to logging second-growth forest.

Although this is a promising sign, we must all remain vigilant and work to ensure that a future administration cannot reverse the situation, returning to the wholesale industrial logging of old-growth forest that was previously taking place. About half of the big trees in the Tongass have already been cut down. We cannot afford to lose more. We cannot allow this national treasure to become a patchwork of clear-cuts, crisscrossed by a network of logging roads.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library