The People Behind the Birds Named for People: John Cassin

By Elizabeth Serrano

August 28, 2019

From the Winter 2020 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

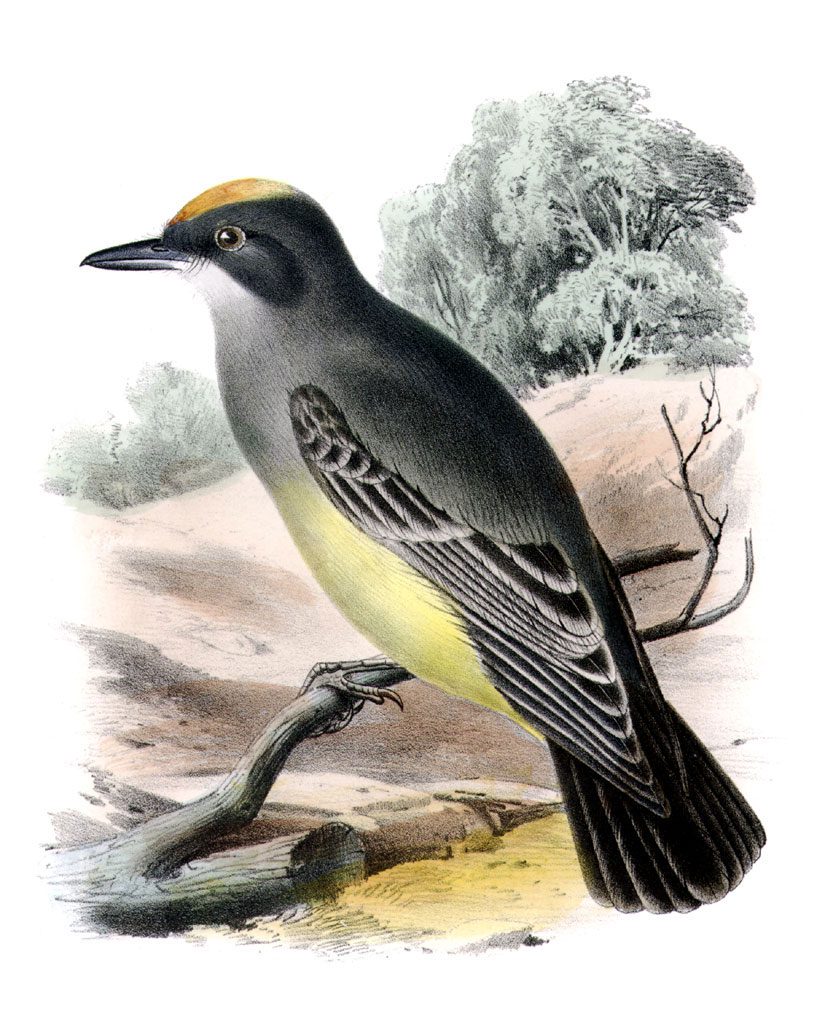

In the dry, open country, of the Southwest lives a lemon-yellow, storm-cloud gray flycatcher known as Cassin’s Kingbird. A prolific songster, it’s a species as prominent as the ornithologist it was named after, John Cassin. Though his name isn’t as familiar today as Audubon’s or Peterson’s, Cassin was a major figure of nineteenth-century ornithology. With five American birds named after him (and four more from elsewhere in the world)—Cassin is matched only by Alexander Wilson as a namesake for North American species.

Born in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, in 1813, Cassin was something of a prodigy—at the age of 17 he was drawing flowers in remarkable detail, and even identifying plant species that were missing from his botany textbook. Eventually, he combined his naturalist’s eye with the meticulous attention of a scientist, bringing a new level of rigor and scientific method to American ornithology.

At the young age of 20, Cassin co-created the Delaware County Institute of Science in his hometown, and then moved to the City of Brotherly Love in 1834. There he joined the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, first as honorary curator but eventually serving as both vice president and corresponding secretary during his 26 years there.

There was no better place for an American naturalist with a budding interest in taxonomy to be. Known today as the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, it is the oldest natural history museum in the U.S. At the time, the Academy hosted the largest collection of bird skins in existence—some 25,000—including specimens from Australia, India, and Africa. Over his career, Cassin described 193 new bird species. African birds were a particular fascination, and today four African species, including a honeyguide and a hawk-eagle, are named for him.

Ornithology was not yet a full-time paying job in the 1830s, so to support his wife and two children Cassin managed a lithographing establishment where many of his works were printed. “It is hard work, this studying foreign birds,” he wrote. “It would do very well was there no arrangement to be made for ensuring the supply of bread and butter.” Nonetheless he was prolific: his output included 3 books, some 15 articles, and reports of U.S. government expeditions abroad, some of which he accompanied.

John Cassin, 1813-1869. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Black-headed Bee-eater and Blue-headed Bee-eater by Otto Koehler, from an 1860 article by John Cassin in the Journal of the Natural Academy of Sciences of Philadelphia. Page scan by Elizabeth Serrano from a volume in the Kroch Library, Cornell University.

Even while running a business, Cassin took it upon himself to become the most knowledgeable ornithologist of the mid-nineteenth century, carrying on the work of luminaries Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon, 47 and 28 years his senior respectively. Many of the specimens Cassin worked with were originally collected by Wilson. Whereas his predecessors sought to describe and illustrate North America’s birds one species at a time, Cassin took a more systematic view. Aided by his encyclopedic knowledge of the Academy’s holdings, Cassin examined the ways in which birds are related to each other.

Black-capped Chickadee by George G. White, from Cassin's 1862 book Illustrations of the Birds of California, Texas, Oregon, British and Russian America. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Kirtland's Warbler by William E. Hitchcock, from Cassin's 1862 book Illustrations of the Birds of California, Texas, Oregon, British and Russian America. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Cassin believed a scientist needed to go beyond just field observation and apply scientific rigor to their work. “It is by no means desirable to be exclusively a naturalist of the woods,” Cassin wrote. “There must be a combination of theoretical and practical acquirements.”

Related Stories

Cassin joined the Union Army during the Civil War, and served time as a prisoner of the Confederates. His health failed shortly afterward, but it was likely his time in museums, not prisons, that did him in. At the time, specimens were preserved with arsenic, and Cassin noted the toll it took, writing that his work meant “mortgaging myself by perpetual lease to arsenic and liver complaint.” He died in January 1869, at the age of 56. His death record lists “remittent fever” as the cause.

Cassin’s determination and insight inspired the ornithologists that followed. George Lawrence, who had conducted surveys in the Pacific for Cassin, named a kingbird for him. William Gambel named a sooty, tennis-ball-sized auk Cassin’s Auklet. A red finch of the western mountains was named Cassin’s Finch by Spencer Fullerton Baird, the first curator of the Smithsonian Institution. Samuel Washington Woodhouse described the Cassin’s Sparrow, and Hungarian-born explorer John Xantus collected the first Cassin’s Vireo. (If these ornithologists’ names sound familiar, it’s because of birds like Gambel’s Quail, Lawrence’s Goldfinch, Baird’s Sandpiper, Woodhouse’s Scrub-Jay, and Xantus’s Hummingbird.)

A century and a half after his death, birds as different as seabirds and sparrows still bear Cassin’s name, as a reminder of his critical role in shaping American ornithology.

Elliot Coues paid tribute to Cassin’s legacy on hearing of his passing, writing to a colleague, “…many as are our American ornithologists—high as some stand in American ornithology—there is none left in all our land who can lift up the mantle that has fallen from his shoulders.”

Elizabeth Serrano ’20 is an Animal Science major at Cornell University. Her work on this story was made possible by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Science Communication Fund, with support from Jay Branegan (Cornell ’72) and Stefania Pittaluga.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library