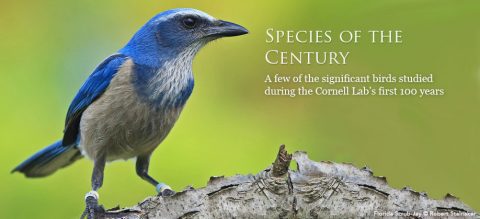

Species of the Century

By Gustave Axelson

From the Winter 2015 issue of Living Bird magazine.

January 15, 2015

From its founding, the Cornell Lab has focused on revealing the mysteries of bird biology and behavior through scientific inquiry. What began as discoveries and revelations about individual species grew into an appreciation for the role of birds within their broader ecosystems and the importance of those species to the larger world. In recent times the Cornell Lab has been building on another dimension—using science to guide conservation action that saves bird populations and protects places. Now as it all comes together—the science of species, of processes and places, of change—we can look back at the birds that brought us here.

A few of the significant birds studied during the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s first 100 years:

Ivory-Billed Woodpecker, Campephilus principalis In 1935, Allen and Kellogg lead an ornithological expedition to document the last known breeding populations of Ivory-billed Woodpecker in Louisiana. Using Movietone recording equipment, Kellogg gathers audio recordings that would be used 70 years later in a modern search for ivory-bills. Despite a few tantalizing brief sightings, the new expedition ends with the conclusion that it is unlikely that recoverable populations of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers still exist in the United States. The 1935 recordings are still the only confirmed recordings of the voices of ivory-bills.

Golden-Winged Warbler, Vermivora chrysoptera In 2012, the Cornell Lab and partners produce one of the most thorough research-backed strategies for a single bird species in steep decline: the Golden-winged Warbler Conservation Plan. The plan rolls over a decade of survey data, genetic research, and habitat studies into a blueprint for creating an additional 1 million acres of Golden-winged Warbler habitat over the next 50 years, enough to grow the global population by 50 percent.

Florida Scrub-Jay, Aphelocoma coerulescens Two ornithologists—Cornell graduate Glen Woolfenden and a young summer intern named John W. Fitzpatrick (who would go on to become the Cornell Lab’s director)—team up in 1972 to investigate the biology of the Florida Scrub-Jay. The work continues for 35 years, one of the longest-running studies of any wild living thing. Together, Woolfenden and Fitzpatrick discover the critical role that wildfire plays in renewing the endangered scrub-jay’s habitat. Photo by Tim Gallagher.

Ruffed Grouse, Bonasa umbellus Cornell Lab of Ornithology professors Arthur Allen and Peter Paul Kellogg publish research in 1932 on the first investigation of bird behavior using new motion-picture technology. Their big find—Ruffed Grouse beat their wings against the air, not their breasts or the logs they perch upon, to produce their drumming sound. Photo by Marie Read.

Peregrine Falcon, Falco peregrinus In 1970, Tom Cade begins an ambitious captive-breeding effort for endangered Peregrine Falcons in a barn at Sapsucker Woods. After Cade founds The Peregrine Fund, the species rebounds from extirpation in the eastern United States over the next couple of decades as more than 5,000 falcons are released into the wild in 37 states and Canada. In 1999, the Peregrine Falcon is removed from the Endangered Species list, with thousands of breeding pairs in North America. Photo by Nick Dunlop.

Spoon-Billed Sandpiper, Calidris pygmaea In 2011, the Cornell Lab sends Gerrit Vyn on an expedition to Chukotka along Russia’s Bering Sea coast to gather HD video and high-quality sound recordings of the critically endangered Spoon-billed Sandpiper, before the final 100 nesting pairs vanish from the earth. The visuals of these apple-sized, russet shorebirds courting and breeding on the Russian tundra are a powerful tool for conservation groups working to protect shorebirds and their habitat all along the East-Asian Australasian Flyway. Photo by Gerrit Vyn.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library