The Tide is Turning for Shorebirds of China’s Yellow Sea

By Wendy Paulson

April 2, 2021

From the Spring 2021 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Friends often are skeptical when my husband Hank and I tell them that some of our most extraordinary birding experiences have taken place on the coast of China. For sheer volume, diversity, and drama, nothing can top the days we spent on the coast of the Yellow Sea.

On the shores of the Tiaozini mudflat in November 2017, I wrote in my journal about what I regarded as “one of the great wildlife spectacles in the entire world. The sheer numbers, the black ribbons of movement across the sky, the constant repositioning of groups on the mudflats—it made for an avian panorama in perpetual motion.” It was there I had the nearly indescribable thrill of first seeing an exceedingly rare Spoon-billed Sandpiper, pointed out to me by a top-notch Chinese bird guide, then actually finding one myself.

But the reason for the coastal visit was not simply personal interest or adding to a bird list. The birds at the heart of the experience were in trouble. We wanted to see if—and how—we might contribute toward the efforts to protect their rapidly disappearing stopover habitat.

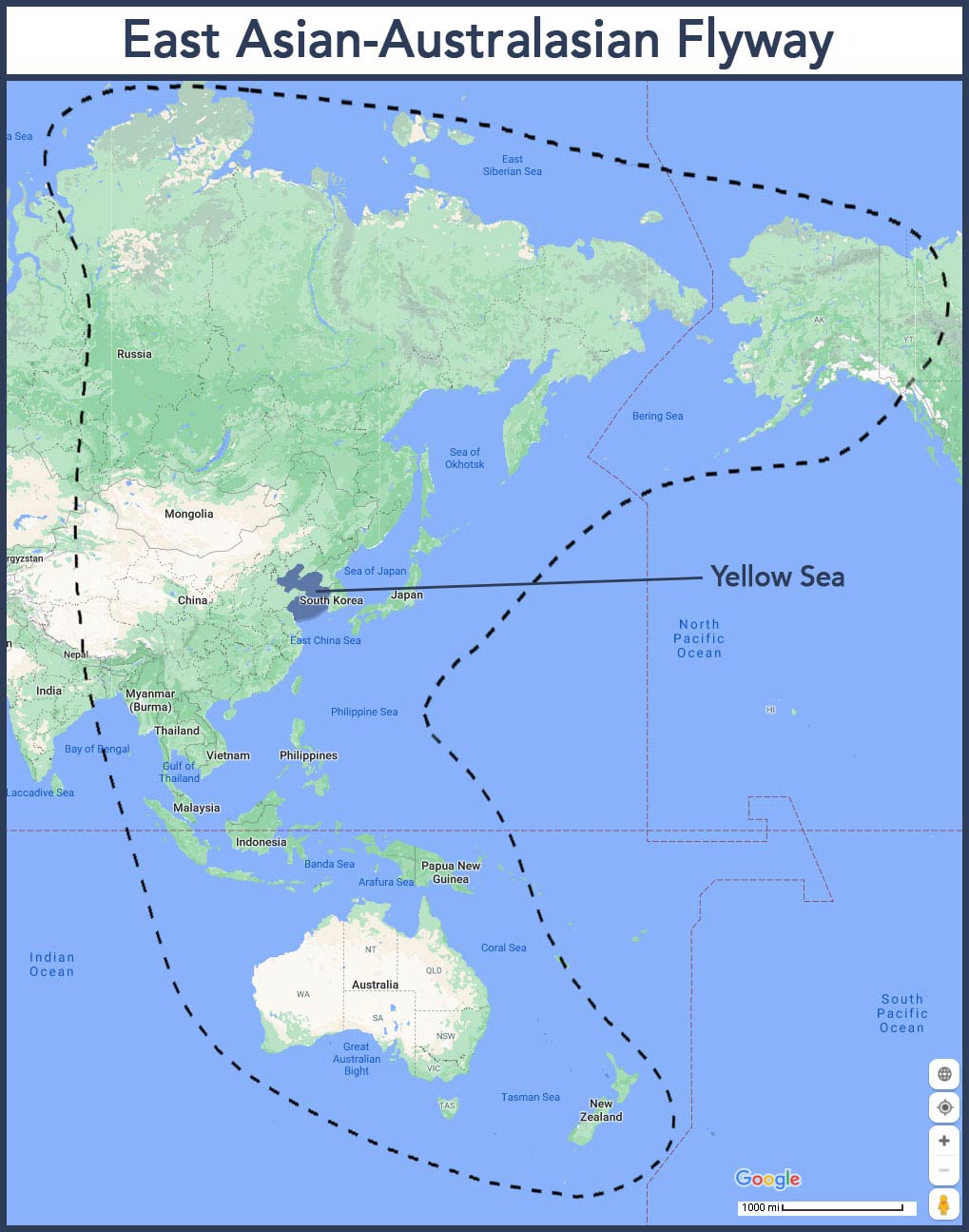

Years earlier during a dinner-table conversation among a group of conservation leaders, Cornell Lab of Ornithology director John Fitzpatrick was asked about the most threatened bird populations in the world, and he answered without pause: the shorebirds of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway. The flyway spans 22 countries from Alaska in the U.S. and Siberia in Russia south through China, southeast Asia, on to Australia and New Zealand. At its heart is the Yellow Sea and Bohai Gulf, a vital service station for 240 waterbird species, including 22 globally threatened species on the IUCN Red List.

The pace and extent of coastal wetland reclamation along China’s east coast was relentless and seemingly unstoppable. Up to 53% of temperate intertidal mudflats, 73% of mangroves, and 80% of coral reefs have been lost in the past 50 years. The flyway was on the brink of collapse. When professor Theunis Piersma, a world-renowned shorebird scientist from the Netherlands, first visited the Bohai Gulf in China in 2010 and looked out at the heavy machinery, dredges, and pumps that were transforming intertidal mudflats into commercial real estate, he lamented: “So this is the end of a flyway.”

The Cornell Lab’s Fitzpatrick clearly hoped that that was not the case. So did we. A collaboration among the Paulson Institute—a “think and do tank” dedicated to U.S.-China relations, with an emphasis on economics, markets, and environmental protection—the Cornell Lab, BirdLife International, and other partners began to grow, with a focus on conservation of key stopover sites in the Yellow Sea.

Critical to the effort were Chinese partners. Chinese scientists had been documenting the numbers and varieties of shorebirds using coastal wetland sites. Through tracking studies, they had been able to prove that what was happening in the Yellow Sea and Bohai Gulf was the root cause of the precipitous declines in shorebird populations. For example, the Far Eastern Curlew has declined by 80% in the last 30 years, the Great Knot by 58%. Most alarmingly of all, the charismatic Spoon-billed Sandpiper has an estimated global population of fewer than 600 individuals, and is falling by an estimated 10% per year.

To build on the science, the Paulson Institute partnered with the Chinese Academy of Sciences to develop a Blueprint of Coastal Wetland Conservation and Management in China. The blueprint concluded that China’s coastal wetlands provided ecosystem services with a value of US$200 billion per year. It identified 180 priority sites for conservation, including 11 of the most critical, but unprotected, coastal habitats for migratory waterbirds. And it proposed a comprehensive set of policy recommendations to strengthen coastal wetland conservation, including the halt of further wetland reclamation.

In the last 30 years, Great Knot numbers have fallen by 58%. Photo by Lefei Han/Macaulay Library.

There are only about 600 Spoon-billed Sandpipers left, and that number is falling. Photo by Lefei Han/Macaulay Library.

Encouraging news came in January 2018, when the Chinese State Oceanic Administration announced a moratorium on all “commercial-related” coastal wetland reclamation along its coastline. The moratorium was reinforced by a policy directive issued by the State Council, China’s cabinet, in July of that year. The speed and strength of the government’s commitment were impressive.

Then the focus quickly switched toward securing long-term protection for the remaining coastal wetlands. The vision was ambitious: to secure World Heritage status for a series of sites along the Yellow Sea–Bohai Gulf. Thanks to hard work by the Chinese government, academics, and nonprofits, and support by the international community, the most important sites—Yancheng Yellow Sea Coastal Wetlands (including Tiaozini) in Jiangsu Province—secured World Heritage status in July 2019. Another 12 sites are due to be nominated for inscription in the coming two to three years. With World Heritage status come hard protection commitments; already, sustainable management and restoration plans are being drawn up at Yancheng.

Far Eastern Curlew populations have declined by 80% in the last 30 years. Photo by Xiwen Chen/Macaulay Library.

Almost all of the Bar-tailed Godwits that breed in Alaska rely on the mudflats of China’s Yalu Estuary during migration. Photo by Brian Calk/Macaulay Library

Of course, securing the long-term future of the world’s most threatened flyway will only be possible if there is cooperation among all 22 countries along the route that share the responsibility to protect the birds and the habitats they need. China’s commitment to safeguard the heart of the flyway is a welcome boost. And more widely, the progress in China should inspire other countries.

More About the Yellow Sea and Shorebird Bird Declines

It is not just birds that will prosper. Coastal wetlands serve multiple, vital functions. They act as buffers to tsunamis and hurricanes; they serve as important nurseries for fish and shellfish; they cleanse water of pollutants; and they act as a carbon sink. All those functions, plus the tourism that a healthy coast can encourage, add up to real economic value.

Birds are the conservation magnet that catalyzes collaboration among many partners to conserve coastal wetlands. The work, the vigilance continues. It will, undoubtedly, continue for decades, probably centuries. But amid a drumbeat of discouraging events in the conservation world, it is important to recognize and celebrate some good news.

As professor Piersma puts it: “Now we feel very differently. We don’t believe there will be an extinction. Now we can document and talk about recovery that is very, very positive for the world and for China.”

Wendy Paulson is a nature educator, conservation activist, and chairman of the Bobolink Foundation. She is an education associate of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and former member of its Administrative Board, teaches bird classes in Chicago Public Schools, and leads bird walks in Illinois.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library