The Beauty and Biology of Egg Color

By Pat Leonard

One of the key functions of egg pigmentation is camouflage. These Little Ringed Plover eggs blend in with their stony surroundings. Photo by Michel Poinsignon/Minden Pictures. June 12, 2017From the Summer 2017 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Fish do it. Frogs do it. Even insects lay eggs with color. But birds do it best.

Only birds produce eggs in such a wide range of eye-pleasing shades and intricate patterns on the hard surface of their eggs.

Like gems in a jeweler’s window, they vary in base color, how shiny they are, and whether they are covered in Sanskrit-like scrawls or patterns of spots.

But, how does the color get there? What is it made of? Does it benefit the embryo? And, why are some eggs plain white?

Egg pigmentation is surprisingly complex.

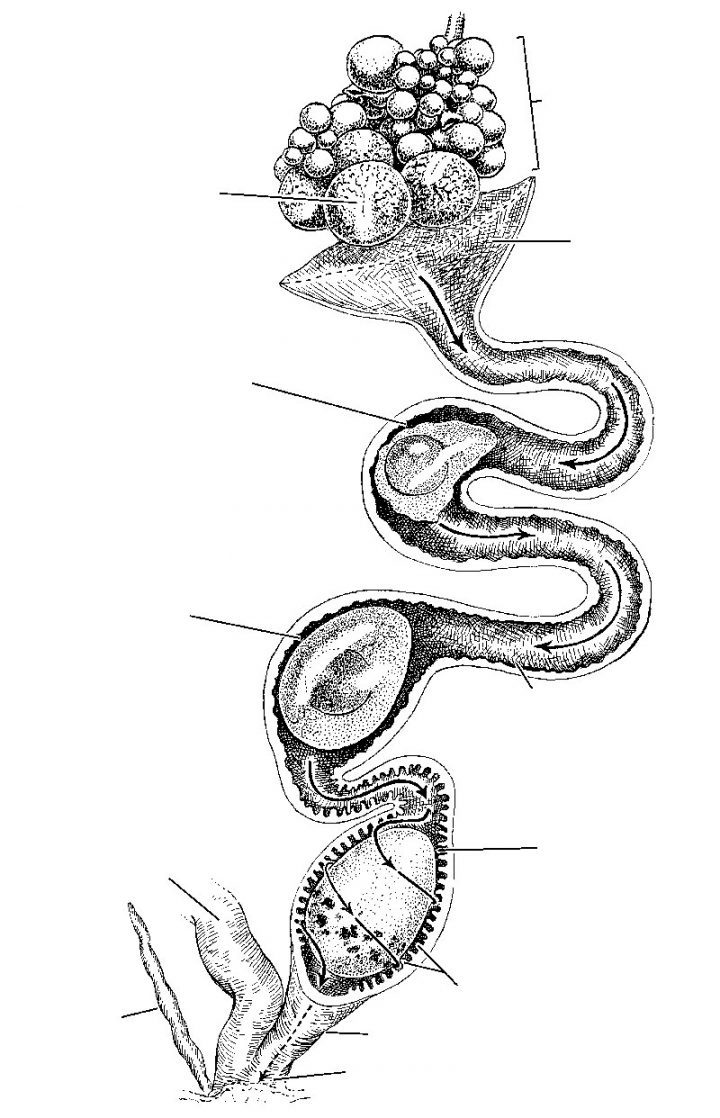

Building the Egg

An egg’s story begins in a female bird’s single ovary. When an ovum is released into the oviduct and fertilized, it is just a protein-packed yolk. The albumen—the gelatinous egg white—is added next. The blobby mass then gets plumped up with water and encased in soft, stretchy membrane layers. The first globs of the calcium carbonate shell are then deposited on the exterior, with the mineral squirting from special cells lining the shell gland (uterus). Pigmentation, if any, comes next, with an overall protein coating added before the egg is laid. It takes about 24 hours to build a single egg.

In his book, The Most Perfect Thing: Inside (and Outside) a Bird’s Egg, University of Sheffield zoologist Tim Birkhead compares the pigmentation process to an array of “paint guns.” Each gun is genetically programmed to fire at a certain time so that the signature background color and spotting of a species’ eggs is produced.

“Examination of birds’ oviducts at the time the color is placed on the egg suggests that the color is produced and released over a very short time frame,” Birkhead says, “usually in the last few hours before the egg is laid, and that makes it very hard to study.”

Coatings of Many Colors

Despite the variety of egg colors and patterns, the palette is surprisingly small. Egg pigments are versatile substances made of complex molecules synthesized in a bird’s shell gland. Only two pigments are at work. Protoporphyrin produces reddish-brown colors. Biliverdin produces shades of blue and green. More of one pigment, less of the other, and the egg gets a different background color, spots of a different color, or a combination of both.

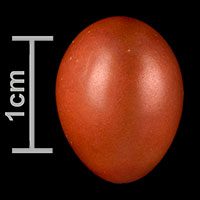

For example, the intense brick-red of Cetti’s Warbler eggs comes from protoporphyrin alone. All birds are likely to have the basic genetic machinery to produce the two pigments, even if they use only one of them, or use none at all and produce plain white eggs.

A female bird needs to take in extra calcium in order to produce the eggshell, and her diet can also be a factor in the production of the type and quantity of pigments. Paler-than-normal colors may be the by-product of a bird’s poor diet or an immune system challenged by disease. Even in the same clutch, each egg will be pigmented somewhat differently.

“Birds that lay multiple eggs, such as thrushes and flycatchers, seem to change the color of their eggs throughout the laying cycle as if they were running out of the pigments,” says Cornell PhD Mark Hauber, who wrote The Book of Eggs and studies them at Hunter College of the City University of New York.

And over time, eggshell colors and patterns within a species can also change. Mark Hauber feels bird-egg pigmentation may have evolved and disappeared multiple times and says it seems to be a rather “pliable” trait.

“With just two mutations, a Japanese Quail, which lays beige eggs with brown speckles, can start laying plain blue eggs,” Hauber says. “So, it’s really easy to genetically regulate metabolic pathways to start laying different colored eggs.”

The deep history of egg color remains unknown. Some scientists think the dinosaur ancestors of birds produced only white eggs, as reptiles still do today, and that pigmentation came later. Others suggest dinosaur eggs could have been blue.

Finishing Touches

Though all bird eggs are made of calcium carbonate, the underlying shell structure differs among species. The outer coating of the shell—the cuticle—can also make a difference in the finish of the egg. For example, the glossy eggs of the tinamou family—from the reddish-purple egg of the Red-winged Tinamou to the emerald green of the Elegant Crested-Tinamou—give off a high-wattage shine.

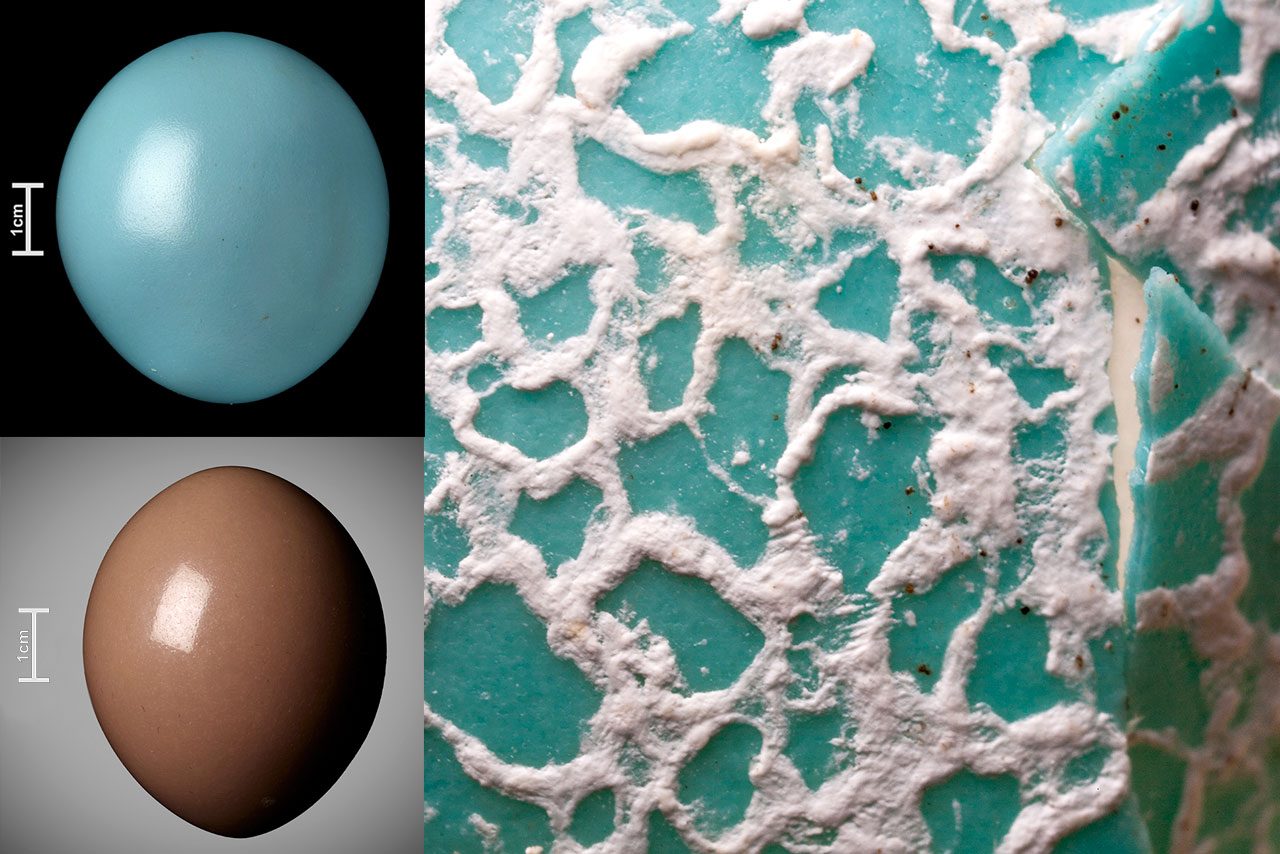

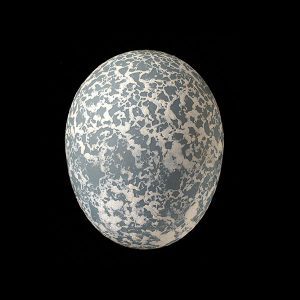

The Guira Cuckoo’s egg is a wonder. Before the egg is laid, the base color is covered with a chalky layer of flaky calcium carbonate called vaterite that is structurally different from the eggshell itself. During incubation, the outer layer flakes off in patches, revealing a smoky gray or turquoise underneath in intricate patterns, rather like an artist’s scratchboard. It’s one of Hauber’s favorite eggs.

“It’s like having a little jewel in your hand,” he says. “The eggs of some species of anis are like this, too. Among communal nesters that chalky layer might act as a bumper to prevent damage when the eggs knock against each other. We’re trying to figure out if that flaky white material has any pigments in it.”

Pigmentation as a Parental Cue

Some egg pigment functions are well established by science. Camouflage is one. Many species that nest on the ground produce speckled or streaked eggs that blend in well with their surroundings and befuddle predators. Look at the eggs of any shorebird and you’ll find nearly all of them are speckled to blend in among rocks, pebbles, and sand to foil egg-stealing snakes, lizards, squirrels, and raptors.

As a general rule, birds that lay all-white eggs tend to be cavity-nesting species, such as owls and woodpeckers. Their eggs are already hidden from view so there’s no reason to produce pigmented eggs. There’s also a theory that white eggs show up better in a dark cavity.

But, there are exceptions. Even though camouflage makes sense for most species that lay their eggs in nests on the ground, some ground-nesting species—such as tinamous and nightjars—produce bright-colored, conspicuous eggs, which means other forces are at work. It helps to understand a species’ life history.

Several Great Tinamou females may lay their shiny, unspeckled turquoise eggs on contrasting brown leaf litter in the same depression or scrape on the ground without building an actual nest of sticks or mud. Cornell PhD Patricia Brennan, now at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, studied these birds in Costa Rica, noting that the eggs are not camouflaged or well concealed despite the threat of predation. Brennan suggests that egg color is a signal to other females, drawing their attention to the nest and promoting synchronous laying. The benefit to the birds is that, even if a predator does strike, it cannot eat all the eggs and those of any one individual stand a better chance of surviving.

Scientists say some species get away with laying conspicuous eggs because the parents sit tightly on the nest, with both male and female sharing round-the-clock incubation duty so the eggs are almost never exposed to view. In fact, another novel, though disputed, explanation for brightly colored, conspicuous eggs is called the “blackmail theory.” Bucknell University’s Daniel Hanley has theorized that, because conspicuous eggs are at greater risk of predation, females may lay them to blackmail their mate into more active participation at the nest. If the male wants the showy eggs to stay covered up and protected, he must take turns incubating on the nest himself or bring food to the female so she can stay on the nest.

Pigmentation as Identifier

Some eggs are pigmented and patterned in defense against brood parasitism, which is when one species lays its eggs in the nest of another species as a ploy to get host parents to raise its young. Brown-headed Cowbirds are among the most famous nest parasites in North America, inducing Red-winged Blackbirds and other species into caring for cowbird nestlings.

Evolutionary biologist Claire Spottiswoode from the University of Cambridge says egg speckling can be a strategy to help parents differentiate their own eggs from those laid by an intruder. But it doesn’t always work.

“It seems likely that natural selection seized on egg speckling and elaborated upon it to generate the complex egg signatures of identity that we see in host birds,” explains Spottiswoode. “But those patterns can also be mimicked to some degree by their parasites.”

Spottiswoode’s studies of a species called the Parasitic Weaver in Zambia attempt to measure the competing pressures on both host and parasite in what she terms a “coevolutionary arms race.” The battle between host and parasite often plays out in alternating egg pigmentation changes. Over time, the host species alters the look of its eggs, which the parasite then tries to mimic closely enough so that its eggs are not rejected. These changes happen surprisingly quickly—even within a few decades.

“What we’ve seen in Zambia is primarily a shift in the frequency of existing colors, given that the range of egg pigments is actually quite limited,” Spottiswoode says. “We know from other systems that natural selection can sometimes be startlingly effective in generating evolutionary change and that eons aren’t always needed!”

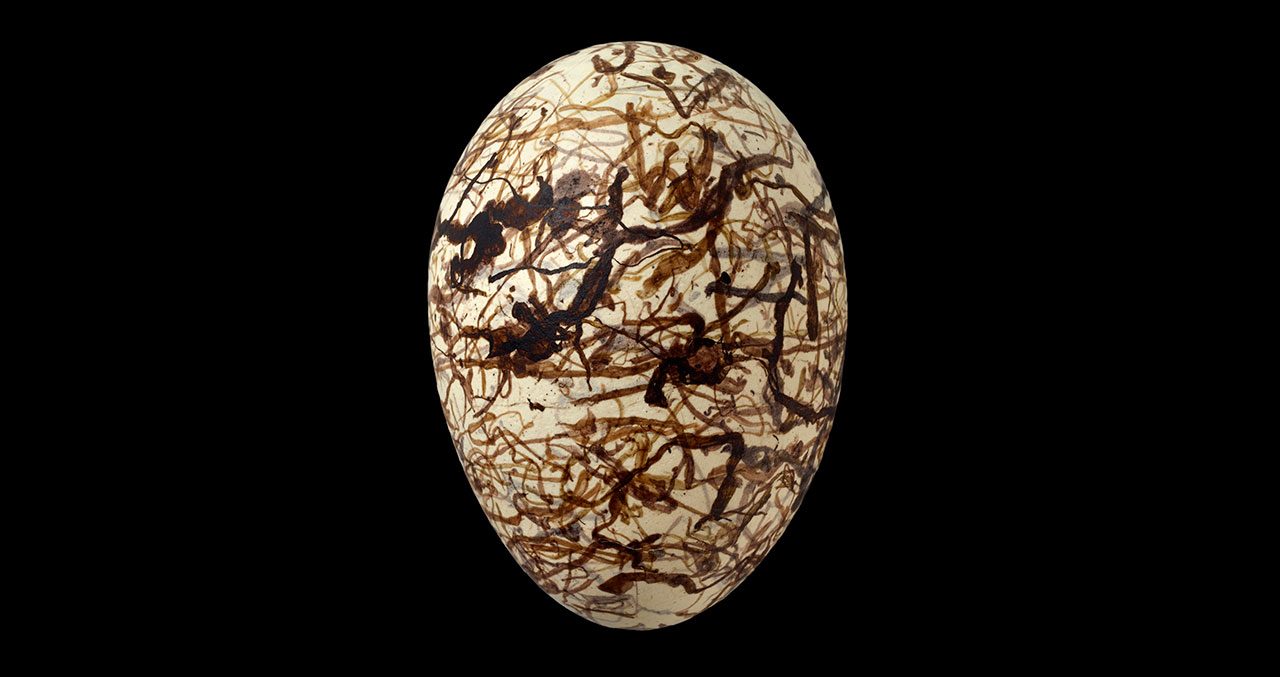

But again, nature throws in a few wrinkles that are hard to explain. For example, the Tawny-flanked Prinia produces fine squiggles on its eggs that are impossible for Parasitic Weavers to replicate, yet the weaver often successfully parasitizes prinia nests.

“This is a real mystery to me because having apparently evolved a perfect signature, the prinias seem not to use it,” Spottiswoode says. “Unsquiggled eggs are clearly accepted at least sometimes, otherwise this strain of parasites would be defeated and have died out.”

Pigmentation as Sun Block

Pigment may also have a specific function related to sunlight. David Lahti, at Queens College of the City University of New York, and Cornell PhD Dan Ardia at Franklin and Marshall College, studied specimens of Village Weaver eggs from Africa, which naturally vary from white to blue-green. Their theory is that egg color can represent a balancing act between two impacts of light—one good, one bad.

“There must be a trade-off between embryo protection from damaging UV rays, what we call the parasol effect, and the cost of additional pigmentation causing overheating, the dark-car effect,” Ardia explains. “We found good evidence that DNA-damaging UV light transmits more easily through the eggshell when there isn’t much pigmentation. But heavily pigmented eggs do heat up faster, which is also very dangerous for the embryo.”

Lahti plans further studies to explore whether light levels have an influence on egg colors in other species.

Multiple studies have examined egg color in relation to the embryo’s growth. Some theories suggest that variable amounts of pigment at each end of an egg allow differing levels of light to filter through, which may help the embryo develop a sense of direction and also cue the development of specific structures in its body. Another idea is that darker or lighter colors among eggs in the same clutch might play a role in whether the eggs hatch all at once or in sequence.

Some researchers think the intensity of an egg’s color may say something about the health of the female bird, important information for males who may be deciding how much time to invest in incubating eggs and bringing food to the nest.

“There are many competing hypotheses to explain egg coloration and they’re not all mutually exclusive,” Ardia points out. “Pigment function is almost surely a complicated combination of factors depending on the idiosyncrasies of each species.”

More Questions

Despite the research already done on the colors and patterns of bird eggs, plenty of questions remain.

For example, what do the birds see when they look at the eggs? Mark Hauber’s lab is investigating how some birds see more of the light spectrum than humans do.

“Some birds, such as most galliforms or ducks, don’t see ultraviolet light,” Hauber explains. “But some gulls, hummingbirds, most songbirds, and even ostriches do see UV light and might be picking up more information from egg colors and patterns than we can see.”

Lahti is fascinated by instances in which some birds lay only blue eggs, but other individuals of the same species lay only white eggs, as is the case with Eastern Bluebirds.

“I don’t know what’s going on there,” he says. “Bluebirds are in the Turdidae family in which nearly all species have blue eggs. But bluebirds may be making an evolutionary transition to white eggs, which would be expected since they nest in cavities or nest boxes.”

“One persistent mystery is why many open-nesters like the American Robin lay blue eggs. Is this camouflage? Does it signal, as one study strongly suggests, female quality? We don’t know,” muses Birkhead. “Among other species, we also don’t know how those exquisite pencil-like scribbles are produced on some eggs.”

Whether scientists are trying to unlock their secrets, or simply enjoy their beauty, bird eggs are one of nature’s little miracles—a fragile, self-contained, breathable package evolved to protect the tender bud of life unfolding within.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library