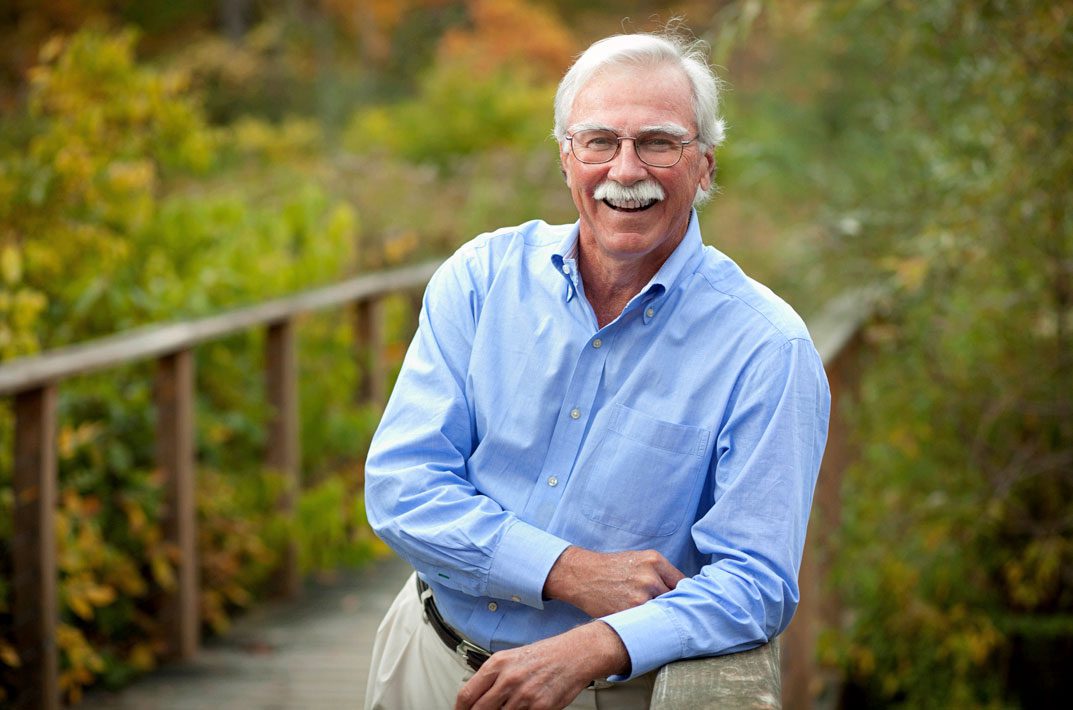

The “Remarkable and Persistently Stimulating” John Fitzpatrick

The Cornell Lab's longtime director prepares to step down, but not step away, from a life's work dedicated to birds. We take a look back at his long and influential career.

By Scott Weidensaul

April 2, 2021

From the Spring 2021 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

So where, I asked Linda Macaulay, do you think the Cornell Lab of Ornithology would be today if she and her colleagues on its administrative board hadn’t hired John Fitzpatrick as the director in 1994?

“Well…we certainly wouldn’t have been able to build the program that we have now,” said Macaulay, now the chair of the Cornell Lab’s board of directors. “I don’t think anybody could have had the vision, but also the nerve, to go out there and try the things that he did. I think we’d just be a small component of Cornell out in the woods.”

Instead, the Lab is a global driver of bird science and conservation, a testament to the 26 years that Fitzpatrick—known by his friends and colleagues simply and universally as Fitz—has been at the helm. Fitz is stepping down from his directorship on June 30. It’s been by any measure the pinnacle of a career spanning half a century, stretching from museum corridors to remote mountaintops in the Andes, from the steamy scrublands of Florida to Sapsucker Woods in Ithaca.

“The fact of who we are today, did I see this in 1994 when I said yes to the job? Nope,” Fitzpatrick said. “But did I see that we could be really great? Yes, but I didn’t know what that meant.”

Each iteration of the Cornell Lab’s development since then, he said, brought new opportunities and wider horizons: “The remarkable and persistently stimulating part of my job is that it has changed every few years.”

“Remarkable and persistently stimulating” is also a pretty good way of describing John Fitzpatrick himself.

“Honestly, if you think about it historically, he’s one of the most important figures in ornithology in the last—you almost need to say the last century, but certainly the last 50 years, which is modern ornithology,” said Melinda Pruett-Jones, the executive director of the American Ornithological Society, which since its days as the American Ornithologists’ Union has been Fitz’s home professional society (he served as the society’s president from 2000 to 2002).

Irby Lovette, the director of Cornell University’s Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program, agrees: “I would say he’s North America’s most prominent ornithologist.

“Fitz has had the biggest and most multifaceted role in ornithology of anyone in his generation, or generations around it, frankly,” Lovette said. “And I think that’s partly because he’s had multiple careers.”

Those overlapping careers include 12 years as a curator with the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago specializing in Neotropical birds, and another six-year career at the Archbold Biological Station in central Florida focused on the conservation of the endangered Florida Scrub-Jay and its habitat.

For the past two-plus decades, he’s been the Louis Agassiz Fuertes Director of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and a Cornell professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, a period that saw the explosive expansion of the Cornell Lab’s size, mission, and global reach.

All along the way, he’s been an outsized voice for bird conservation and for engaging the wider public in the sheer joy of birds. Any one of these facets would have been more than enough for most ornithologists to look back on with satisfaction.

How It All Began

Fitz was born in 1951 in Minnesota in what he describes as “a woodsy, distant suburb of St. Paul” where his parents raised their four boys. Home ill from kindergarten one spring morning, he noticed a dazzling bird.

“It was a male American Redstart, and it was right outside the living room of our house. And my memory was that I said, ‘Is that an oriole?’” Fitz recalled.

He grabbed a Peterson field guide belonging to his father, a casual birder, and matched the bird to its image. Leafing through page after page, he realized, as he now says: “God, look at all these other birds.”

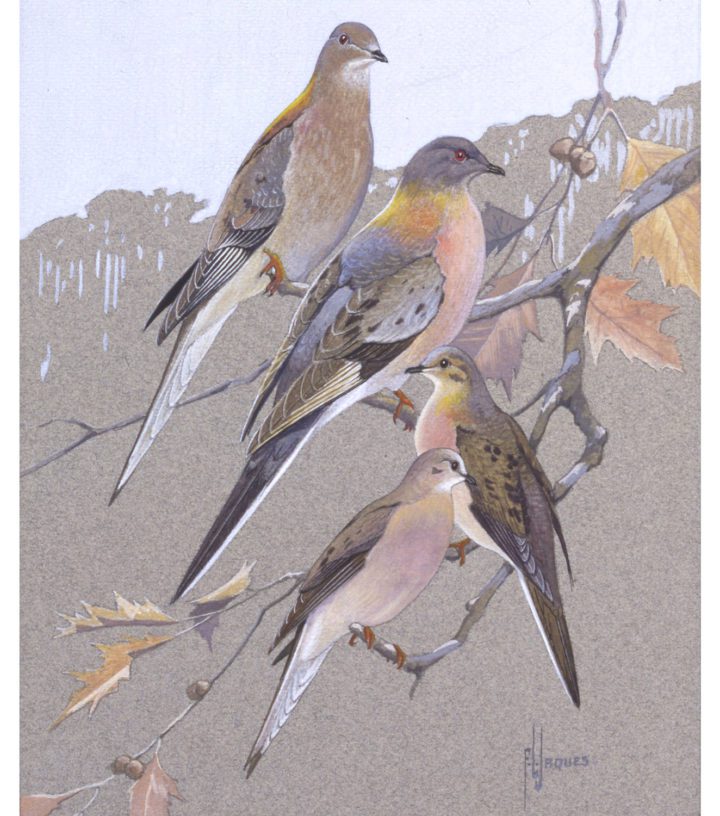

Passenger Pigeons by Francis Lee Jaques, a neighbor and early artistic influence on Fitz. Image courtesy of the Bell Museum.

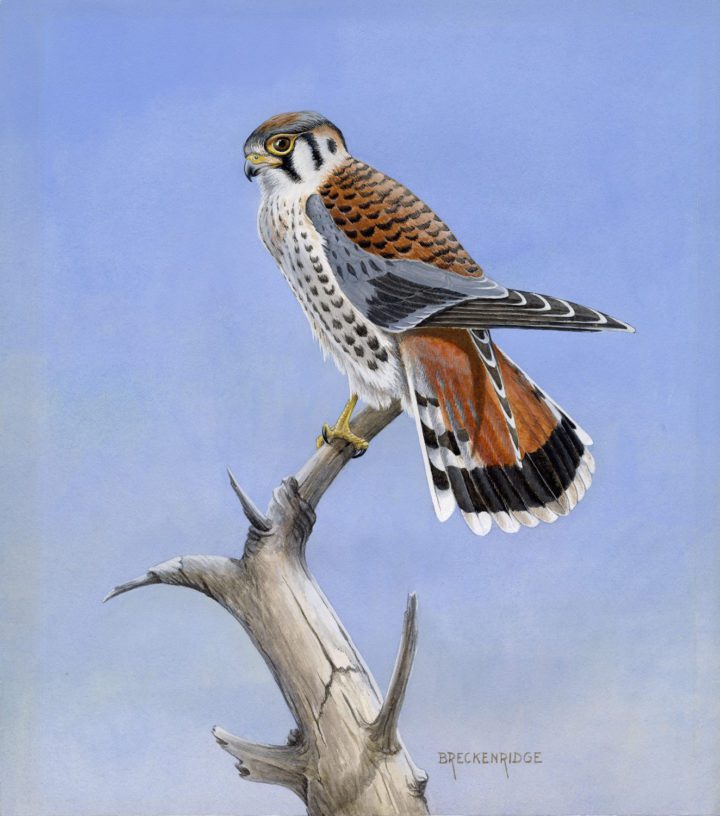

An American Kestrel by Fitz mentor Walter Breckenridge, an ecologist and ornithologist at the University of Minnesota. Image courtesy of the Bell Museum.

The spark had been struck, and it just so happened that young Fitz was growing up in a neighborhood of birders. Nearby lived Francis Lee Jaques, the famed nature artist who in the mid-1950s had recently retired from the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Fitz still refers to him as “the magical Mr. Jaques,” who lit a lifelong interest in art in young John. Other neighbors included Dr. Walter Breckenridge, the prominent ecologist and ornithologist from the University of Minnesota, and avid bird bander Jane Olyphant. By December 1957, having just turned 6, John Fitzpatrick took part in his first Christmas Bird Count. (He’s counted for the CBC every year since.)

Fitz took the bus each day to the St. Paul Academy, where his mother was a teacher. He excelled in class, and during his senior year the headmaster told him he’d likely be accepted at any college he chose. He applied to Harvard, from which both his parents and his older brother had graduated.

With another older brother fighting in Vietnam, Fitz was increasingly involved in the antiwar movement, a factor he suspects led to his rejection by the Harvard alum who interviewed him. The Harvard rejection devastated him, pushing him as close as he says he’s ever been to depression. He decided to take a year off, traveling around the eastern U.S. with a buddy and taking a factory job to earn some money. He reapplied to Harvard in the fall of 1970 and was accepted.

Shortly after arriving at Harvard, Fitz wandered into the Museum of Comparative Zoology, found his way up to the bird division on the fifth floor, and knocked on the first open door he saw, not recognizing the name on the plate. Inside was Ernst Mayr, one of the most important evolutionary thinkers since Darwin. When Mayr, a famously irascible German, learned that the newly arrived freshman knew Lee Jaques (one of Mayr’s old friends from the American Museum), he took the young man under his wing. The MCZ became Fitzpatrick’s home away from home during his time at Harvard, and Mayr became a lifelong friend.

“That museum was a candy store for me that entire four-year period,” Fitz said. But it also set up one of the central through-lines of his career. He got to know Ray Paynter, an expert in Neotropical avian systematics, and at Paynter’s behest began identifying and cataloging all the flycatchers from the scientist’s last trip to Ecuador. Fitz was fascinated, and completed an honors thesis on a complex genus of tody-flycatchers. He was accepted into a graduate program at Berkeley with famed flycatcher expert Ned Johnson—but then, during his last semester at Harvard, he received an unexpected offer that upended everything.

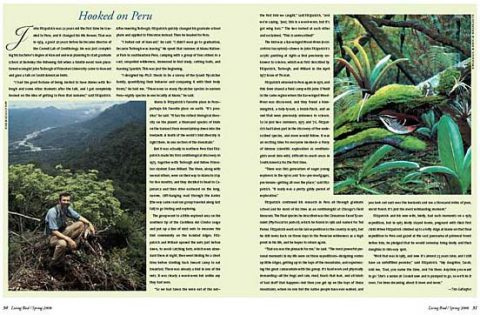

During a student lunch with tropical ecologist John Terborgh, the Princeton professor suggested Fitz spend the entire summer with his field team in one of the most remote parts of Peru, Manú National Park. The young man jumped—canceling Berkeley, shifting to Princeton, and blowing off his Harvard graduation for the jungle.

“I said, ‘Bye, guys, I’m outta here.’” Fitz recalled. “So we spent the entire summer of ’74 in Manú Park, just five of us in a little encampment well up the Manú River called Cocha Cashu. And holy cow, talk about a candy store. It’s the world’s heartland for endemism. It has the world’s largest diversity of birds.”

More on Fitz's Work in Peru

For his PhD dissertation at Princeton, Fitz settled on a wildly ambitious plan to quantify the connection between body form and foraging behavior in all 400 or so species of tyrant flycatchers, a project that took him back to South America repeatedly. In June 1975, he and another Princeton student, Dave Willard, who became one of Fitz’s closest friends, were collecting birds in remote northern Peru. Literally the first bird they caught, their first morning of mist-netting, was an undescribed species of wood-wren with distinctive wing bars—one of several species new to science they found on that and a subsequent trip. Others included a hummingbird, a brush-finch, and—perhaps most importantly to Fitzpatrick—a new pygmy-tyrant in the same group of flycatchers that he had studied at Harvard. They were the first of six or seven new or newly split bird species Fitzpatrick helped describe for science (and, in some cases, illustrate for science; the interest in art that Lee Jaques instilled in him carried over to adulthood).

Fitzpatrick made numerous expeditions into remote parts of Peru in the 1970s and ’80s to study the diverse birdlife of the eastern Andes. Here, Fitzpatrick is at the Paracas Peninsula, a coastal UNESCO World Heritage Site in Peru. Photo courtesy of Dave Willard.

In Peru, Fitzpatrick helped describe many bird species that were new to science. For some species, he was also the first to illustrate them—such as this first look for the scientific world at the Bar-winged Wood-Wren in its habitat.

Fitz’s doctoral program was supposed to last five years, but three years into it in 1977, he was offered a job at the Field Museum in Chicago that was too good to pass up. He wrapped up his PhD within a year, moved to Chicago in 1978, and over the following 12 years rose from assistant curator in the birds division to chair of the museum’s zoology department.

As a Field Museum researcher, he made many expeditions to Peru to collect specimens and study montane tropical birds, exploring questions about the relationships between elevation, habitat, and avian diversity that were sparked by his earlier discoveries of new species. In 1982 Fitz was, as he says, a “wet behind the ears” guest lecturer for the Field Museum when he embarked on his first ecotour, guiding a trip for vacationers to the Galápagos. The tour manager was an “incredibly engaging young lady from Minnesota” named Molly Wyer, Fitz recalled.

A year later they were married, and Molly spent six weeks in Fitz’s field camp in the eastern Andes. Two years later, Fitz headed to Peru again while Molly, expecting their first child, remained at home. Looking out over a pristine mountain wilderness on that trip, he had a realization: “My days of gallivanting months on end in the wilds of the Amazon and the Andes were not going to be practical anymore. …I knew that for the next few years, at least, with babies in the house, I needed to stay in the U.S.”

After that last Field Museum expedition, Fitz—now a family man—transitioned from studying multitudes of species across the vastness of South America to drilling deep into the biology of a single bird renowned for its own close-knit family groups.

Florida’s Archbold Biological Station and Generations of Scrub-Jays

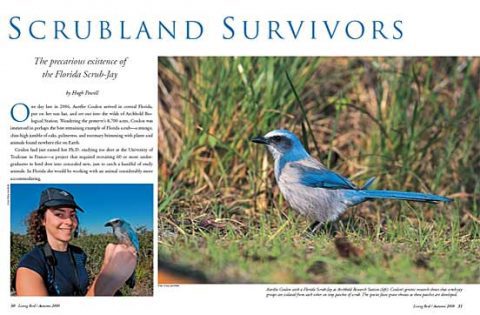

Fitzpatrick’s involvement with the Florida Scrub-Jay—a socially fascinating, behaviorally complex, highly threatened endemic species of the fire-dependent oak-scrub ecosystem of central Florida—dates back to his Harvard undergrad days. In 1972, he took a summer internship under University of South Florida professor Glen Woolfenden at Archbold Biological Station.

Florida Scrub-Jays

Florida Scrub-Jays are unusual birds in many respects. As Woolfenden had documented, they are cooperative breeders, with offspring from previous seasons remaining with their parents to help raise subsequent broods. They are ferociously territorial. And they only occur in oak-scrub habitat, which was being chewed up for citrus plantations, pastures, and housing developments, and overgrown as the fires needed to maintain it were suppressed. Accordingly, scrub-jay numbers plummeted, and the jays were listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1987. Fewer than 4,000 pairs of scrub-jays remain today, scattered across mostly small, isolated habitat patches in Florida.

What started as an internship for Fitz would grow into a defining aspect of his research career. By studying scrub-jays with color bands, Fitzpatrick was able to map, for the first time, the territorial boundaries of about 25 family groups at Archbold. Today, some 85 scrub-jay territories are still meticulously mapped every spring. Fitz has led the labor-intensive fieldwork every year without fail until 2020, when due to the pandemic he had to miss it for the first time in 48 breeding seasons.

With this half-century-long dataset, Fitz and his colleagues at Archbold know the life histories, back as much as 15 or 16 generations, of virtually every bird in this and several other Florida Scrub-Jay populations. In 1985, the AOU presented Woolfenden and Fitzpatrick with the prestigious Brewster Award for “studies that have enriched biology for nearly two decades and promise to provide remarkable information for years to come.” Rarely has a prediction been as fully borne out.

In 1988 Fitzpatrick became the director at Archbold, a position he held for six years. The job wasn’t all scrub-jays; Fitzpatrick established an influential agroecology research program on a nearby, 10,500-acre cattle ranch, for example. And because the Florida scrub ecosystem itself was critically endangered, Fitzpatrick was increasingly involved in, and vocal about, on-the-ground conservation. He was instrumental in the establishment of Lake Wales Ridge National Wildlife Refuge, which stitched together many of the remaining scrub fragments into a protected whole. One tract he saved by literally standing in front of a bulldozer.

“Because of the Endangered Species Act, it was long documented to be illegal to bulldoze scrub that had active scrub-jays in it, without a federal permit,” Fitz recalled. A local company owned land near Archbold, and Fitz invited the company’s owner on a scrub-habitat tour there, complete with perching jays alighting on the company owner’s head. “They had already blitzed 1,600 acres near it. And I was saying, if you can possibly save this last couple-hundred-acre piece, I’m going to show you why it’s so amazing.…So he was saying, well, show me what’s the most important part of this, because we might be able to actually do something here,” Fitz said.

A week later, a bulldozer rolled into that very spot.

“So I stood out there with my camera,” Fitz said. “The guy comes [right] up to me in his bulldozer. And I’m just videoing him. …And he turns the bulldozer around and goes up to the top of the hill, parks it, gets in his truck, and drives away.”

Today that Gould Road scrub tract is still protected by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission.

In a way, the scrub-jay project is the yin to the yang of Fitz’s tropical work. In South America, his perspective was at the landscape level, across broad suites of species. With scrub-jays, he knows the individuals from egg to death and far back in their family pedigrees, focusing on the long-term biology of a single species. The two approaches “expose the full dimensions of the biology and evolution of species,” Fitzpatrick says. “You can move back and forth between the scales of science.”

Today the scrub-jay work is paying off in important new ways, with emerging science now led by former Fitzpatrick grad students like Nancy Chen, an assistant professor at the University of Rochester. Chen is exploring the genetics of scrub-jay populations, thanks to blood samples archived over the decades from 4,000 jays. Her research shows that immigration from small scrub-jay populations is critical to maintaining the genetic diversity and health of even the largest and best-protected populations. It’s not surprising that seeds of long-term research planted decades ago are now ripening, according to fellow scrub-jay researcher Reed Bowman, who has worked with Fitzpatrick at Archbold since 1990 and who now heads the station’s avian ecology lab.

“I always believed Fitz had this long-term plan. He knew something he might do now would bear fruit 20 years from now,” he said.

A New Home: The Cornell Lab of Ornithology

It took Cornell three attempts to hire John Fitzpatrick away from his beloved Archbold.

He’d known about the Lab since 1959, when his parents bought him a birdsong record that Cornell Lab founder Arthur Allen had made. In 1993, he finally visited Cornell when interviewing for the Lab’s first endowed chair for research in bird population studies. At the time, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology was a collection of 14 disparate, aging structures, including leaky trailers and cinderblock buildings (some of which he now likens, only partially in jest, to outhouses). Although Cornell offered him the job, he declined.

When the Lab’s director position opened just a year later, he initially declined to be considered for it. But still Fitz grappled with the question of what the Cornell Lab could become, whether he could help it move beyond its regional-scale influence and fulfill the promise of the Lab’s first forays into citizen science.

As Fitz recalled: “I said to the dean, if you want to build a world-class place that uses birds for a lot of the things they’re powerful for, the minimum size is five professors to lead five labs in five different arenas, and that has to include an evolutionary biologist, which they didn’t have.”

“They really had to work hard to get him,” board chair Linda Macaulay said. “And how lucky are we? We got him.”

With commitments for those changes in hand, Fitzpatrick took the job, and what followed is a story many Living Bird readers will be familiar with—the mushrooming growth of the Cornell Lab from a few dozen employees to today’s institution of some 250 staff. Key to Fitz’s vision was the replacement of those leaky trailers with a proper headquarters.

Following an international competition, Alan Chimacoff—a Cornellian and Princeton professor of architecture—was selected to design a building that would fit aesthetically into Sapsucker Woods, yet accommodate a world-class research institute. In Chimacoff’s words, “We were asked to hide an aircraft carrier along the edge of a beautiful, wooded pond.”

To achieve his vision for a Cornell Lab of Ornithology with varied scientific disciplines and global reach, Fitzpatrick championed the replacement of the Lab’s trailers and run-down buildings with a 21st-century headquarters for a premier research institute. Photo: Cornell Lab archives.

Fitzpatrick at the groundbreaking ceremony for the “new” Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Photo: Cornell Lab archives.

In April 2003, the 90,000-square-foot Imogene Powers Johnson Center for Birds and Biodiversity opened its doors. Legendary Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson delivered remarks at the opening ceremony: “Among its multiple roles as a growing powerhouse for science, education, and public policy, this Lab is a major resource for conservation of biodiversity.”

The spacious new Cornell Lab HQ provided plenty of offices; research and teaching labs; archival space to host the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates and the reels of audio recordings in the Macaulay Library; a Bioacoustics Research Program; and an auditorium—all integrated to house 12 programs in science, conservation, education, and communication. One of those programs, a new addition, was the fruition of one of his big asks during that final job interview with the Cornell dean.

“My commitment was that the Lab of Ornithology start doing evolutionary biology,” Fitz said. He delivered on that commitment by hiring Irby Lovette to lead a new lab within the Lab and seeing to the installation of new technologies for molecular systematics, DNA extraction, and phylogenetic analysis.

For Lovette, the position was more than a dream come true for a newly minted professor: “It added evolutionary biology threads to the Lab’s tapestry of ornithological discovery, while linking us to Cornell’s robust community of scientists who study birds and other organisms. And in the years since, nearly every aspect of avian biology has had a need for the kinds of molecular biology tools and training we can provide to students and to the broader ornithological community.”

Perhaps the most wide-ranging transformation that Fitz presided over was the creation of a digital Cornell Lab available to nearly anyone, anywhere—a shift that reshaped the fields of citizen science, big-data analyses, museum collections, public outreach, and education. So it’s remarkable to think that when he started the job in 1995, Fitzpatrick didn’t use email, nor did the Cornell Lab have a website.

In 1996, the Lab launched its first primitive foray online, with just “our logo and basic stuff,” Fitzpatrick recalled. Over its first weekend, more than 11,000 people visited the website hosted from Sapsucker Woods—a light-bulb moment that spawned a digital revolution.

“The internet was a complete game-changer for citizen science,” Fitz said. Instead of paper forms that had to be mailed and hand-scanned, data could be entered quickly and easily by the person in the field, such as a birder uploading a checklist.

“eBird started as a whimsical coincidence,” said ornithologist Frank Gill, an old friend of Fitzpatrick’s who, in 1996, had just been hired as National Audubon’s chief scientist. They met at Fitz’s childhood home in Minnesota in June of that year to talk over an idea.

“Would there be a way for us to harness bird counts for conservation using the emerging new technologies?” Gill asked. “Fitz was interested in a partnership that tapped [Cornell] University’s computing power. Sensing an opportunity, we shook hands innocently with a Yellow-bellied Flycatcher calling in the background.”

The result of that meeting was BirdSource, a joint Cornell-Audubon digital platform that proved the internet’s value for gathering data from citizen-science efforts like Project FeederWatch and the Great Backyard Bird Count. Under the leadership of Cornell Lab information science director Steve Kelling, eBird emerged from that early partnership in 2002 with backing from a National Science Foundation grant, and the Lab eventually took over operations to grow a promising citizen-science project. But just as Fitz’s vision for the Cornell Lab was gathering momentum, the Lab was rocked by a story that would first astound the bird world, then split it.

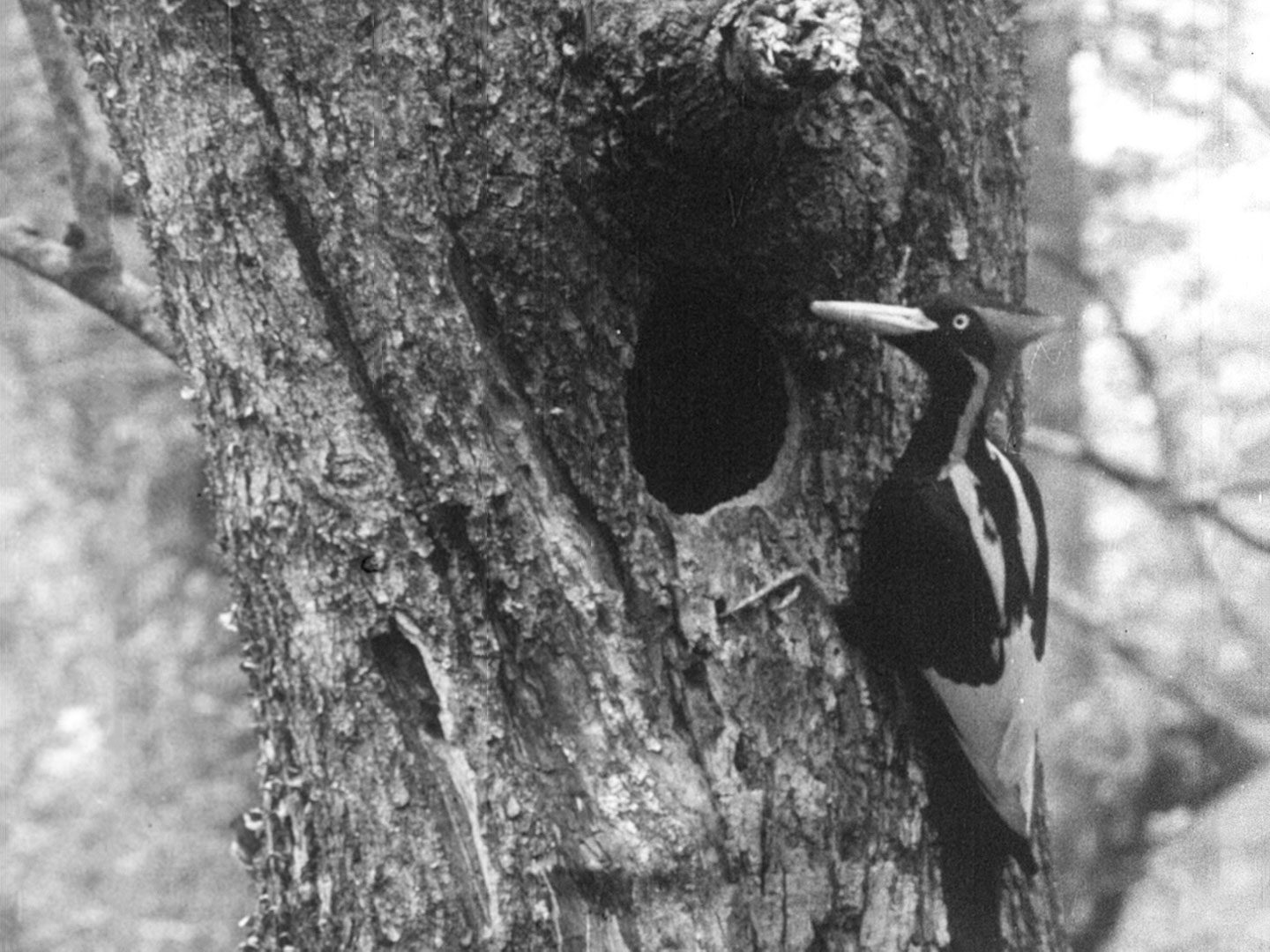

In April 2005 the Cornell Lab, along with The Nature Conservancy, announced that search teams fielded by both organizations had rediscovered the legendary Ivory-billed Woodpecker, long assumed to be extinct, in the swamp forests of Arkansas.

The Cornell Lab’s involvement had started more than a year earlier, on a morning in February 2004 when then–Living Bird editor Tim Gallagher closed the door to Fitz’s office and quietly told him that he and a friend had seen a single ivory-bill on a trip to the Cache River bottomlands.

“I said, ‘Tim, what are the chances that what you saw was not an Ivory-billed Woodpecker?’” Fitzpatrick recalled. “He said, ‘Fitz, it was an ivory-bill. I’m totally, 100% certain of it.’ And I said, ‘Well, Tim, our lives are about to change.’”

And change they did. The Cornell Lab and TNC’s Arkansas chapter mounted a year-long field search in secrecy to enhance the chances of detecting a species known for its wariness around humans. They deployed automatic recording devices and teams of observers, staking out photographers in likely locations and conducting helicopter surveys. The crew collected multiple sighting reports and recordings of what certainly sounded like the ivory-bill’s distinctive double-rap drumming. Most famously, team member David Luneau, an engineering professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, shot a brief, grainy video of a woodpecker taking flight. All of the evidence was laid out in a June 2005 Science article, Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) Persists in Continental North America. (Full disclosure: I was tangentially involved, having been brought in by TNC to write about the discovery for their magazine, and spent a week in the field with the search teams.)

The news was as earth-shattering as any ornithological story, ever, dominating global media for weeks. But the research effort was far from done; in fact, it was just beginning, as coordinated searches by Cornell Lab scientists, academic colleagues, public agencies, and numerous birders ramped up throughout the southeastern United States in the most comprehensive search for Ivory-billed Woodpeckers ever conducted across their range.

“All the way through our time, both before it was public and after, we had one goal—find evidence of breeding woodpeckers,” said Fitzpatrick. “Our job from day one, find the breeding pair because a solo ivory-bill doesn’t do anybody any good.”

But criticisms of the published scientific article began almost immediately, with a rebuttal paper in Science contending the video showed a Pileated Woodpecker. Comments and counter-comments flew back and forth in various journals; friendships ruptured, some never to be repaired. A second claim of ivory-bill rediscovery in 2005, this time by an independent team headed by Auburn University researcher Geoff Hill and working in the Florida Panhandle, only added oxygen to the controversy.

“I’ve said I’ve never felt the obligation to convince anybody that we were right and they’re wrong when they were debating,” said Fitzpatrick. “What I felt was the obligation to make sure all the evidence was presented fairly and accurately, including analyses of the videos frame by frame and of all the other things that we had accumulated as evidence.”

Alas, further extensive searches from 2006 to 2010 did not produce any definitive evidence of a surviving ivory-bill population. The Cornell Lab’s All About Birds species account for the bird today reads: “The Ivory-billed Woodpecker is probably extinct.”

Still, Fitzpatrick says he has no regrets: “What we had evidence for, and I regard the evidence as strong, is that there was one male ivory-bill out there. We also have zero evidence for any breeding birds.

“We ended up fostering and helping to fund the only range-wide systematic search that has ever been conducted for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. And obviously we did it too late.”

And yet, one aspect of the ivory-bill episode that endures is Fitzpatrick’s management style in an institute with differing opinions among fellow scientists.

“I was always skeptical about it,” recalled Lovette of his doubt about the ivory-bill rediscovery. And he freely expressed that doubt, despite being a young professor who had just joined the Cornell Lab a few years earlier. “I was definitely untenured, and Fitz was my boss. But I can tell you at that time that I felt comfortable being skeptical about it openly, even though I was in a vulnerable position.

“It felt like a scientific exploration…I felt totally comfortable voicing my reservations, because it was being treated internally as a hypothesis to be tested.”

Since then, Fitz’s same open-and-honest, try-it-and-see management style (“We’re not afraid to make mistakes and learn from them,” he has often said in meetings) has attracted top scientific and information technology talent to the Cornell Lab. The culture of experimentation and innovation set the Lab on course to become the premier global institution, as the organizational mission states, “to interpret and conserve the earth’s biological diversity through research, education, and citizen science focused on birds.”

In 2010 eBird programmers took the project global, adding the capacity to gather bird-observation data from all over the world. On its 10-year anniversary in 2012, eBird hit the 100 million mark in total species-observations; five years later, it was archiving 100 million bird observations every year.

The big-data storehouse of nearly 70 million birder checklists has become an invaluable tool for supercomputing that’s powering some of the most exciting research in ornithology, from high-resolution visualizations of bird-migration patterns, to a conservation program that identifies the best rice fields in California to flood for migrant shorebirds, to complex spatio-temporal modeling that is documenting the way urban light pollution draws migratory passerines toward big cities at night.

Even after almost two decades, eBird continues to grow more than 25% per year. The eBird database is fast approaching 1 billion total bird observations, with data on virtually all of the world’s roughly 10,700 species of birds.

Lovette thinks eBird will be Fitzpatrick’s most lasting contribution: “He didn’t do it by himself, obviously, but he created the conditions for it to happen and supported it from the very beginning with a lot of vision.

“I think that’s the thing that will have the greatest legacy power, beyond the Cornell Lab of Ornithology writ large.”

A Vision Extends Across the Globe

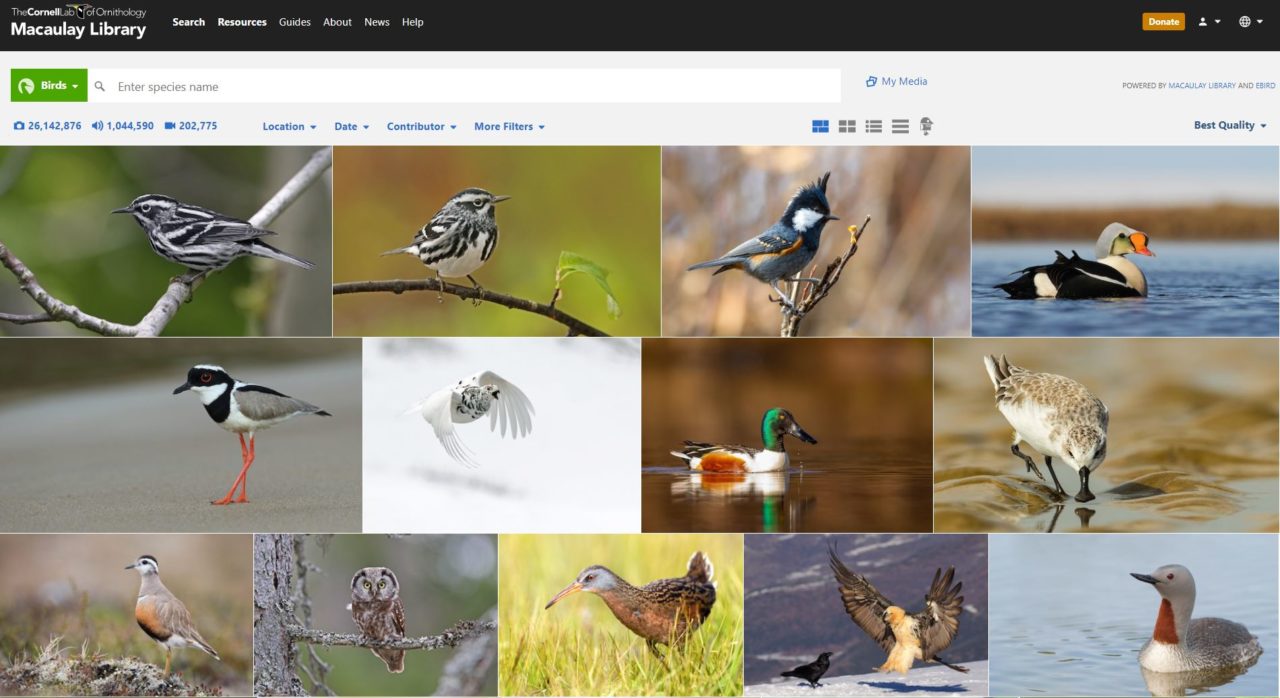

Besides eBird, the Cornell Lab today is a global leader in digital media collections, from the 25 million photos, 200,000 videos, and 1 million audio recordings now available online from the Macaulay Library (the world’s largest archive of natural history media); to the 10,000-plus deeply researched species accounts posted on the Birds of the World online encyclopedia; to the helpful Merlin bird identification app that’s been installed onto user smartphones 5 million times since its launch just six years ago.

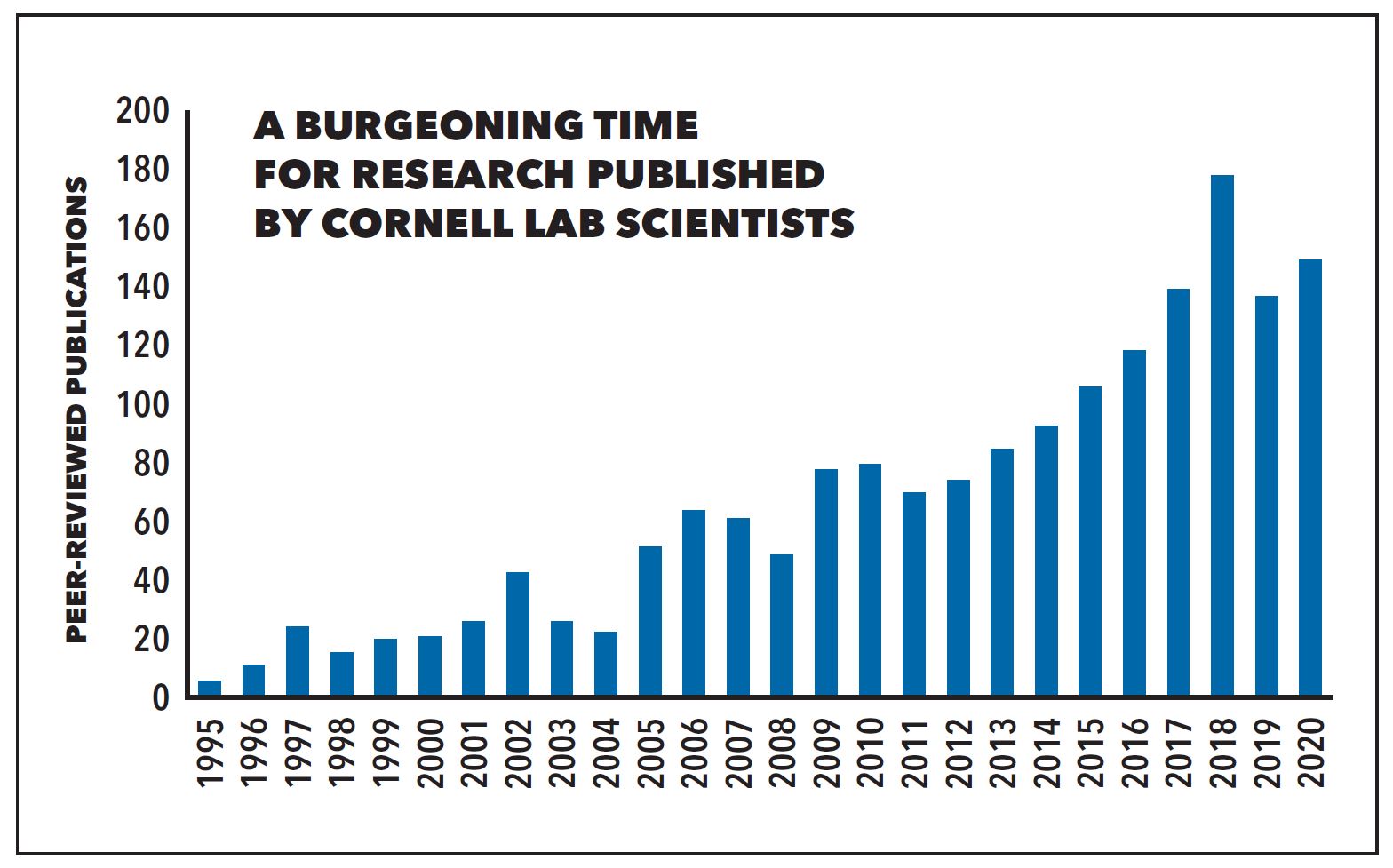

But perhaps what makes Fitz most proud is the Cornell Lab’s growth in scientific output. With more than 30 postdoctoral researchers now in residence, the Lab’s contribution of peer-reviewed research published in scientific journals has grown from fewer than 10 per year in 1995 to nearly 150 in 2020 alone.

One of those papers presented the world with a haunting number—3 billion, the number of breeding birds North America has lost since 1970, according to grim but important research published in the journal Science in October 2019. The paper’s lead author was Ken Rosenberg, a longtime conservation scientist at the Cornell Lab. The news made global headlines—and Fitzpatrick made sure to raise the plight of birds at the highest levels, from a prominent New York Times op-ed (one of many he’s written) to the halls of Congress. In the last few years, Fitz has still been standing in front of metaphorical bulldozers, lending his voice and expertise—honed by real-life experience as an advisor on the federal endangered species recovery teams for Florida Scrub-Jay and Hawaiian Crow—to conservation issues the world over. That voice has never been clearer than during the past four years of the Trump Administration’s assaults on bird conservation, like the gutting of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

“If allowed to take effect in full, these sweeping rollbacks of environmental legislation crafted carefully over the past 100 years will have catastrophic effects on biodiversity,” Fitz wrote in a special policy-analysis section of the Autumn 2020 Living Bird.

He didn’t shy away from wider social controversies, either. In the wake of George Floyd’s death at the hands of police in May 2020, and a racial incident targeting a Black birder in Central Park, Fitzpatrick sent a public letter to the more than 100,000 Cornell Lab members declaring: “Let me be clear: Black Lives Matter. We at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology commit to calling out behaviors and dismantling all traces of policies that promote personal, institutional, or structural racism.”

In the previous few years, Fitz had worked intentionally to broaden the diversity of the Cornell Lab’s administrative board in recruiting new members. Still, at the November 2020 Lab board meeting, Fitz offered what some on the panel saw as a mea culpa.

“It wasn’t a farewell speech, but he was reviewing some of the things he’d done, and of course, diversity was on everyone’s mind,” said Dr. Scott Edwards, a professor of organismal and evolutionary biology at Harvard, the current curator of birds at Fitz’s beloved Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, and one of the relatively few Black scientists at the highest echelons in ornithology. Edwards had joined the Cornell Lab’s board in 2007.

“He was very, I would say, self-critical in the sense that he felt he hadn’t done enough for the Lab in terms of diversity. And I felt bad for him, because he had done so much for the Lab. It’s almost being too hard on oneself to say, ‘Well, I didn’t make as much headway in this particular area as I would have liked.’”

Edwards said that today—post-2020—there “are a new set of problems that frankly the field of ornithology and biology in general simply have not dealt with.” And that’s one of the biggest challenges for the next generation of institutional leaders, he said.

As Fitz wraps up his turn at the helm of the Cornell Lab, he is being recognized for a career dedicated to bird research and conservation. In 2016 he was honored with the American Ornithological Society’s Schreiber Award for extraordinary scientific contributions to the conservation of birds and their habitats. Together with the Brewster Award he received in 1985 for his scrub-jay research, he is one of the few ornithologists to win two professional awards from the AOS. In November 2020, John W. Fitzpatrick was named a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, joining the company of such scientific luminaries as Thomas Edison and W.E.B. DuBois.

The honors are fitting, says AOS director Melinda Pruett-Jones, for an ornithologist who has been “an incredible visionary leader” everywhere he’s worked.

Passing the Baton

And he says he’s not done. Fitzpatrick has plenty of plans for the next phase of his multiple careers—more time to devote to his artwork and watercolors, more time in the field at Archbold taking scrub-jay research into its second half-century (including a new book on the subject), and some continuing involvement at the Cornell Lab. He will remain a full-time Cornell professor while his final cadre of grad students finish their dissertations.

“I’ll be around to help, but I won’t be in the way,” he said, noting his continued involvement with Archbold after his departure there. “I’m a veteran ex-director. I know how to be helpful and stay out of the way.

“I’m very proud of the Lab. We’ve accomplished a lot, and we still are. It’s growing, it’s continuing to explore,” Fitz continued. “I still regard [the Cornell Lab of Ornithology] to this day as an experiment. It’s a strange mix of things …a not-for-profit, mission-driven institute nested inside a world-class research university in a spectacular sylvan setting.

“The world could use a dozen of these places, but by God, I’m damned glad it has at least one.”

Scott Weidensaul is a Pulitzer Prize–nominated nature writer.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library