Sympathy for a “Little Devil,” the Black-capped Petrel of the Caribbean

By Hugh Powell

October 15, 2012

On a cold January night in 2008, on a mountaintop in Haiti, eerie cries filled the air. Clouds obstructed the moon and heavy shapes passed invisibly above the forest’s twisted canopy. Only a low moaning gave away the birds’ presence, and hinted at one of their colloquial names,diablotín, or “little devil.”

To James Goetz the birds were Black-capped Petrels—an endangered species that breeds in the Caribbean and forages in Gulf Stream waters off the United States. Fewer than 2,000 breeding pairs are thought to remain, although the bird’s secretive habits make even the most basic population estimates hard to come by.

“The birds are phantoms, basically,” said Goetz, who funded his 2008 survey on a shoestring, from his own pocket. “No one had really surveyed for them in Haiti in 20 years,” he said, “so I flew a friend down who could speak Creole, teamed up with a couple of Haitian field assistants I knew, and we just got the ball rolling.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service funded follow-up expeditions, which Goetz, now a Ph.D. student at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, tackled with the help of collaborators from the American Bird Conservancy and Hispaniolan nonprofits Grupo Jaragua, Société Audubon Haiti, and Fondation Seguin. The news has been getting better since then, and 2012 has been a watershed year, with new technologies such as motion-activated cameras and radar surveys yielding more petrels and nests than scientists have ever found before.

Black-capped Petrels are easy enough to identify at sea—the crisp, gray-and-white birds are so sharply marked they’ve been called a “flying field mark.” Finding their nests is another matter. They dig burrows into steep limestone cliffs, and visit them only after dark. Until the application of radar this year, surveying for the birds meant listening for calls and then guessing how many petrels were making them. Actually finding the nests had to wait for daylight, when field researchers would comb steep hillsides or rappel down cliff faces to search for burrows.

Searches in the past decade had turned up only a handful of nests. A breakthrough came in 2011, when researchers installed a motion-activated camera at a nest entrance to record adults making feeding visits—the first real opportunity to learn details about the birds’ life on land.

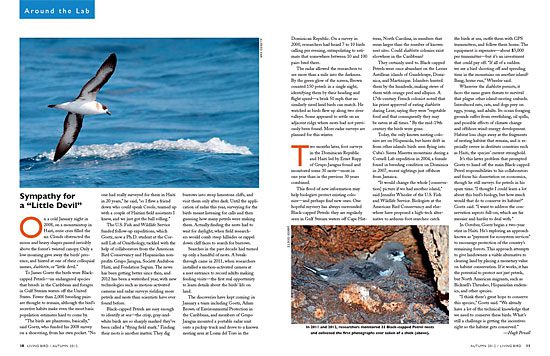

The discoveries have kept coming: in January a team including Goetz, Adam Brown of Environmental Protection in the Caribbean, and members of Grupo Jaragua mounted a portable radar unit onto a pickup truck and drove to a known nesting area at Loma del Toro in the Dominican Republic. On a survey in 2000, researchers had heard 7 to 10 birds calling per evening, extrapolating to estimate that somewhere between 10 and 100 pairs bred there.

The radar allowed the researchers to see more than a mile into the darkness. By the green glow of the screen, Brown counted 150 petrels in a single night, identifying them by their heading and flight speed—a brisk 50 mph that no similarly sized land birds can match. He watched as birds flew up along two river valleys. Some appeared to settle on an adjacent ridge where nests had not previously been found. More radar surveys are planned for this winter.

Two months later, foot surveys in the Dominican Republic and Haiti led by Ernst Rupp of Grupo Jaragua found and monitored some 30 nests—more in one year than in the previous 30 years combined.

This flood of new information may help biologists protect existing colonies—and perhaps find new ones. One hopeful mystery has always surrounded Black-capped Petrels: they are regularly seen in Gulf Stream waters off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, in numbers that seem larger than the number of known nest sites. Could diablotín colonies exist elsewhere in the Caribbean? They certainly used to. Black-capped Petrels were once abundant on the Lesser Antillean islands of Guadeloupe, Dominica, and Martinique. Islanders hunted them by the hundreds, making stews of them with orange peel and allspice. A 17th-century French colonist noted that his priest approved of eating diablotín during Lent, saying they were “vegetable food and that consequently they may be eaten at all times.” By the mid-19th century the birds were gone.

Today, the only known nesting colonies are on Hispaniola, but hints drift in from other islands: birds seen flying into Cuba’s Sierra Maestra mountains during a Cornell Lab expedition in 2004, a female found in breeding condition on Dominica in 2007, recent sightings just offshore from Jamaica. “It would change the whole [conservation] picture if we had another island,” said Jennifer Wheeler of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Biologists at the American Bird Conservancy and elsewhere have proposed a high-tech alternative to arduous foot searches: catch the birds at sea, outfit them with GPS transmitters, and follow them home. The equipment is expensive—about $3,000 per transmitter—but it’s an investment that could pay off. “If all of a sudden we see a bird shooting off and spending time in the mountains on another island? Bang, home run,” Wheeler said.

Wherever the diablotín persists, it faces the same grave threats to survival that plague other island-nesting seabirds. Introduced rats, cats, and dogs prey on eggs, young, and adults. Its ocean foraging grounds suffer from overfishing, oil spills, and possible effects of climate change and offshore wind-energy development. Habitat loss chips away at the fragments of nesting habitat that remain, and is especially severe in destitute countries such as Haiti, the species’ current stronghold. It’s this latter problem that prompted Goetz to hand off the main Black-capped Petrel responsibilities to his collaborators and focus his dissertation on economics, though he still surveys for petrels in his spare time. “I thought I could learn a lot about this bird’s biology, but how much would that do to conserve its habitat?” Goetz said. “I want to address the conservation aspects full-on, which are far messier and harder to deal with.”

In October, Goetz began a two-year stint in Haiti. He’s exploring an approach known as “payment for ecosystem services” to encourage protection of the country’s remaining forests. This approach attempts to give landowners a viable alternative to clearing land by placing a monetary value on habitat conservation. If it works, it has the potential to protect not just petrels, but North American migrants, such as Bicknell’s Thrushes, Hispaniolan endemics, and other species. “I think there’s great hope to conserve this species,” Goetz said. “We already have a lot of the technical knowledge that we need to conserve these birds. What’s still a challenge is getting the incentives right so the habitat gets conserved.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library